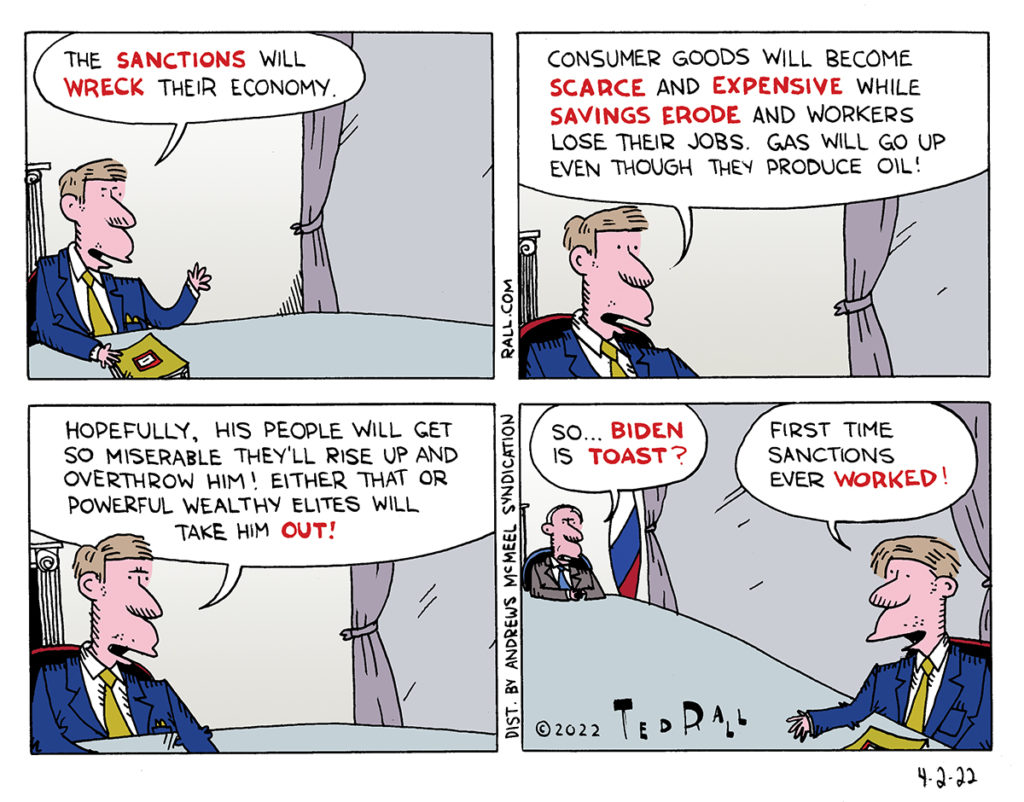

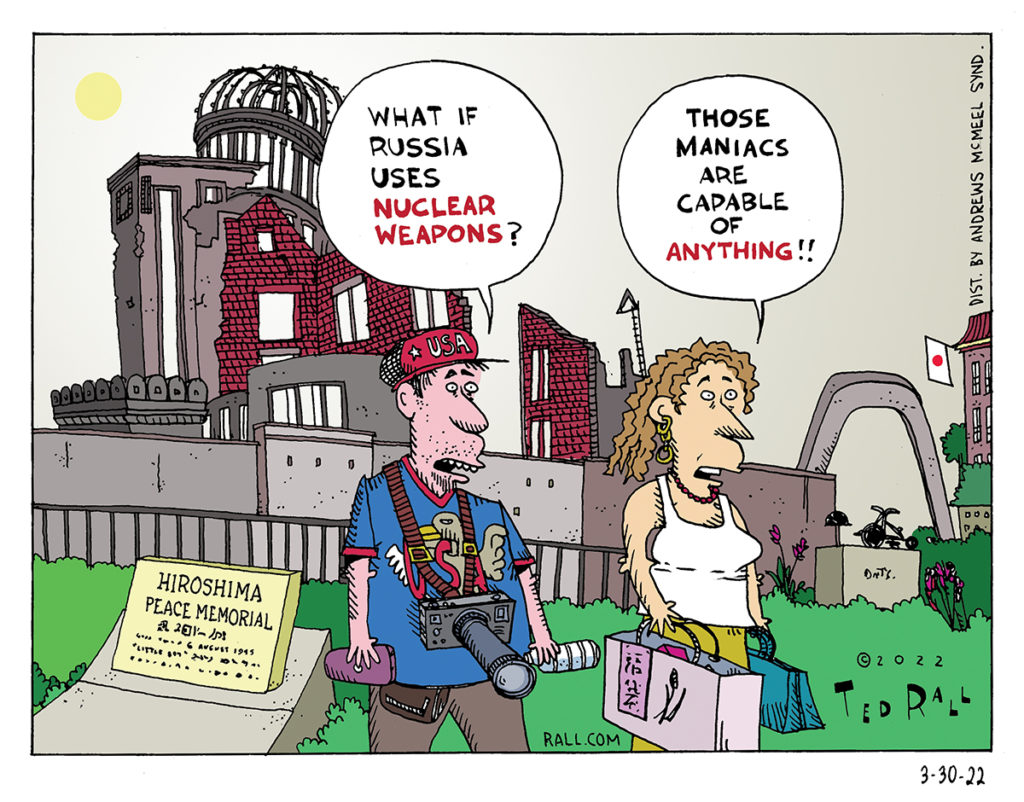

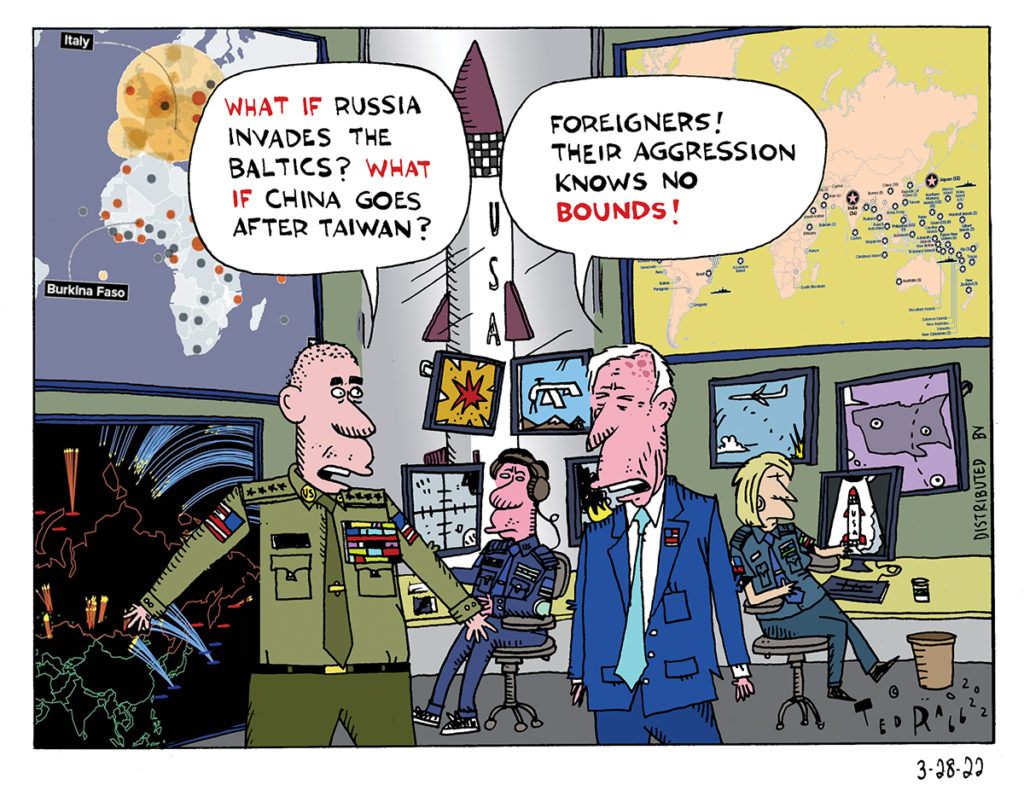

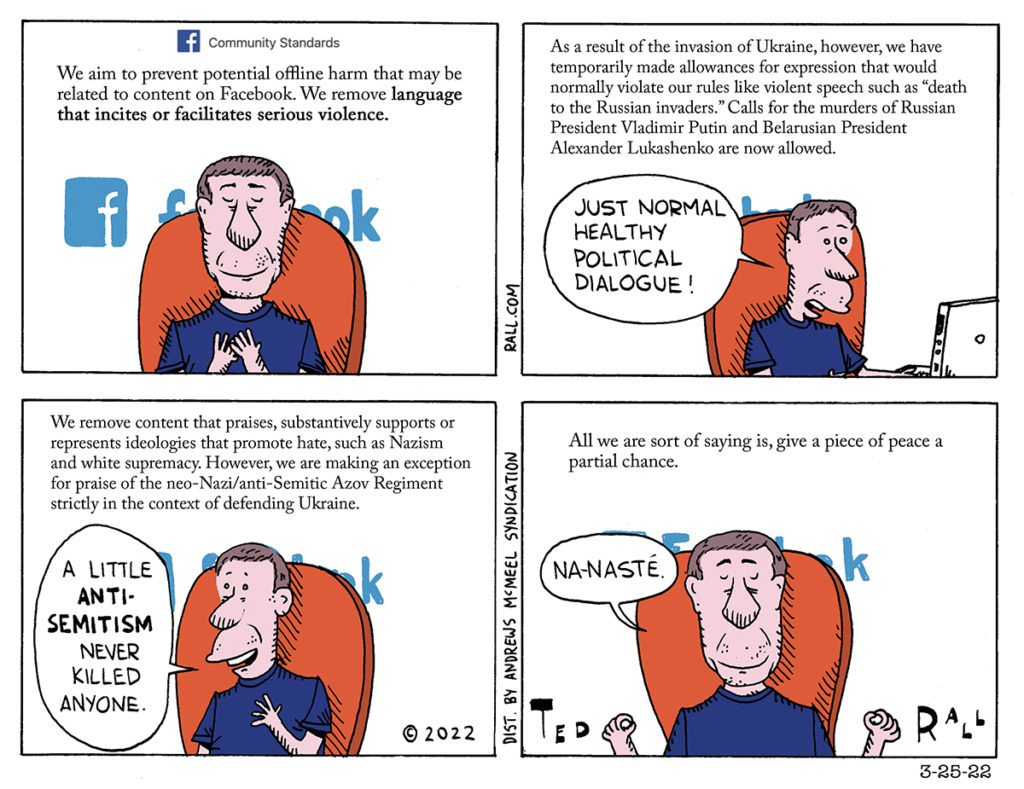

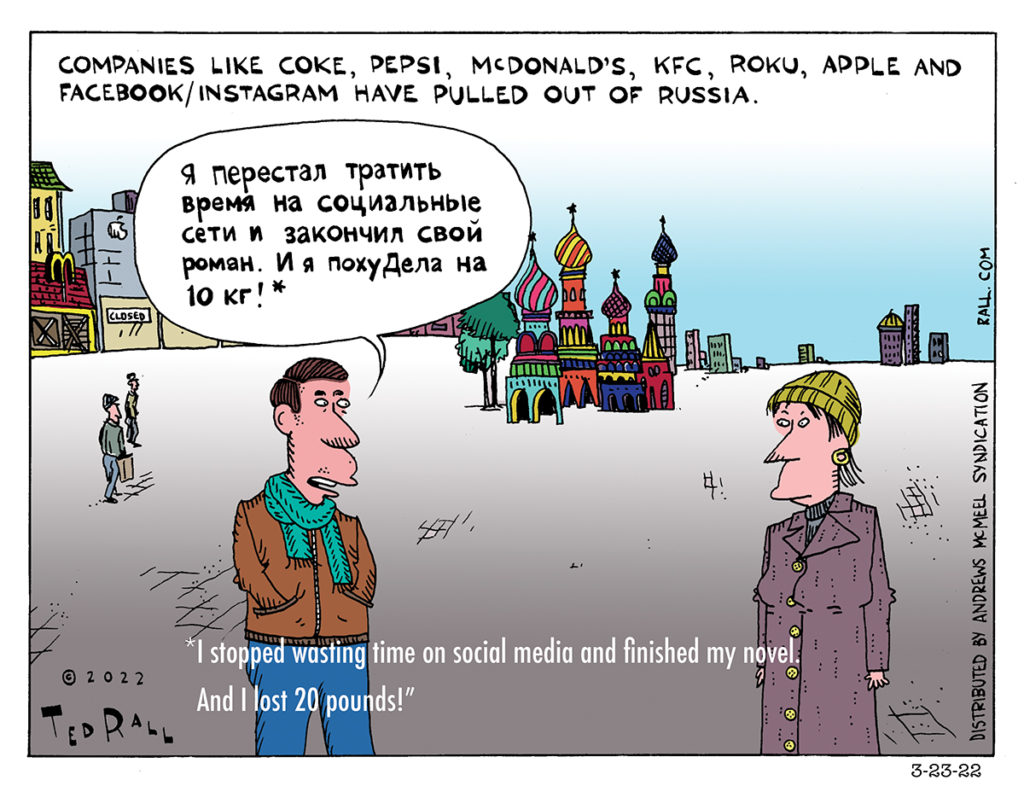

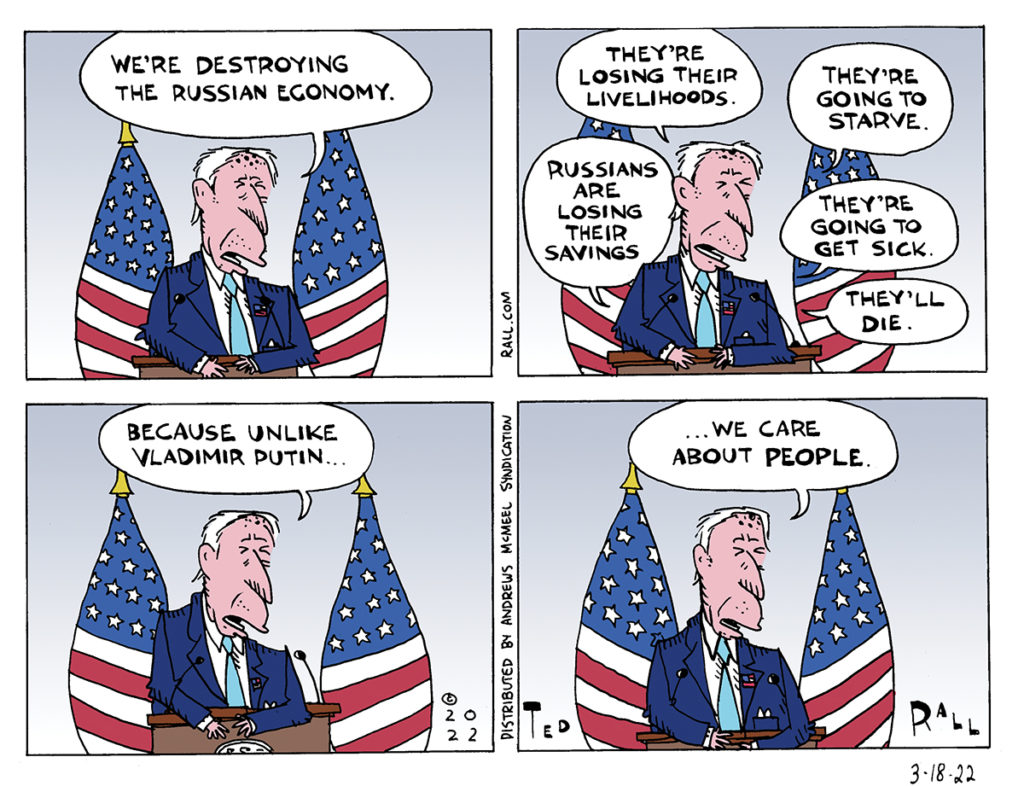

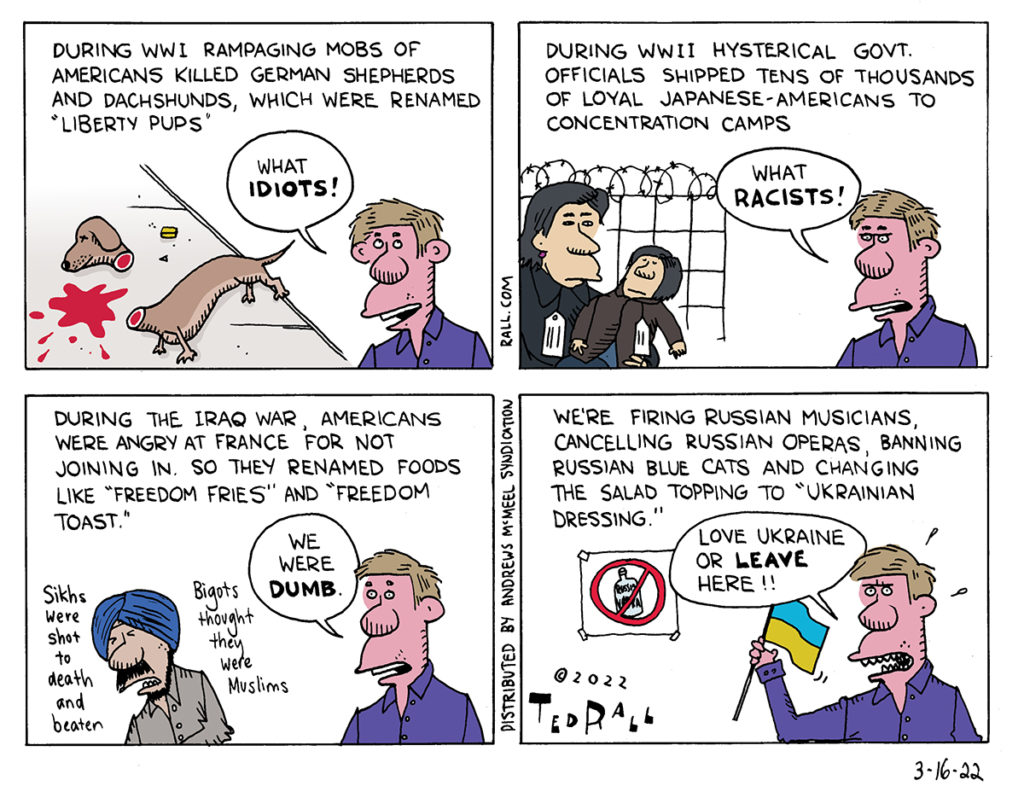

If you like your podcasts focused like a laser, this isn’t your episode. Cartoonists Ted Rall and Scott Stantis are as scattered as the world itself in their takes on foreign crises in Ukraine and the Taiwan Strait and the weird prospects for the 2024 presidential election.