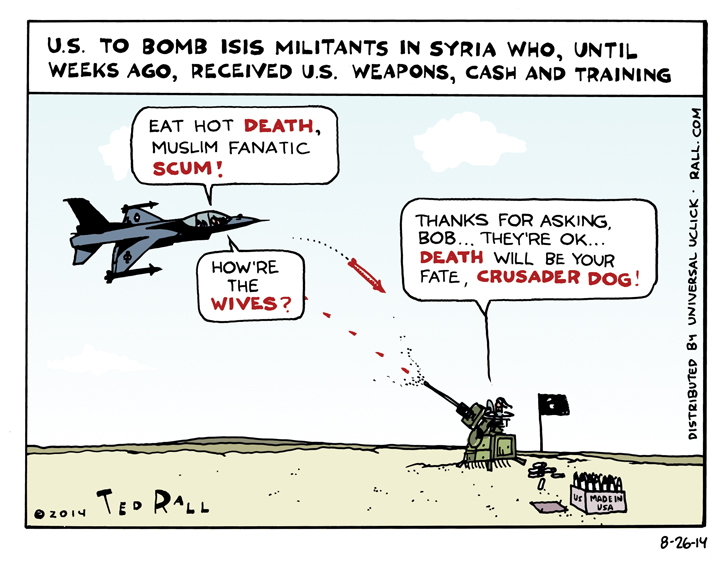

Until a few weeks ago, the United States was sending weapons and money to the Islamic State in Syria, and providing covert training both directly through the CIA and indirectly through the Gulf Arab states. Now the US is seriously considering bombing ISIS not only in Iraq, but in Syria, where we supported them in their fight against President Bashar al-Assad. At some point, this gets confusing, no?

SYNDICATED COLUMN: “Ask the Pundit”: What Should the U.S. Do About ISIS?

Reader Brian McManus asks:

“Just wondering if you can find time to post a piece on what the U.S. should do (or not do) regarding the current situation with ISIS in Iraq. Not so much on how the situation got to be where it is, but what the U.S. and/or other nations should do in situations like this. Would appreciate your thoughts on the issue.”

Thanks for writing, Brian.

Americans are “can do” people. Optimism is an appealing national personality trait but it comes with the unfortunate tendency to overestimate what can be done and its more dangerous corollary, the will to act when doing nothing would be preferable.

We saw the pitfalls of can-do following 9/11. Initial reactions to the attacks were shock and confusion. Traditional ideological divides were blurred, but in those early days one could still discern the pre-GWOT liberal tendency toward treating terrorism as a law enforcement issue, versus the old hawkish rightist desire to lash out militarily. Then the Right trotted out a line that resonated across the spectrum and caused the antiwar left to dissolve as into mist:

We have to do something.

In the United States, “something” means military action.

The thing we “have” to do “something” about always refers to foreign policy.

Americans don’t feel that “have to do something” about domestic problems. Poverty? No need to act. Corrupt bankers? Inaction is fine. But if a crisis flares up overseas (a civil war as in Syria or Libya, a siege of civilians as in Sarajevo or Iraqi Kurdistan, cross-border encroachment as in ex-Soviet Georgia or Crimea), and especially if it involves opponents the media categorizes as “bad guys” (regional economic rivals such as Iran, China or Russia, radical Islamists who may or may not have gotten their guns from us), “we” “have” “to” “do” “something” (military action).

This is not true.

There are always alternatives to military action. The success of the formerly Al Qaeda-affiliated Islamic State of Iraq and Syria insurgency, which controls half of both countries, is no exception. Half-measures come in both military (money and weapons) and non-military (political advisors) forms.

We can do nothing.

Albania is doing nothing in Iraq. Cuba is doing nothing in Iraq. Vietnam is doing nothing in Iraq. These countries have not been harmed by their refusal to intervene militarily in Iraq.

As I see it, Brian, whatever appetite ordinary Americans have for Obama’s airstrikes against ISIS and other attempts to prop up the current regime in Baghdad stems from the investment of lives and treasure the U.S. has made since the 2003 invasion.

“To be sure, the cost was high,” then-Secretary of State Leon Panetta said when Obama ordered the main troop withdrawal from Iraq. “But those lives were not lost in vain. They gave birth to an independent, free, and sovereign Iraq.”

If ISIS captures Baghdad and establishes Taliban-style Sharia law throughout Iraq, complete with amputations of accused thieves and stonings of wayward women — leaving Iraq, already in worse shape than it was under Saddam, an unequivocal nightmare for its people and a base for radical jihadis out to overthrow U.S. allies like Saudi Arabia — Panetta’s statement will have been belied.

The war will have been exposed as a total waste.

Which it was. Every American who lost a life or a limb in Iraq was sacrificed stupidly, predictably, in a war that never could have been won even had the generals and politicians in charge of it weren’t idiots.

The attempt to salvage Iraq by saving the rump Iraqi state inside the Green Zone is a refusal to accept defeat. But that doesn’t change reality.

We lost the Iraq War years ago. The sooner we accept that there is nothing to be saved there and move on, the better off we’ll be.

Undeniably and regrettably, washing our hands of Iraq — aside from leaving ISIS alone, we ought to evacuate the embassy and other government personnel Obama says we need to “protect” — will result in awful consequences. Whether or not ISIS can close the deal by capturing Baghdad, the sectarian conflict will escalate. Areas within ISIS control will be lost for the foreseeable future. More civilians will die, many as the result of “ethnic cleansing.”

We know these things will happen because we’ve lost wars before. The U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam created the “boat people” crisis, opened space for wars between Vietnam and its neighbors China and Cambodia, and permitted a communist regime hostile to U.S. interests to consolidate power, and exclude American business for decades.

But consider the alternative.

Remaining in Vietnam would have required pouring more money and more soldiers down a hole, and slaughtering countless more Vietnamese. We still would have lost. All that post-withdrawal stuff — the civil conflicts, reprisals against our former local collaborators — would still have happened. It just would have happened later.

After we accepted defeat and walked away from Vietnam, on the other hand, things eventually worked out. Vietnam is now a major U.S. trading partner; nearly half a million American tourists visit Vietnam each year.

A guy named Barack Obama once summarized his foreign policy as “Don’t do stupid stuff” like invading Iraq in the first place. Hillary’s jibes and Obama’s actions aside, it’s good advice. To which I’ll add Ho Chi Minh’s legendary order to his general Vo Nguyen Giap, who was planning the decisive 1954 battle that would expel France from Indochina: “If victory is certain, then you are to attack. If victory is not certain, then you must resolutely refrain from attacking.”

Victory against ISIS is anything but certain. Therefore, in this and similar situations, I would refrain from attacking.

(Ted Rall, syndicated writer and cartoonist, is the author of “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan,” out Sept. 2. Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2014 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

The High Price of Abortion Rights

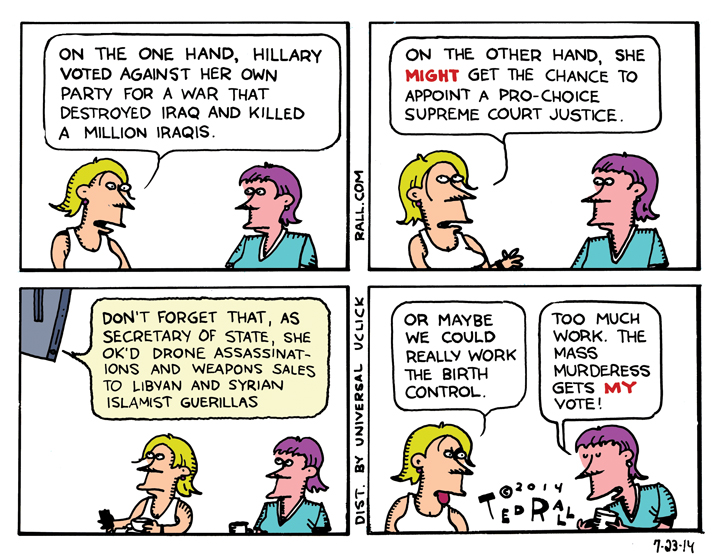

Hillary Clinton supporters are resurrecting an argument made by Obamabots to progressives: Despite her support for right-wing policies like NAFTA and voting for war against Iraq, liberals should vote for her because she might get to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court that might determine whether abortion remains legal. I’m pro-choice, but I’m nauseated by the thought that the right to an abortion necessitates voting for someone like Hillary Clinton, who has the blood of millions of innocent people on her hands.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Going After Bergdahl

Why Don’t More Soldiers Walk Away?

American news media portrays Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl and his apparent decision to simply walk away from the war in Afghanistan as bizarre and incomprehensible.

I wonder why it doesn’t happen all the time.

From The New York Times:

“Sometime after midnight on June 30, 2009, Pfc. Bowe Bergdahl left behind a note in his tent saying he had become disillusioned with the Army, did not support the American mission in Afghanistan and was leaving to start a new life. He slipped off the remote military outpost in Paktika Province on the border with Pakistan and took with him a soft backpack, water, knives, a notebook and writing materials, but left behind his body armor and weapons — startling, given the hostile environment around his outpost.”

There’s little doubt. Bergdahl was politicized by what he saw.

“The future is too good to waste on lies,” a 2012 Rolling Stone article quotes an email from Bergdahl to his father. “And life is way too short to care for the damnation of others, as well as to spend helping fools with their ideas that are wrong. I have seen their ideas and I am ashamed to even be American. The horror of the self-righteous arrogance that they thrive in. It is all revolting.”

Among other traumas, the then 23-year-old Idaho native witnessed an Afghan child run over by a U.S. Army vehicle. His fellow soldiers, he recalled, didn’t seem to care.

The Times paints a portrait of a soldier who was alienated, burned out and possibly a victim of PTSD. “He wouldn’t drink beer or eat barbecue and hang out with the other 20-year-olds,” the paper quotes Cody Full, a member of Sergeant Bergdahls platoon, in an interview arranged by the Republican Party. “He was always in his bunk. He ordered Rosetta Stone for all the languages there [in Afghanistan], learning Dari and Arabic and Pashto.”

Bergdahl’s walk-away echoes Tim O’Brien’s allegorical 1978 novel “Going After Cacciato,” in which a U.S. soldier serving in Vietnam goes AWOL, determined to walk all the way to Paris. His buddies go after him. It soon becomes clear that Cacciato’s comrades are less interested in catching him than in following his example.

All military forces contend with deserters, and the United States is no exception. “Army desertion rates have fluctuated since the Vietnam War — when they peaked at 5 percent. In the 1970s they hovered between 1% and 3%, which is up to three out of every 100 soldiers. Those rates plunged in the 1980s and early 1990s to between 2 and 3 out of every 1,000 soldiers,” according to NBC News. By 2007, the fourth year of the U.S. occupation of Iraq, the rate was up 80%, to nine out of 1,000.

450,000 U.S. troops deserted during Vietnam.

Few deserters pull a Cacciato, opting out in the combat zone. Instead, while on leave, most just fail to report back.

Given the conditions faced by many U.S. soldiers in war zones, it’s surprising that more don’t lose it and take off.

Contrary to standard practice among armed forces in the West for hundreds of years, American soldiers are assigned to repeated, long combat tours without sufficient time between missions to recuperate. They are often underequipped and, as was apparently the case in Bergdahl’s unit, poorly disciplined and rarely given any context for their operations.

Then there’s the nature of the wars themselves.

Since 1945, since they weren’t authorized by Congress, every single one of America’s wars have been illegal. They’ve all been wars of aggression — neither the Koreans nor the Vietnamese nor the Iraqis nor the Afghans posed any threat to the United States. And they’ve all featured aspects of what historians dubbed “total war” after World War II: combat in which civilian casualties are not regrettable accidents, but strategically considered and intentional.

When soldiers become vets, they’re cast out into the streets, where many become homeless.

It doesn’t take long for the truth to hit home. All but the stupidest active-duty soldiers realize that they’re peasant mercenaries for a cruel and uncaring empire.

Why don’t more guys (and women) pull a Bergdahl? The main incentive to remain at their posts has to be the unremitting hostility of the locals — something Bergdahl no doubt experienced during five long years of captivity.

(Ted Rall, Staff Cartoonist and Writer for Pando Daily, is the author of the upcoming “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan.” Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2014 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Reparations for Blacks? For an Exceptionally Vicious Nation, Just a Start

In the latest of periodic revivals of the argument that the United States ought to issue reparations to African-Americans as compensation for slavery, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in The Atlantic: “Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.”

That discrimination, poverty and genocide are at the heart of the black American experience is not in doubt — at least not in the minds of people of moderate intelligence and good will. That tens of millions of blacks continue, “even” after the election of the first black president, to suffer systemic racism along with its attendant symptoms — schools starved of funding, grinding poverty, police brutality, a viciously skewed judiciary, bigotry in every aspect of life from the workplace to housing to romance — is obvious to all who care to open their eyes the slightest bit.

Reparations are obviously justified. Moreover, they are normative; in the United States, aggrieved parties routinely seek and receive compensation for their injuries and economic losses via class-action lawsuits and the occasional U.S. Treasury payout. During the 1990s, for example, Congress issued $20,000 reparations checks to 82,210 Japanese-Americans and their heirs in order to compensate them for shipping them to concentration camps during World War II (and, in many cases, stealing their homes and businesses).

Better ridiculously late than never; better insultingly small than nothing.

Other U.S. reparations precedents include North Carolina residents forcibly sterilized during the mid 20th century as part of a nationwide eugenics program targeted at minorities and the mentally disabled (they are receiving $50,000 each), victims of the infamous Tuskegee untreated-syphilis experiment ($24,000 to $178,000), and blacks killed in the 1923 mass lynching at Rosewood, Florida ($800,000 for those forced to flee).

Coates admits that complications arise from his proposal: “Who will be paid? How much will they be paid? Who will pay?”

Should blacks who are not descendants of American slaves, like President Obama, receive reparations? What about wealthy blacks — should a wealthy black person receive a payout while members of other races go hungry? Should poor blacks get more than rich blacks? What about “mixed race” people — if your father was black and your mother was white, should you get half a check?

These are good questions, but as a white man (not descended from Americans who lived in the United States during slavery), I don’t enjoy the political standing to ponder them, much less answer them.

Whatever the details of a theoretical reparation scheme, my only objection to the idea overall would be that no amount of money would or could be enough. Reading through Coates’ survey of centuries of savage rape, abuse and degradation, one can’t help but ask, how could $100,000 make up for a single ancestor turned away from restaurants or rejected for promotions or unable to attend college due to the color of her skin? $1 million? $10 million?

Not that doing the right thing is going to happen any time soon. “For the past 25 years, Congressman John Conyers Jr., who represents the Detroit area, has marked every session of Congress by introducing a bill calling for a congressional study of slavery and its lingering effects as well as recommendations for ‘appropriate remedies,’ Coates writes.

The bill “has never—under either Democrats or Republicans—made it to the House floor,” he says, because “we are not interested.”

Well, I’m interested. And I’d be paying, not getting.

Coates is, if anything, too polite. Congress’ disinterest in trying to atone for America’s original sin of slavery, he says, “suggests our concerns are rooted not in the impracticality of reparations but in something more existential.”

That existential something, of course, is that the United States and its economic infrastructure are the products of so much brutality, stealing, lying and exploitation, of so many hundreds of millions of people not only within “our” borders but — as the center of a vast economic and military empire — that it would not only be impossible to compensate all of its victims without going broke many times over, reparations would force American political leaders to concede that we are indeed an exceptional nation, if only in our violence and perfidy.

One place to start compiling lists of victims and heirs to consider for reparations would be Howard Zinn’s “People’s History of the United States.” All 49 states (except Hawaii) belonged to Native Americans; any fair assessment of compensation would give the total real estate value back to them, plus four centuries of interest and penalties for pain, suffering, and opportunity cost. Hawaii was stolen from native Hawaiians by an invasion force of U.S. Marines.

Chinese railroad workers were abused, discriminated against and in some cases murdered; America’s freight travels the rails they laid down. Except for slavery, Latinos too have suffered many of the same horrors, and still do, as Coates enumerates. There are the victims of America’s countless wars of colonial conquest in North America and around the world: Filipino patriots tortured to death in the early 20th century, two million Vietnamese, Koreans, Afghans, Iraqis and Yemenis — honestly, this is like one of those Oscar speeches where there isn’t enough time to thank everyone who made this “wonderful” exceptional country possible.

By all means, cut everyone a check, then close up shop.

(Support independent journalism and political commentary. Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2014 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

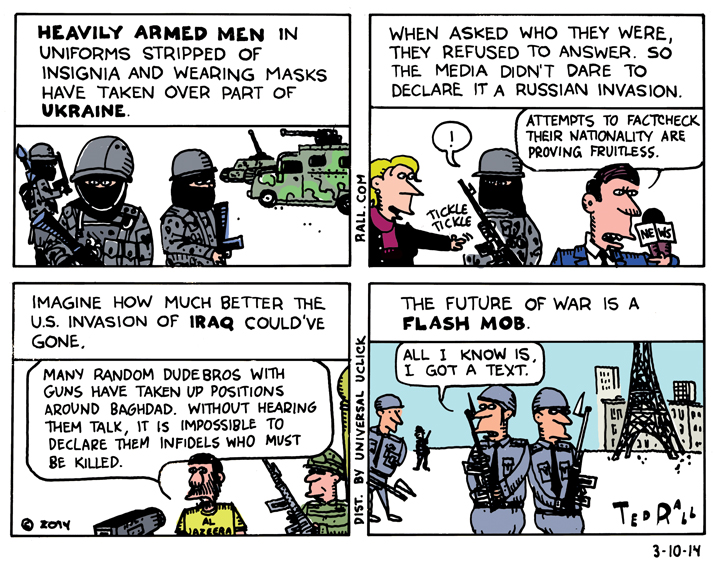

Flash War

Heavily-armed men who took over Crimea last week refused to say who they were, so foreign media outlets dutifully refused to accuse Russia of invading Ukraine until after it had happened. Imagine how much better the invasion of Iraq would have gone if nobody had been able to blame the United States for it?