Ten Years into the Iraq War, the U.S. Repeats in Syria

The Quagmire Pattern always seems to play out the same way.

There’s a civil war in some country deemed by the CIA to be Of Strategic Importance (i.e., energy reserves, proximity to energy reserves, or potential pipeline route to carry energy reserves).

During this initial stage, a secular socialist dictatorship fights Muslim insurgents who want to create an Islamist theocracy. To build public support – or at least apathetic tolerance – the conflict is cast to and by the media as a struggle between tyrannical torturers and freedom-loving underdogs.

The U.S. must get involved!

If not us, who?

Alternative answers to this question – the European Union, the African Union, the United Nations, or nobody at all – what about self-determination? – are shrugged off. It is as if no one has said a word.

The Pentagon selects a rebel faction to support, typically the most radical (because they’re the most fanatical fighters), and sends them money and weapons and trainers.

It works. The regime falls. Yay!

Civil war ensues. Not so yay.

The craziest religious zealots are poised to prevail in this second stage. Because they’re militant and well-trained (by the U.S.). Suffering from buyers’/backers’ remorse, American policymakers have a change of heart. Pivoting 180 degrees, the U.S. now decides to back the most moderate faction (because they’re the most reasonable/most pro-business) among the former opposition.

Then the quagmire begins.

The trouble for Washington is, the radicals are still fanatical – and the best fighters. Minus outside intervention, they will win. So the U.S. pours in more help to their new moderate allies. More weapons. Bigger weapons. More money. Air support. Trainers. Ground troops. Whatever it takes to win an “honorable peace.” And install a moderate regime before withdrawing.

If they can withdraw.

The moderates, you see, never enjoyed the support of most of their country’s people. They didn’t earn their stripes in the war against the former regime. Because of U.S. help, they never had to up their game militarily. So they’re weak. Putting them in power isn’t enough. If the U.S. leaves, they collapse.

Boy, is the U.S. in a pickle now.

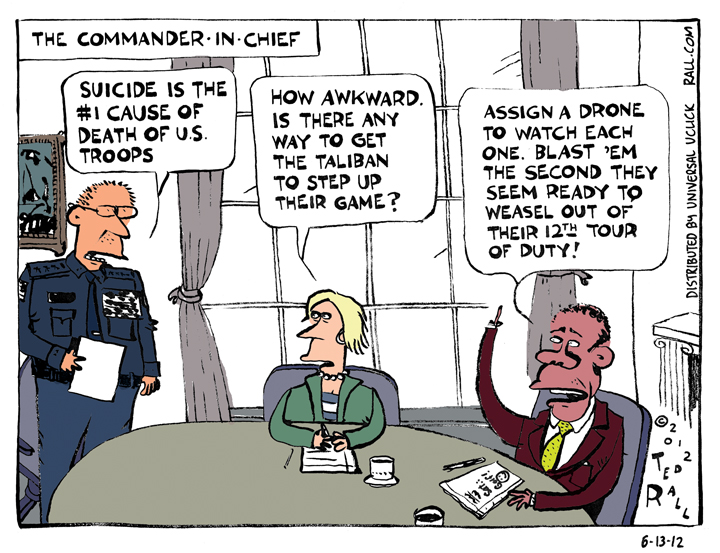

Americans troops are getting offed by a determined radical insurgency. The harder the Americans try to crush the nuts, the stronger and bigger they get (because excessive force by invaders radicalizes moderate – but patriotic – fence sitters). Moreover, their puppet allies are a pain in the ass. Far from being grateful, the stooges resent the fact that the U.S. armed their enemies during the original uprising against the fallen dictatorship. The puppet-puppetmaster relationship is inherently one characterized by mistrust.

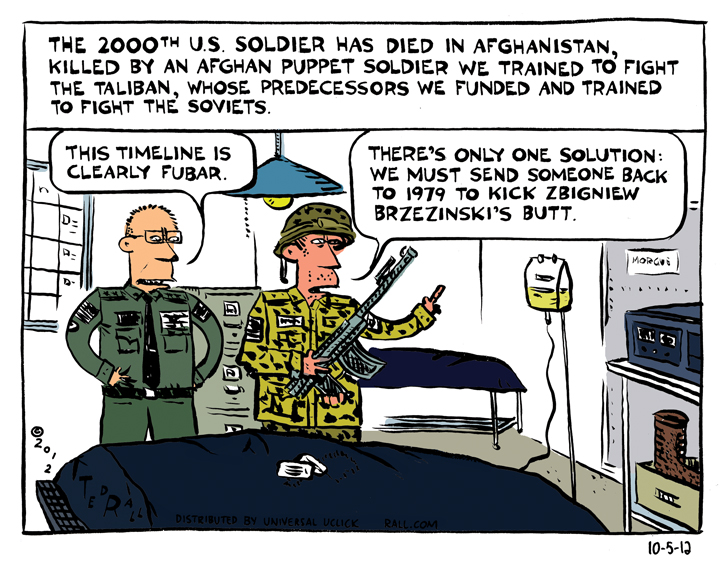

Starting with the Carter and Reagan Administrations’ arming of the anti-Soviet mujahedeen in Afghanistan during the 1980s and continuing today with the ineffectual and ornery Hamid Karzai, the Quagmire Pattern is how the U.S. intervention unfolded in Afghanistan.

However, the American electorate isn’t told this. They are repeatedly told that abandonment – as opposed to isolationism – is the problem. “The decisive factor in terms of the rise of the Taliban and al-Qaida was the fact that the United States and most of the international community simply walked away and left it to Pakistan and to other more extremist elements to determine Afghanistan’s future in the ’90s,” claims James Dobbins, former U.S. envoy to Afghanistan, Bosnia and Kosovo in a standard retell of the Abandonment Narrative.

The logical implication, of course, is that the U.S. – er, the “international community” – shouldn’t have left Afghanistan in the early 1990s. We ought to have remained indefinitely. The problem with this argument is that we have been over there for 12 straight years, and have little to show for our efforts. (It also ignores history. The U.S. was involved in the 1996-2001 Afghan civil war. It helped both sides: weapons to the Northern Alliance, tens of millions of dollars to the Taliban.)

The Abandonment Narrative is total bullshit – but it has the force of media propagandizers behind it.

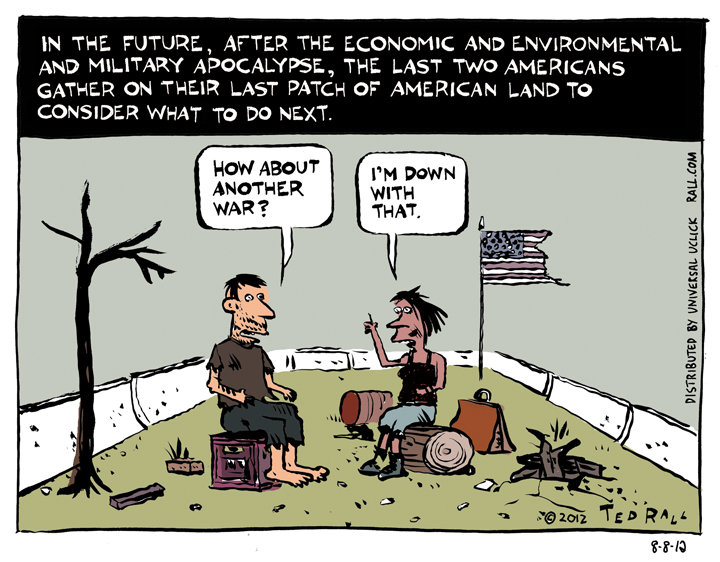

The Quagmire Pattern has played out in Afghanistan. And in Iraq. Again in Libya, where a weak central government propped up by the Obama Administration is sitting on its hands as Islamist militias engage in genocide and ethnic cleansing.

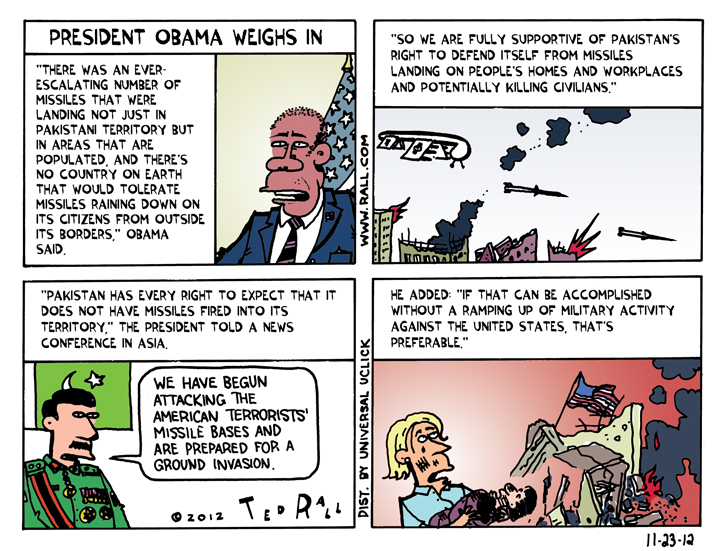

Now the Quagmire Pattern is unfolding again, this time in Syria. When the uprising against the secular socialist government of Bashar al-Assad began two years ago, the U.S. rushed in with money, trainers and indirect arms sales. Jihadis received most of the bang-bang goodies. Now people like Dobbins are arguing in favor of weapons transfers from Pentagon arms depots to the Syrian opposition. And President Obama is considering using sketchy allegations that Assad’s forces used chemical weapons – here we go again with the WMDs – as a pretext for invading Syria with ground troops.

Dobbins admits that there are “geopolitical risks,” including distracting ourselves from America’s other Big Possible Future War, against Iran. Yet he still wants to arm the Syrian rebels, who include members of Al Qaeda.

There is, he told NPR, “the possibility that the intervention wouldn’t work and that it would look like a failure.”

“Possibility”? Such interventions have never worked.

So why does he still want to give weapons to people who will probably wind up aiming them at American soldiers?

“I think the consequences of not acting and the risks of not acting are even greater.”

In other words: we do what we do because that’s what we do.

That’s how the Quagmire Pattern works.

(Ted Rall’s website is tedrall.com. His book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan” will be released in November by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

COPYRIGHT 2013 TED RALL