Live at 10 am Eastern time/8 am Mountain and Streaming all the time after that:

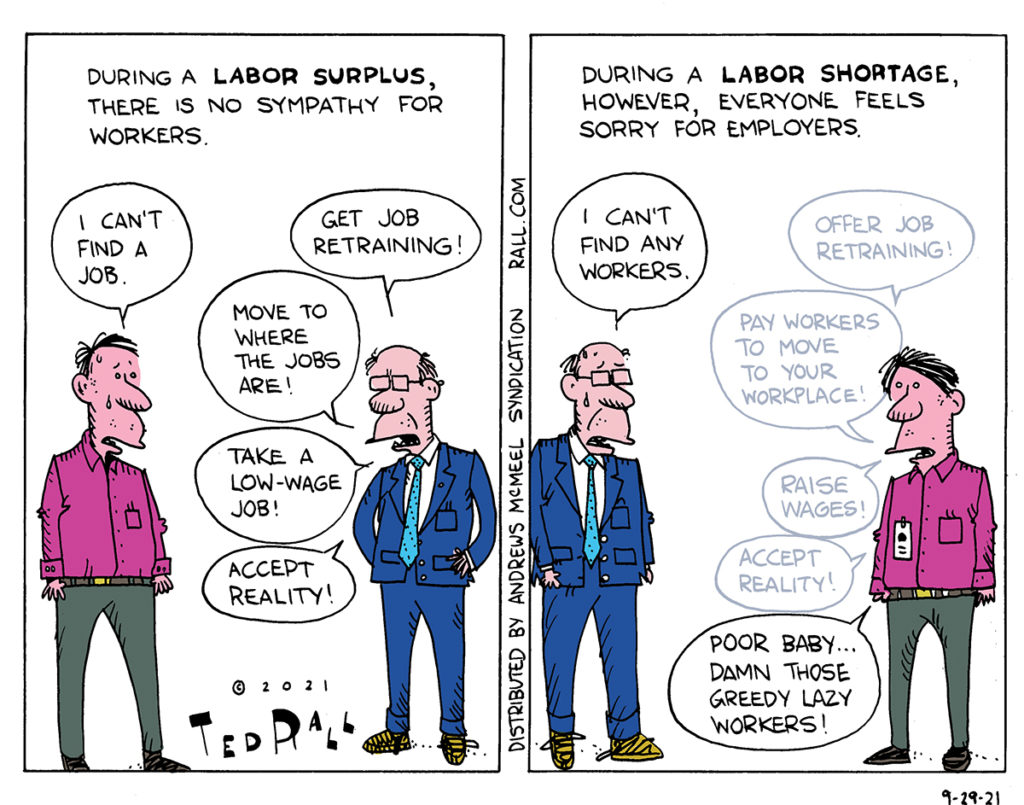

Bearing the same subject line as a downsizing memo sent to Twitter employees by Elon Musk, an ominous mass email was fired out by the Trump Administration to millions of federal employees offering them a buyout if they voluntarily agree to resign within a week. There is a fist inside the velvet glove: most federal agencies will probably be slashed and a substantial number of employees will be furloughed or reclassified to “at-will status,” making them easier to fire. Most remote workers will have to go back to the office. And many will have their offices moved elsewhere.

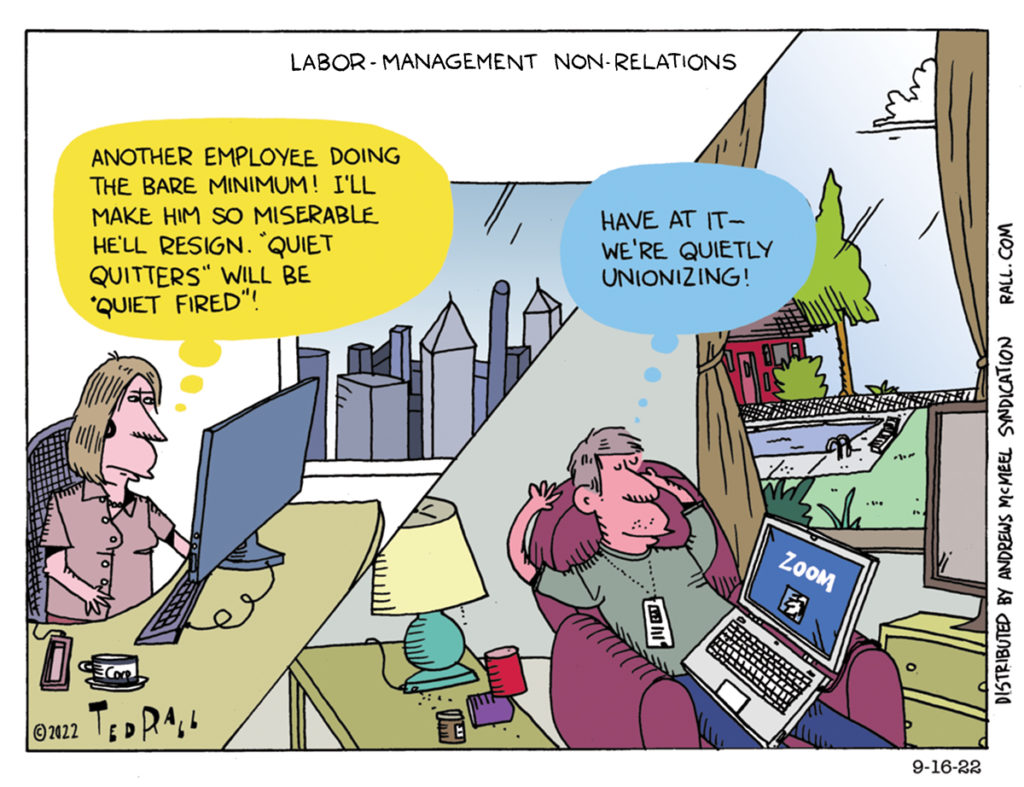

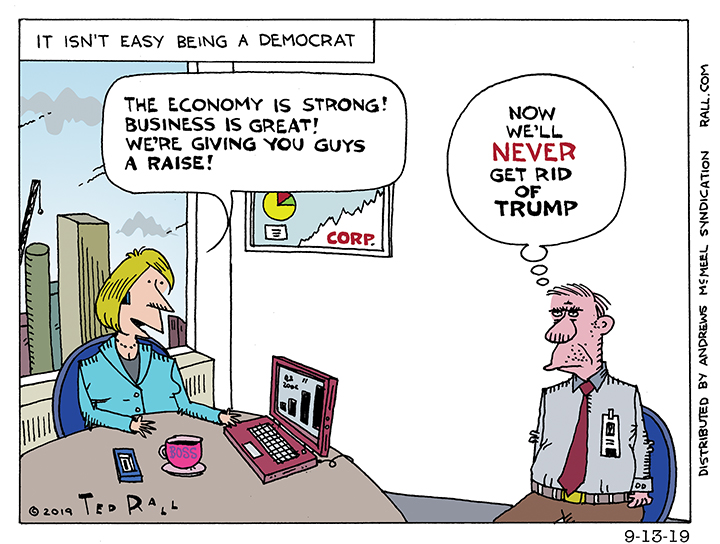

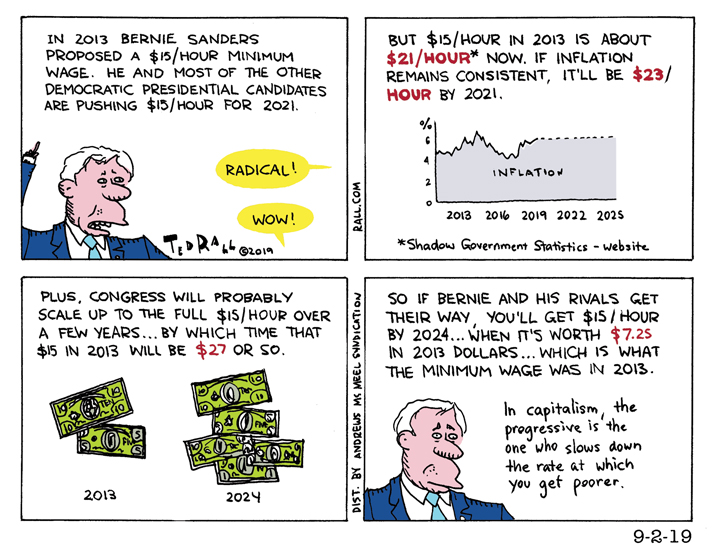

On “The TMI Show,” co-host Manila Chan is out sick. Filling in for Manila is Robby West, alongside co-host Ted Rall. Robby and Ted will discuss whether Trump has the power to pay buyouts, the possibility of court battles, the pros and cons of remote work and whether this disrespectful treatment of government workers is fair.

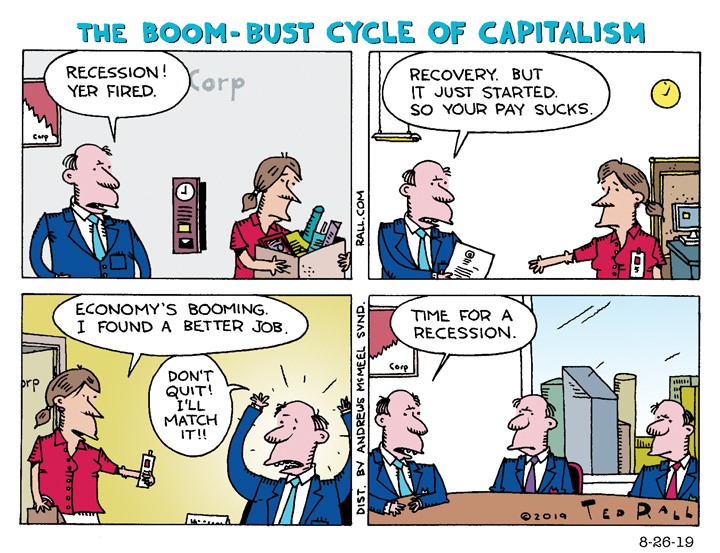

Serendipity plays such a starring role in our lives that we never stop to ask ourselves whether we ought to accept it. A random event, especially one that turns out to be your “big break,” becomes a charming story—even though, really, such happenstance is an indictment of a system that is no system at all.

Serendipity plays such a starring role in our lives that we never stop to ask ourselves whether we ought to accept it. A random event, especially one that turns out to be your “big break,” becomes a charming story—even though, really, such happenstance is an indictment of a system that is no system at all.