Live at 10 am Eastern/8 am Mountain time and Streaming anytime 24-7 thereafter:

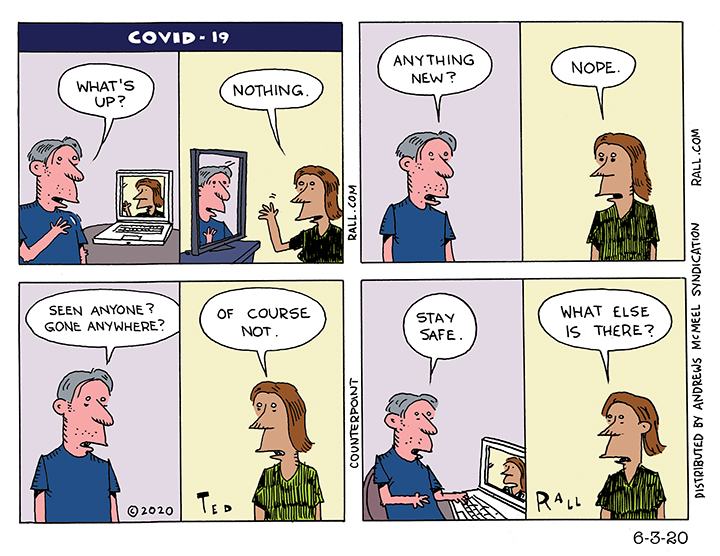

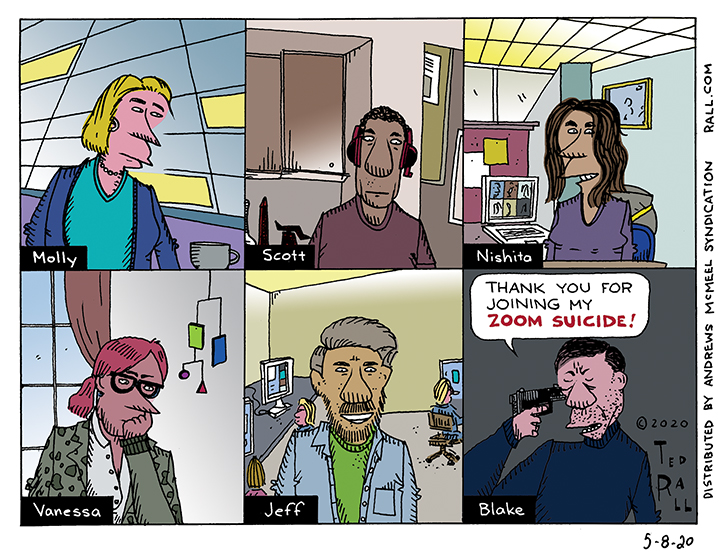

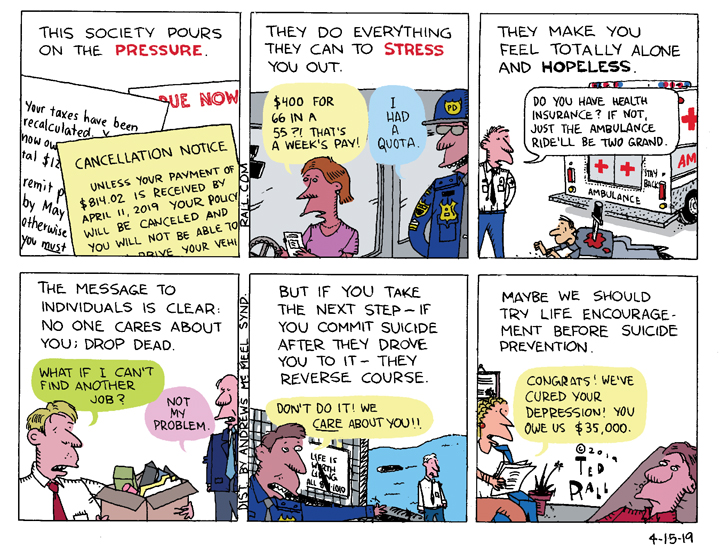

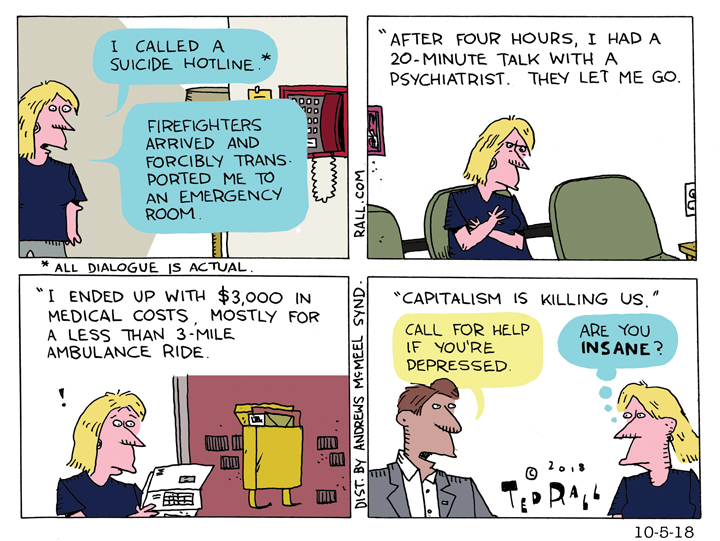

America rock ‘n’ rolled all night long and partied every day. Then Boomers started dying, Gen X started having babies, Millennials fell in love with their phones and the pandemic kept us locked up. Only 4.1 percent of Americans attended or hosted a social event on an average weekend or holiday in 2023, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics–a 35% decline since 2004. Party City announced that it would close after years of flagging sales. Teens are engaging in markedly fewer risky behaviors than they used to a major cause is that teenagers are having fewer parties.

After the Spanish flu pandemic, Americans raged through the Roaring Twenties. Why aren’t we doing the same?

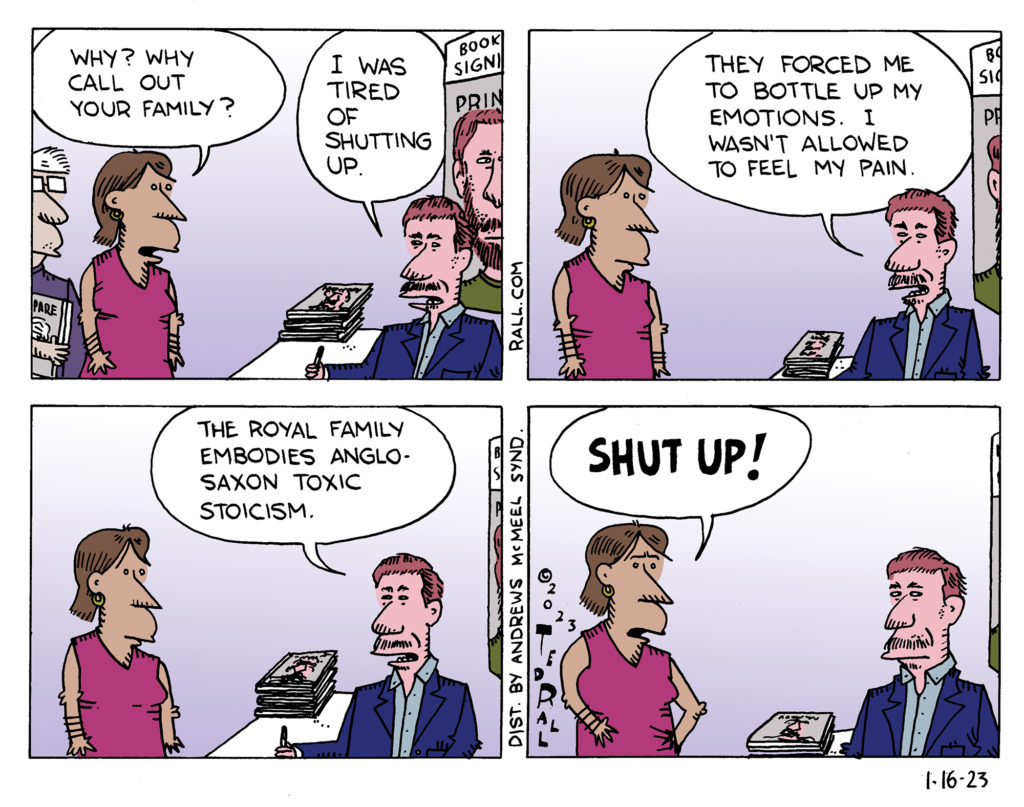

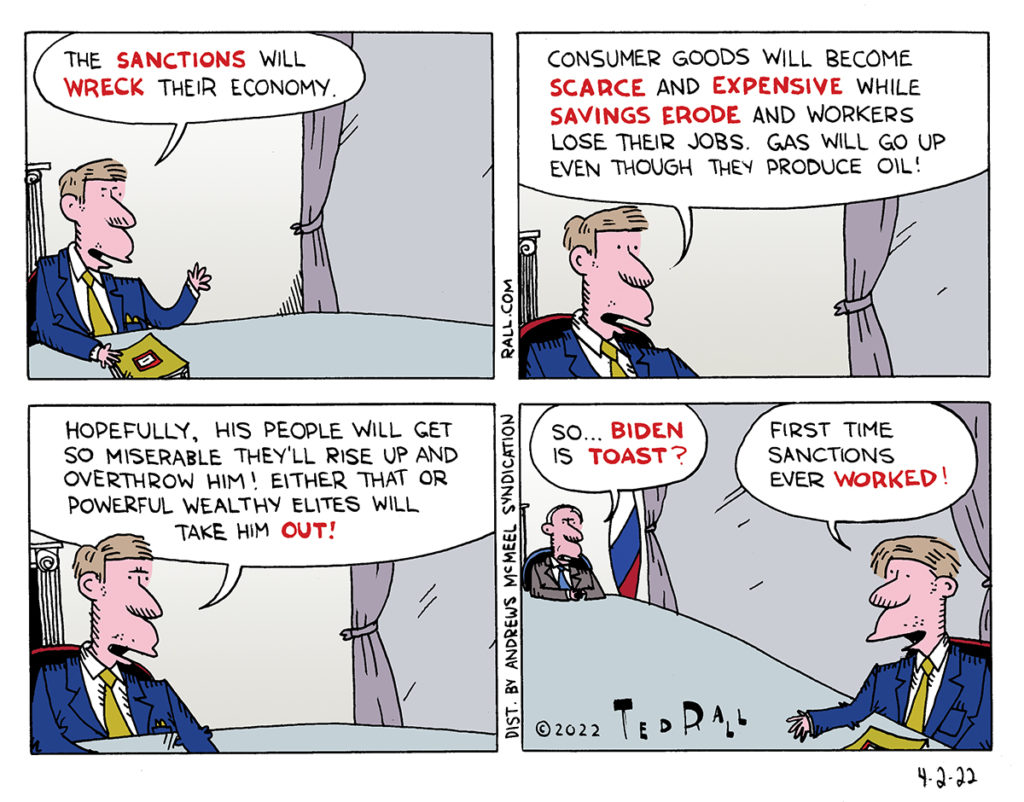

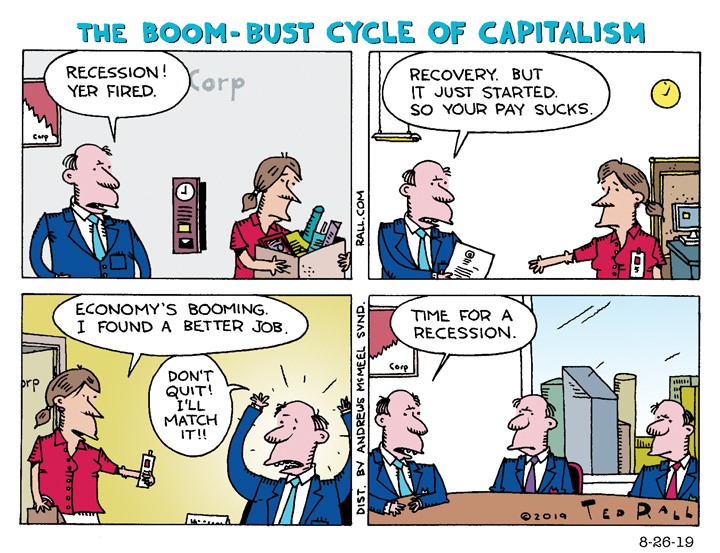

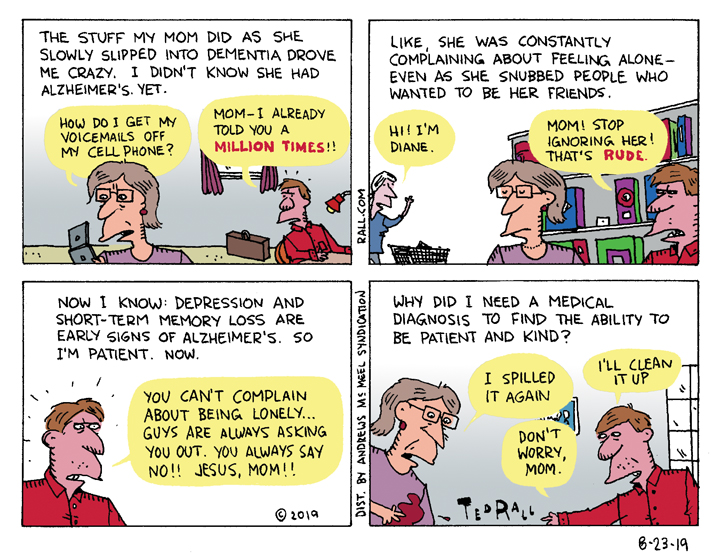

Is life without fun worth living? On “The TMI Show” party animals Ted Rall, Manila Chan and guest Scott Stantis of The Chicago Tribune ask whether ennui and angst are driving our politics and whether we’ll again ever do things we’d regret if we remembered them.