Investigators are still putting together the pieces, but from what we know so far, it’s likely that 27-year-old German co-pilot Andreas Lubitz committed mass murder-suicide when he flew a Germanwings passenger jet carrying 149 passengers and fellow crewmen into the French Alps.

Authorities say they haven’t found a suicide note, but it’s a safe bet that Lubitz’s final act was prompted by depression (they found the meds), diminished vision, a deteriorating romantic relationship and his worry that the Lufthansa subsidiary would ground him if they found out about his problems, crashing a career he loved and blowing up his livelihood.

Though rare, pilot suicide isn’t unheard of. As long as the current system remains in place, it will happen again.

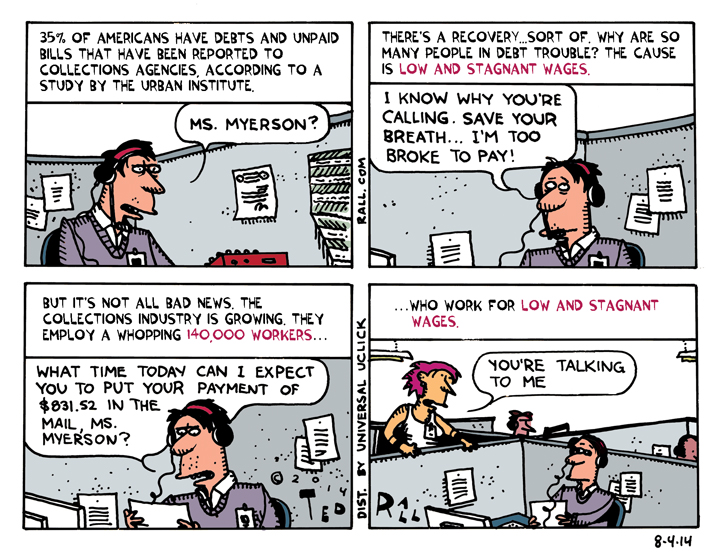

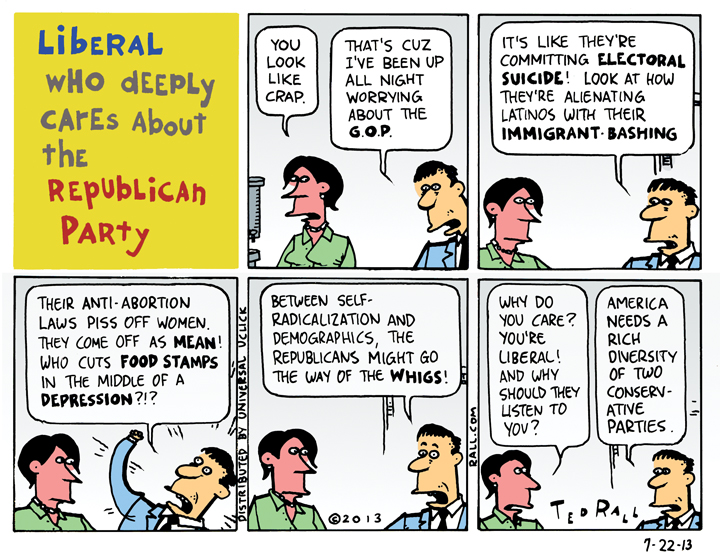

By “system,” I’m referring both to specific rules issued by the FAA and other countries’ aviation authorities to regulate pilots, and to that most coldhearted of socioeconomic systems, you’re-on-your-own capitalism.

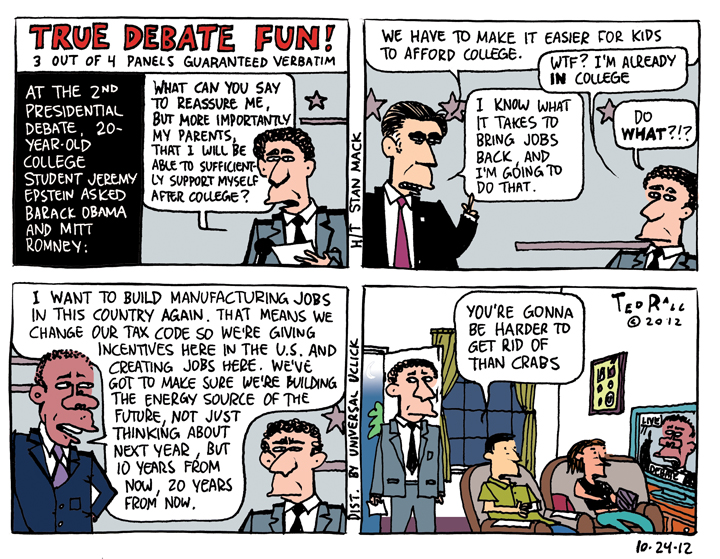

“Before they are licensed, pilots must undergo a medical exam, conducted by a doctor trained and certified by the aviation agency,” explains The New York Times. Some airlines impose additional screening procedures, but they vary from company to company. Active pilots are required to have a medical screening once a year until they turn 40 and then twice a year after. Only when pilots are found to have mental health problems are they sent to a psychiatrist or psychologist for evaluation or treatment.”

At first glance, an incident like the Germanwings disaster seems to call for increased physical and mental monitoring. But leaning harder on pilots would only fix half the problem.

The current system is punitive – thus it encourages lying.

“But the system, Dr. [Warren] Silberman [a former manager of aerospace medical certification for the FAA] and others said, leaves pilots on an honor system, albeit one reinforced by penalties to discourage them from concealing any health issues that could affect their fitness to fly, including mental illness. Pilots who falsify information or lie about their health face fines that can reach $250,000, according to the FAA.”

Imagine yourself in that position. Knowing that public safety is at risk, you might do the right thing and step forward after your psychiatrist tells you that you shouldn’t be working, as happened to Lubitz. Then again, you might not.

First of all, you might doubt the diagnosis. That’s the thing about mental illness – victims’ judgment can be impaired. For example, there is evidence that Ronald Reagan suffered from early signs of dementia while serving as president. If true, that’s scary – but was the Gipper aware he was fading?

Second, you might think you could handle it, that with the help of psychiatric treatment and antidepressant medications, you could push through what might turn out to be a temporary crisis. Why risk everything over a passing phase?

Third, and this is likely, you might keep your problems to yourself because to do otherwise would ruin your life – or at least feel like it. At bare minimum, it would end your career, forcing you to start from zero. For many people, that seems too horrible to bear. In our society, social status is determined by our careers.

“The stigma [of having a mental illness] is enormous,” Dr. William Hurt Sledge, professor of psychiatry at Yale who has consulted for the FAA, the Air Line Pilots Association and major airlines, told the Times. “And of course, none of them wants that to be known, nor do they want to confess it or believe that they have it.”

And for those who decide to ignore the stigma, what comes next? Where’s the safety net, professional, social and economic, for people who run into trouble, whether of their own making or not?

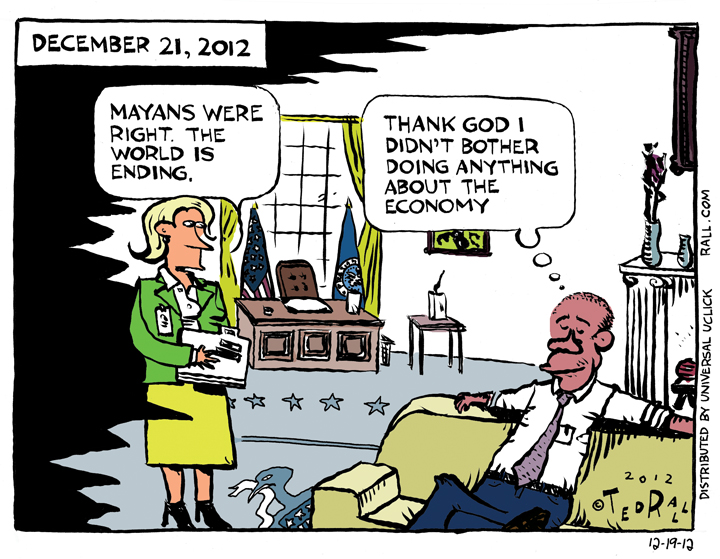

At the root of Lubitz’s decision to kill himself – whether he gave much thought to the 149 people on the other side of the reinforced cockpit door cannot be known – is that he lived, as we all do in the Western world, in a disposable society. Lose what you do and you lose what you are. The bills keep coming long after the paychecks stop; soon you have nothing left.

I could throw a dart at any daily newspaper to illustrate this point; today it would probably land on the results of an AARP survey that found – unsurprisingly to anyone over age 50 – that a single layoff after that age has devastating, long-term consequences. People over 50 are overwhelmingly more likely to wind up classified among the long-term unemployed and typically wind up earning less if and when they find a new job, often starting again from scratch in a new industry because their experience was in a line of work that no longer has openings.

I imagine a system in which people like Andreas Lubitz don’t need to see a psychological or other setback as the end of their world.

What if he could have confided in his bosses without fear? What if Lufthansa policy was to stand by him through his treatment, guaranteeing him a respectable job at equivalent salary – for as long as it took for him to get better? And if he couldn’t recover, what if he knew that his country’s government would provide for him financially and otherwise? Finally, what if no one cared what he did for a living, and it was just as prestigious and remunerative to work as a file clerk as to fly a plane?

I’m not sure, but I bet 150 people would be alive today.

(Ted Rall, syndicated writer and the cartoonist for The Los Angeles Times, is the author of the new critically-acclaimed book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan.” Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2015 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM