Check it out!

Hollywood Should Totally Make a Movie from my book “The Year of Loving Dangerously”

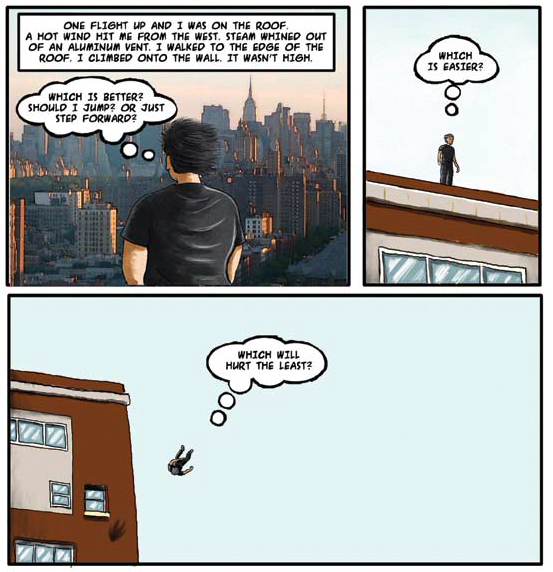

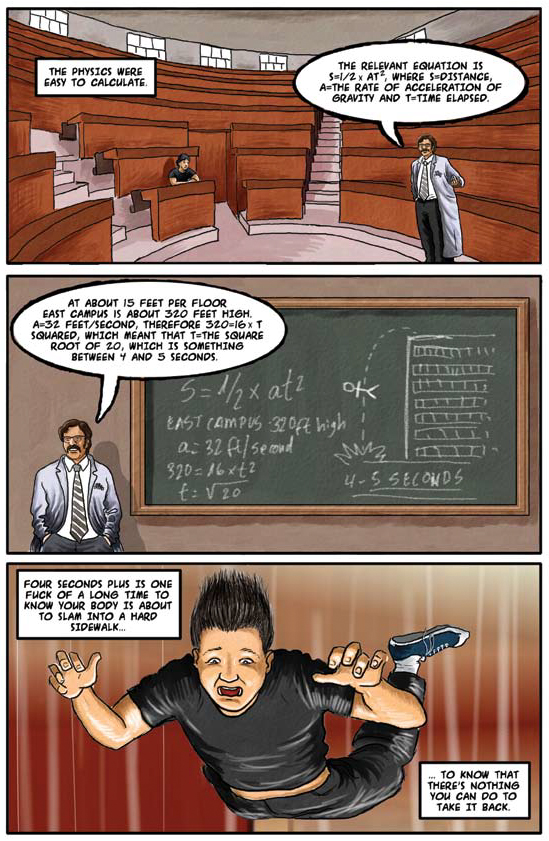

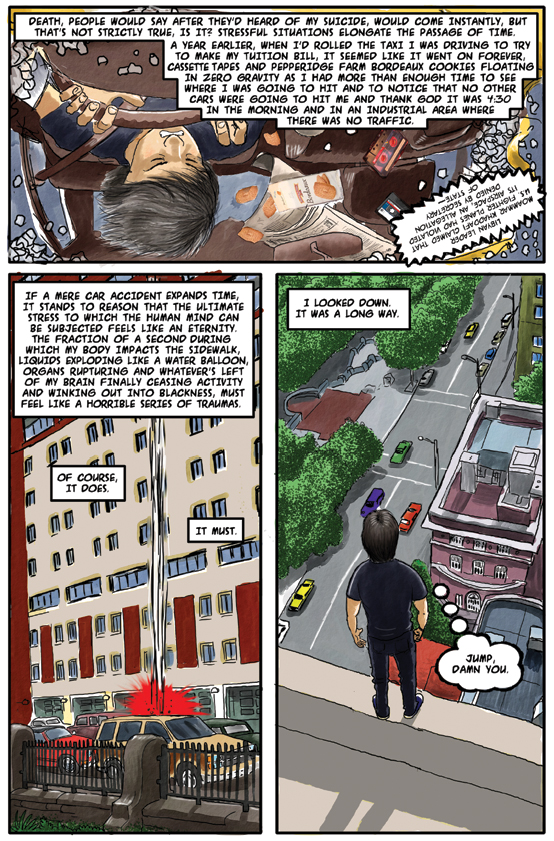

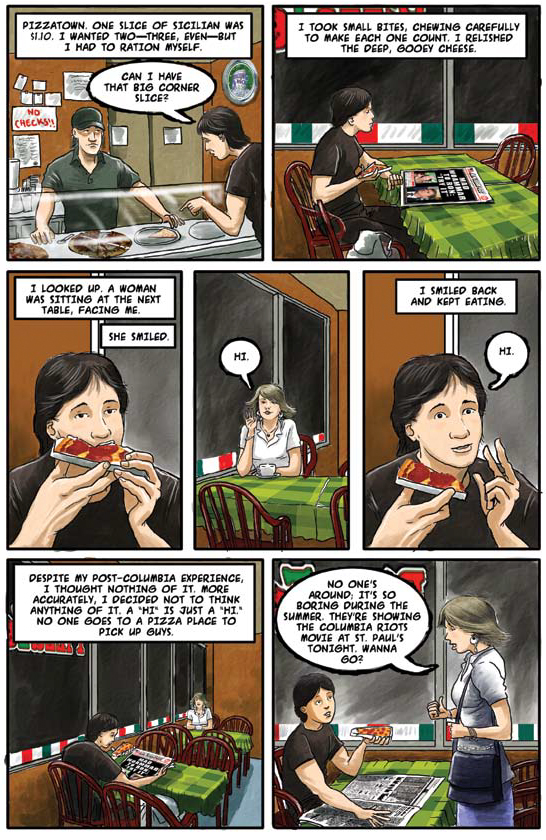

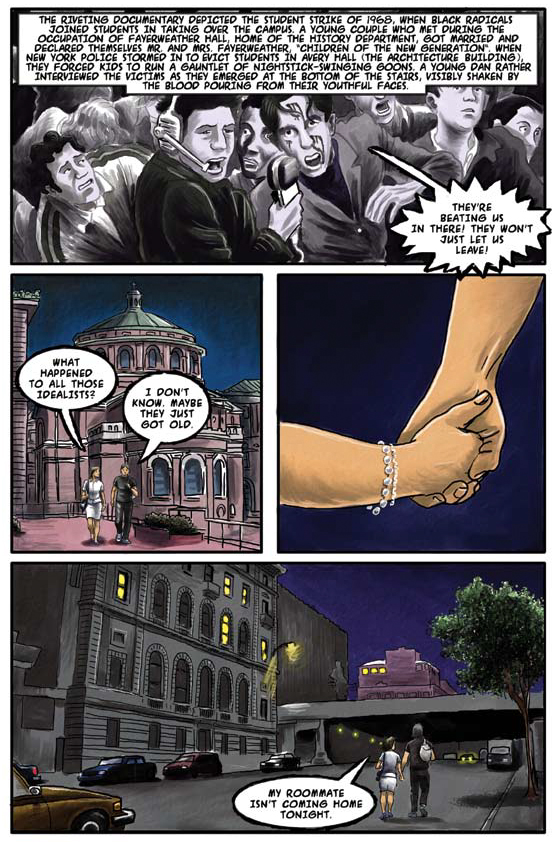

In 2009 I published “The Year of Loving Dangerously,” my graphic novel about my anni horribili, 1984-1985. I was expelled from college, fired from my job and evicted from my dorm — and dumped on the streets of Manhattan during a long hot summer in Reagan America. I discovered that sex wasn’t just my favorite thing, it was also good for finding a place to crash. Manslut – that was me.

Year was my first book collaboration. I wrote the text. Spanish artist Pablo G. Callejo, best known for “Bluesman,” did the artwork. The results were spectacular: Callejo is a genius and evoked 1980s New York like no one else could.

There was interest in turning Year into a movie. Also a TV show. You know how that goes. I think the time wasn’t right.

Now, however, everything is coming up 1980s. I keep thinking someone should make a movie or TV show out of it. Not because I want a movie or TV show, which of course I do, but because it was so fucking cool and would make an awesome adaptation.’

So, smart Hollywood peeps, if you’re out there, here’s a few pages. If you want to see the whole thing, ping me by hitting the Contact tab on Rall.com.

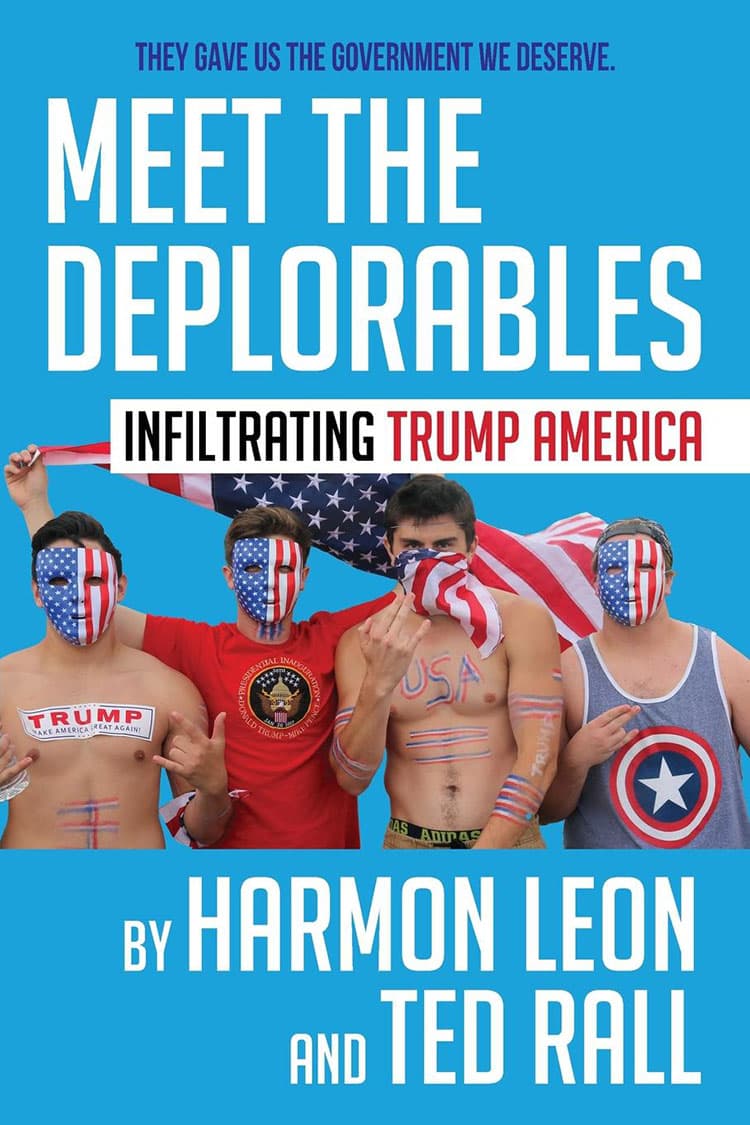

Perfect for the Holidays! Order a Signed Copy of “Meet the Deplorables”

I am now offering signed copies of “Meet the Deplorables” dedicated to you or anyone you want. It’s a beautiful, full-color hardback book I co-authored with Harmon Leon. He infiltrated weird alt-right organizations like the Minutemen; I did the political analysis and the cartoons. Click the button below:

Meet the Deplorables: Infiltrating Trump America

Publication Date: December 12, 2017

Order at Indiebound!

Order at Amazon!

Order at Barnes and Noble.

Legendary infiltration journalist Harmon Leon is at it again, this time teaming up with ferocious political cartoonist Ted Rall answer the question most of America has been asking: “What the hell happened in 2016?” In their new book, Meet the Deplorables: Infiltrating Trump America, Leon goes deep undercover into the heart of Trump America, and Rall–two-time winner of the RFK Journalism Award and a Pulitzer Prize finalist–adds an innovative extra dimension to the book with his own essays and full-color cartoons.

Running throughout Meet the Deplorables, Rall’s distinctive artwork enhances the insightful and often irreverent tone employed by Leon–an award-winning New York journalist whose stories have appeared in VICE, Esquire, The Nation, and National Geographic. In his inimitable Gonzo-style, Leon’s carefully crafted narrative is designed to help us understand (and humanize) the “deplorables,” a word used by Hillary Clinton during the 2016 campaign to describe the racist, sexist, homophobic, and xenophobic supporters of Donald J. Trump.

For the sake of humor and satire, Leon ventures where elite coastal journalists dare not: deep into Red State territory, where his audacious accounts vicariously take readers on a journey of enlightenment by providing a fresh and first-hand perspective of right-wing subcultures and those most adversely affected by Trump’s appalling policies on immigration, healthcare reform, and race relations. His exploits include:

– visiting an anti-Muslim hate group during the height of Islamophobia

– knocking door-to-door as a canvasser for the Trump campaign

– joining a conversion therapy group that tries to “turn” homosexuals straight

– attending a gun store wedding where couples seal vows by firing assault rifles

– watching fanatics receive free Trump tattoos

– participating in a Christian purity ring ceremony in Ohio.

This unique collaboration between the formidable team of Harmon Leon and Ted Rall holds up a mirror to modern conservative life and reflects a reality that is outrageous, entertaining, and always illuminating.

Current Events/Biography, 2017

39 West Press Hardback, 6″x9″, 240 pp., $27.95

To Order A Personally Signed Copy directly from Ted:

Pre-Order “Meet the Deplorables” Now!

My new book with Harmon Leon doesn’t come out until the 12th but you can pre-order it now!

Barnes and Noble: click here.

IndieBound: click here.

Amazon: TBA

I promise, if you’re into my stuff you’ll love Harmon’s writing and take on things too. This is a great collaboration.

FYI advance orders have a big impact on a book’s success, and thus are a big help. Also, think of the children! This makes a great holiday gift for the Trump hater or lover in your life.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Will President Trump Last Another Year?

Some political experts doubted that Donald J. Trump would tough it out this long. This, after all, was a very strange man, possibly afflicted by obsessive-compulsive disorder to the point that he even floated the idea of staying in New York.

He moved to Washington. But Trump’s dangerous old compulsions remain: Twitter diarrhea. Impulsiveness. Recklessness. He insults adversaries whose cooperation he needs. He’s allergic to compromise. Will these character defects destroy him politically in 2018?

The odds of Trump remaining president by the end of next year, I said recently, were significantly less than 50%. I still think that’s true. But as noted above, we have a tendency to underestimate this highly inestimable man. The will-Trump-survive question is an equation with many variables.

One thing is clear: “The Resistance,” as the left-center political forces aligned against Trump and the Republicans grandiosely call themselves, is a null force. If Trump is forced out of office, it won’t have much to do with these Hillary Clinton supporters. The Resistance’s street activism peaked out with the Women’s March on January 21, 2017. They are, in Trumpspeak, Losers.

Russiagate, the allegation that Putin’s government “hacked the election” for Trump, still hasn’t risen above the level of a 9/11 Truther conspiracy theory — not one iota of actual evidence has appeared in the media. (Sorry, so-called journalists, “a source in the intelligence community believes that” is not evidence, much less proof.)

But Russiagate led to the appointment of special counsel Robert Mueller. Mueller’s sweeping powers and authority to pursue any wrongdoing he finds regardless of whether or not it’s related to Russian interference with the 2016 presidential election has already led to the downfall and flipping of ex-Trump national security advisor Michael Flynn.

Mueller’s pet rats may never turn up a smoking-gun connection between Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump. But they likely know where Trump’s bodies are buried. In addition to obstruction of justice — to which Trump de facto pled guilty in one of his insipid tweets — charges related to sleazy business dealings are a strong possibility. Was/is Trump in deep with Russian oligarchs and corrupt government officials? Perhaps not — but he’s an amoral real estate developer who follows money wherever it leads, including authoritarian regimes where transparency is nonexistent.

Behind every great fortune, Balzac wrote, there is a crime. Trump’s cash hoard probably results from many more than a single illegal act.

Impeachment or resignation? Having researched Trump for my 2016 biography, Trump is more likely to give away his fortune to charity than slink away in a Nixonian resignation. His ego is too big; he’s too pugnacious. He’d rather get dragged out kicking and screaming — unless it’s part of a deal with Mueller or other feds to avoid prosecution.

So impeachment it would need to be.

But no political party in control of both houses of Congress has ever impeached a sitting president of its own party. And there’s another powerful countervailing force protecting Trump from impeachment: Republicans’ self-preservation instinct.

GOP lawmakers suffered devastating losses in the 1974 midterm election following Nixon’s near-impeachment/resignation. Democrats did OK in 1998, after Bill Clinton was impeached — but that was an outlier impacted by the biggest boom economy ever.

In the long term, the Republican Party would probably be better off without Trump. But Congressmen and Senators live in the here and now. Here and now, or more precisely in 2018, Republicans know that many of them would lose their jobs following a Trump impeachment.

Despite those considerations, I think that, in the end, House Speaker Paul Ryan, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and other top Republicans are more likely to calculate that pulling the impeachment trigger is worth the likely losses in the fall.

Reason #1 is personal: Paul Ryan’s presidential ambitions. As I speculated in February, I believe Ryan wants to be president in 2020. As Speaker of the House, he’s the one person who can launch impeachment proceedings. I can easily imagine the following quid pro quo: Ryan gets rid of Trump, Pence agrees not to run in 2020, Ryan runs with Pence’s endorsement. Reason #2 is meta: to save the Republican Party as Ryan and McConnell know it. Here’s what I said in February: “Becoming the party of impeachment at a time when impeachment is popular transforms crisis into opportunity, allowing Republicans to cleanse their Trump-era sins (trying to repeal the increasingly well-received Obamacare, paying for the Great Wall of Mexico with deficit spending, etc.) and seize the moral high ground in one swoop. Vice President Mike Pence takes the helm, steadies the ship, promotes their right-wing agenda with more grace than his former boss, and Ryan and his buddies prepare for 2020.”

If anything, the GOP is in bigger trouble now.

Trump’s approval ratings hover between 35% and 40%. More worrisome for him and the Republicans, his support is shaky while those who hate him are firmly entrenched in their beliefs.

Approval of the Republican Party has hit 29%, the lowest ever recorded.

After failing to repeal Obamacare, the Republicans finally scored their first legislative victory last week when the Senate passed a sweeping series of tax cuts — but it’s wildly unpopular (52% against, 25% for). Pyrrhic much?

GOP elders were already fretting that Trump was ruining the GOP brand following the alt-right riots in Charlottesville. What they’re about to realize (if they haven’t already) is that the president has also undermined one of the party’s strongest longstanding arguments: “The government should be run like a great American company,” as Jared Kushner said in March. “Our hope is that we can achieve successes and efficiencies for our customers, who are the citizens.”

Voters have watched Trump’s staff churn through one resignation and shakeup after another, the president diss his own sitting cabinet members, with no sign of his campaign’s stated goals being talked about, much less executed. The Trump Administration has been characterized by communication breakdowns, chaos, mismanagement and waste — and has little to show for its efforts.

This is the current face of the Republican Party: corrupt, stupid and inept. Ryan and McConnell know they must disassociate the GOP from Trump.

They have to destroy their party in order to save it.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall) is co-author, with Harmon Leon, of “Meet the Deplorables: Infiltrating Trump America,” an inside look at the American far right, out December 12th. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

My New Book Comes Out in 6 Days!

So Harmon Leon is a friend, colleague, stand-up comic and, most famously, an infiltrator. He went undercover into weird alt-right spaces to get the dish about Trump America…and the results are hilarious! “Meet the Deplorables” includes Harmon’s infiltrations, my cartoons and my political analysis…and even some hope for the near future. Available December 12th. Order info available soon.

There will also be a book tour.

More info here.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Trump, the Pussy Tape and a Bunch of Lazy Journalists

“The tape, without question, is real.”

“The tape, without question, is real.”

I expected better from The New York Times.

The quote is the lede of a news story by Daniel Victor, a reporter at the Times. Victor’s piece is about a controversy, or more precisely, an echo of a controversy: the 2005 “Access Hollywood” recording in which Donald Trump is heard joking with show host Billy Bush about grabbing women’s genitals. The audio (you don’t see Trump’s face during the gutter talk) was released shortly before a major debate against Hillary Clinton; it nearly cost Trump the election.

Perhaps in an effort to distance himself from the big sexual harassment discussion, Trump has lately been telling people that the audio wasn’t real — that it wasn’t him saying all that sexist stuff. “We don’t think that was my voice,” he told a senator recently.

Trump’s denial-come-lately (he apologized at the time) is being ridiculed. “Mr. Trump’s falsehoods about the ‘Access Hollywood’ tape are part of his lifelong habit of attempting to create and sell his own version of reality,” Maggie Haberman and Jonathan Martin of the Times wrote. Senator Jeff Flake said: “It’s dangerous to democracy; you’ve got to have shared facts…that was your voice on that tape, you admitted it before.”

Trump lies a lot. He may be lying here. I don’t know.

The point is, neither does The New York Times.

What disturbs me more than the possibility/likelihood that the president is a liar is the fact that journalists who ought to know better, including six-figure reporters employed by prestigious media organizations like The New York Times that repeatedly brag about adhering to high standards, are too lazy and/or ignorant to conduct basic due diligence. This isn’t new: I have been the subject of news articles for which the news outlet didn’t call me for comment (calling for comment is journalism 101). But journalistic laziness is still shocking and wrong.

A news article that begins with an unambiguous declarative statement like “The tape, without question, is real” ought to contain proof — or at least strong evidence — that there really is no question.

Victor’s piece does not come close to meeting basic journalistic standards. Victor quotes a host from “Access Hollywood” who says that’s Trump on the tape. Mostly he relies on Trump’s 2016 apology: “I said it, I was wrong, and I apologize.” But so what? I can say I was on the grassy knoll but that doesn’t mean I really shot JFK.

I don’t like Trump either. But it’s reckless and irresponsible to report as news, as proven fact, something that you don’t know for certain.

The sloppy reporting about the authenticity of the Trump tape reminds me of the breathtaking absence of due diligence exercised by The Los Angeles Times when it fired me as its cartoonist. There too the story centered on an audio.

I wrote in a Times online blog that an LAPD cop had roughed me up and handcuffed me while arresting me for jaywalking in 2001. The police chief gave the Times’ publisher an audio the cop secretly made of the arrest. The audio was mostly inaudible noise, yet the Times said the fact that it didn’t support my account (or the officer’s) proved I had lied. I had the audio “enhanced” (cleaned up); the enhanced version did support my version of events. Embarrassed and/or scared of offending the LAPD (whose pension fund owned stock in the Times’ parent company, Tronc), the Times refused to retract their demonstrably false story about my firing. I’m suing them for defamation.

Where my former employer went wrong was that they didn’t investigate thoroughly. They were careless. They didn’t bother to have the audio authenticated or enhanced before firing me and smearing me in print.

Back to the Trump tape.

Editors and reporters at any newspaper, but especially one the size of the New York Times, which has considerable resources at its disposal, ought to know that proper reporting about audio or video requires both authentication and enhancement.

Proper forensic authentication of a recording like the “Access Hollywood” recording of Trump is a straightforward matter. First, you need both the original tape as well as the device with which it was made. A copy or duplicate of an audio or video cannot be authenticated. The tape and recording device are analyzed by an expert in a sound studio for signs of splicing or other tampering. The identity of a speaker can never be 100% ascertained, but comparisons with known recordings of voices (as well as background noise from the original recording location) can provide meaningful indications as to whether a recording really is what and who it is purported to be. (The LA Times didn’t do that in my case. Anyway, they couldn’t. All they had was a copy, a dub — and you can’t authenticate a copy.)

My situation with the LA Times highlights the importance of enhancement. Had the paper’s management paid for a proper enhancement, they would have heard what lay “beneath” a track of wind and passing traffic: a woman shouting “Take off his handcuffs!” at my arresting officer.

Do I believe Trump’s denials? No.

Is the media right to say Trump is lying about the Billy Bush recording? Also no.

Because the media have offered no evidence as to the recording’s authenticity. For all we know, the original tape was never released. I’d be shocked if the recording device was released. And I’d be triple-shocked if those two items were sent to a professional audio expert for authentication.

A president who is an evil, dimwitted, underqualified megalomaniac is a danger to democracy.

So is a lazy, cheap, cut-and-paste class of journalists who don’t bother to thoroughly investigate stories.

(Ted Rall’s (Twitter: @tedrall) next book is “Francis: The People’s Pope,” the latest in his series of graphic novel-format biographies. Publication date is March 13, 2018. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

Ted Rall v. LA Times et al. – Lawsuit Update

Remember this the next time someone tells you it’s too easy to file a lawsuit in American courts. We need tort reform, but not to make it harder. It needs to become easier to seek justice!

As I wrote earlier, a judge in LA Superior Court ruled against me in the first round of anti-SLAPP motions filed against me by the LA Times. The Times is deploying anti-SLAPP — a law promoted as a way to protect whistleblowers and critics against wealthy corporations — against me because I am suing them for defamation and wrongful termination. (This was after they falsely claimed I had lied about being roughed up by an LAPD police officer in the course of a jaywalking arrest, and continued to lie after I used their own evidence to prove it. The Times and its publisher had a close financial and political relationship with the LAPD, which I had repeatedly criticized in my cartoons.)

On November 20 the ethics-impaired LA Times — terrified that my case might someday be heard before a jury of my peers — continued its scorched-earth litigation tactics and asked a judge to issue a judgement against me for about $350,000 of the Times’ legal fees. The fees included Times lawyer Kelli Sager’s $705/hour fee, which she described as “discounted.” It also included fees for preparing the anti-SLAPP motions themselves, which violated court rules by running 27+ pages instead of the allowed 15, and a previous judge threw out of court.

The Times also requested that I be forced to post an “appeals bond” equal to 1.5 times the value of the award, thus amounting to about $525,000. That bond would have to be posted in cash; in other words, I would need to send a bonding company 100% ($525,000) to post the bond in order to continue my case.

Remember: the Times is the defendant! They wronged me, not the other way around.

The judge ruled in the Times’ favor.

Corporate media takes care of its own, so I do not expect much solidarity from my fellow inked-stained wretches.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Sexual Harassment and the End of Team Politics

Until the 1990s, American electoral politics were divided ideologically, between the opposing ideas of liberalism and conservatism. Now we have Team Politics: Democrat versus Republican, my party right or wrong.

Back then, Rush Limbaugh sometimes accused the Republican Party of betraying conservative principles. At the same time, the liberal op-ed writers at the New York Times occasionally took the Democratic Party to task for not being liberal enough.

Those things don’t happen now. Americans back their party the same way they back their favorite sports team — with automatic, stupid loyalty.

If you are a liberal, you support the Democratic Party no matter what. You vote for Democrats who vote for Republican wars of choice. You look the other way when they do things that only Republicans should do, like order political assassinations and regime change. You even make excuses for outright betrayal, like when Bill Clinton signed NAFTA and welfare reform.

If you are a conservative, you support the Republican Party no matter what. You vote for Republicans who drive up the deficit with unnecessary spending. You look the other way when they do things that only Democrats should do, like allowing the NSA to violate basic privacy rights and failing to put America first when it comes to foreign trade. You even make excuses for outright betrayal, like when “family values” Republicans wallow in sexual impropriety.

Never have team politics been more evident than in the current tsunami of sexual harassment scandals. Republicans make excuses for their politicians, like Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore and former Fox News star Bill O’Reilly, even when they are credibly accused of sexual assault. Most notably with Bill Clinton but arguably continuing with big-time democratic donor Harvey Weinstein and perhaps Al Franken, Democrats do the same.

I can’t predict whether this national conversation on sexual harassment will yield the ideal result, a widespread cultural consensus that no means no and that workplaces should be desexualized. It seems clear that permanent positive change is in the making. This moment should certainly mark the beginning of the end of silly Team Politics.

It would go too far to argue that Harvey Weinstein got a free pass for so many years despite his hideous behavior including alleged rape, solely because he donated millions of dollars to the Clintons and the Democrats, and hosted lavish fundraisers at his home for top Democrats like Barack Obama. But Weinstein’s high rank in Team Democrat was part of it.

And it was pretty much the whole deal for Bill Clinton. Sexual harassment and assault charges against the then-Arkansas Governor were swept aside by Democratic voters in 1992. After four years of the clueless George H.W. Bush, whose economic policies prolonged a deep recession, neither liberal voters nor liberal pundits nor the corporate Democrat classes were going to let Bill’s “bimbo eruption” stand in the way of a change. Even after the Monica Lewinsky scandal — if Louis C.K. lost jobs because he abused his “power” over fellow comedians, how about the power gap between a President of the United States and a 21-year-old intern? It was just a blow job, after all.

You may have forgotten: MoveOn.org got its name from those who wanted to “move on” past the Clinton impeachment. Nothing to see here, folks!

Give (a few) liberals credit. Some are finally giving Clinton accuser Juanita Broaddrick the fair consideration she never got in 1999, when she said the future president had raped her in 1978.

ABC News reporter Sam Donaldson, known for his aggressiveness, admitted at the time that “people in charge of our coverage, at managing editor status, have not seen this as a story they wanted to spend a lot of time on…lots of people argued that it was unseemly.” Better 18 years late than never — at age 74, Broaddrick is lucky to have lived long enough to see her story discussed (albeit not deeply or at length).

Democrats who claimed to be feminists yet ignored Clinton’s misogyny feel sheepish and hypocritical. As they should. So they’re mostly keeping quiet and hoping for a change in subject. Which they shouldn’t. At least there’s a chance they won’t reflexively resort to the empty tribalism of Team Politics the next time one of “theirs” faces similar allegations. (Hello, Representative John Conyers.)

Now it’s the Republicans’ turn to come to Jesus.

Yeah, Mitch McConnell says Roy Moore isn’t fit to serve in the Senate. But that means nothing; McConnell didn’t like Moore in the first place. Trump is the head of the Republican Party — and the president is still tacitly endorsing Moore, and might even campaign in person for the alleged child molester.

Better a pedophile than a Democrat, Trump argues insanely. But kneejerk support for a GOP candidate this repugnant, as even most Republicans can plainly see, is Team Politics having jumped the shark and then some.

Die, Team Politics!

Let’s Make the Ideological Divide Great Again.

(Ted Rall’s (Twitter: @tedrall) next book is “Francis: The People’s Pope,” the latest in his series of graphic novel-format biographies. Publication date is March 13, 2018. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)