Right-wingers conflate nationalism with patriotism. But they’re not the same thing. Patriots love their country because it does good things; for nationalists it’s our country right or wrong. A lot of stuff nationalists call patriotic couldn’t possibly be more un-American.

The singing of the national anthem before sporting events, and the reciting of the Pledge of Allegiance, are prime examples.

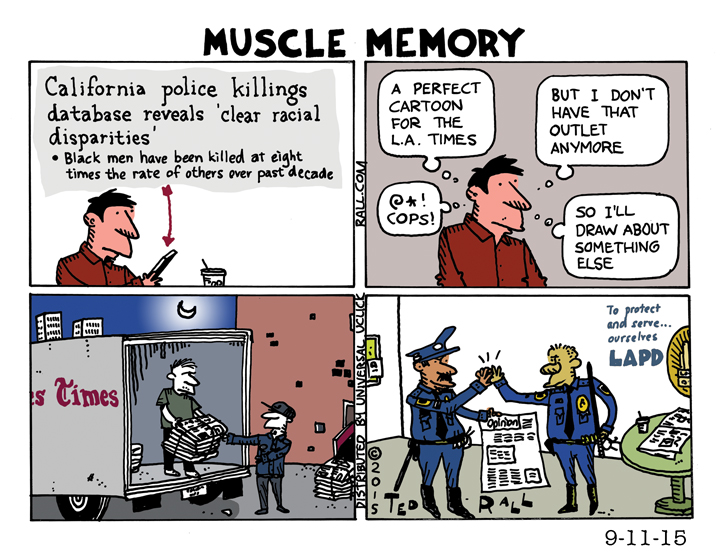

The latest nationalism vs. patriotism controversy arrives courtesy of Colin Kaepernick, the African-American pro football player blackballed by the NFL for kneeling in silent protest over police shootings of blacks rather than stand for the signing of the national anthem alongside his teammates and fans before games. The “take a knee” movement has spread throughout the league, largely in response to President Trump’s crude remark that those who refuse to stand during “The Star Spangled Banner” are “sons of bitches.”

At football games and similar events where the anthem is sung, standers far outnumber kneelers — and that’s weird. Because if one person is kneeling against police brutality, then it stands to reason that standing up means you support cops gunning down unarmed black people. Are there really that many racists?

That, and when you stop to think about it, the whole idea of rote rituals to prove our loyalty run completely counter to what most Americans, liberal or conservative, think their country is about.

As I have written before, lefties and righties don’t have the same ambitions for the U.S. Following the tradition of the French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, the Left idealizes individual rights. They dream of a country where everyone is not only created equal, but treated accordingly. The Right values empire. Rightists’ ideal America is a global military and economic superpower.

Still, the two sides have something in common. They want to be left alone, to live their lives as free of government interference as possible. Progressives want the government out of their bedrooms. Traditionalists want it out of their incomes. Totalitarianism — a form of government whose control over citizens’ daily lives leads to the requirement that everyone attend one meeting after another and report dissent to the authorities — could no more catch on here than North Korean-style displays of signs flipped by synchronized flags or parades of military hardware (though Trump wants to start those).

Like the singing of the anthem at games, the Pledge of Allegiance reflects a totalitarian impulse you find in fascist and authoritarian regimes, not democracies. The U.S. and Canada are the only countries on earth where national anthems are played at the start of sporting events. Even in many authoritarian states, the requirement that children (and athletes) swear fealty to the nation (or, as here, its flag) would be considered too creepy to contemplate.

When your country is crazier than Zimbabwe, it’s time to take stock — even if you’re a Republican.

Other nations require oaths of allegiance from those taking public office, like members of parliament. Some ask the same of foreigners seeking to become naturalized citizens. But the U.S. may be the only nation on earth to have a widely-used pledge of allegiance.

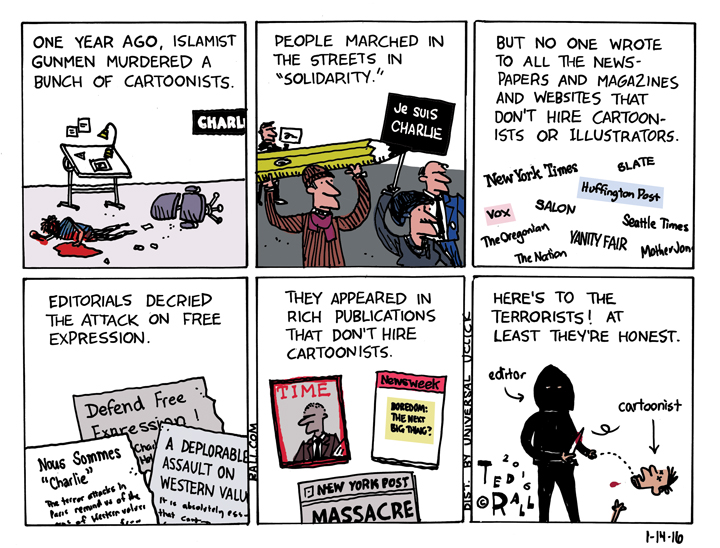

Children who refuse to recite the Pledge of Allegiance are routinely punished, criticized and ostracized, even in public schools. I know — it happened to me in elementary school. Kaepernick, a top-tier athlete, has been denied employment. These are obvious violations of the all-American value of free speech and expression guaranteed by the First Amendment.

The addition of “under God” in 1954, at the height of the McCarthy era and its rancid loyalty oaths, further violates another core principle of Americanism, the freedom to worship as you please or not at all as protected under the Establishment Clause of the US. Constitution.

In one respect, however, the Pledge of Allegiance owes its origins to something that couldn’t be more American: a huckster out to make a few extra bucks.

Why do Americans pledge allegiance to the “flag,” as opposed to the nation or its government? It boils down to capitalist greed. The origins of the Pledge date to 1892, when James B. Upham, the marketing executive of the popular children’s magazine The Youth’s Companion used the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas to promote a conference in honor of the American flag. He pushed the Pledge in his magazine as a way to promote nationalism and sell flags to public schools. Schoolhouses purchased 26,000 flags the first year alone.

Kids reciting the pledge were supposed to raise their arms at the same time — yep, the Hitler “sieg heil” salute before Hitler. World War II put an end to that in American schools.

Having traveled extensively, I have observed that the countries whose governments insist upon the most extravagant displays of nationalism line up neatly with those with the least personal freedom. In authoritarian China and the police state of Turkmenistan, national flags and banners extolling slogans and quotes of the ruling party festoon every government office and pedestrian overpass. As Turkey moves away from democracy and closer to autocracy, Turkish flag stickers multiply on automobiles.

It is the opposite in the European democracies. A Frenchman who hung a French flag from his front porch would be ridiculed by his neighbors, socialist and Le Pen supporter alike. It is not that the French and the Dutch and the Spanish and other Europeans do not love their countries as much as Americans do; if anything, most Europeans are grateful that their countries are not like ours. They are patriots. And they remember World War II, when those who liked to wave flags and insisted on loyalty oaths to the state turned out to be dangerous.

Everyone should sit out the singing of the national anthem. It’s archaic and uncomfortably reminiscent of fascism.

It is time to leave the Pledge of Allegiance where it belongs, on the dungheap of history, remembered as a clever way to move piles of colored cloth.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall) is author of “Trump: A Graphic Biography,” an examination of the life of the Republican presidential nominee in comics form. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

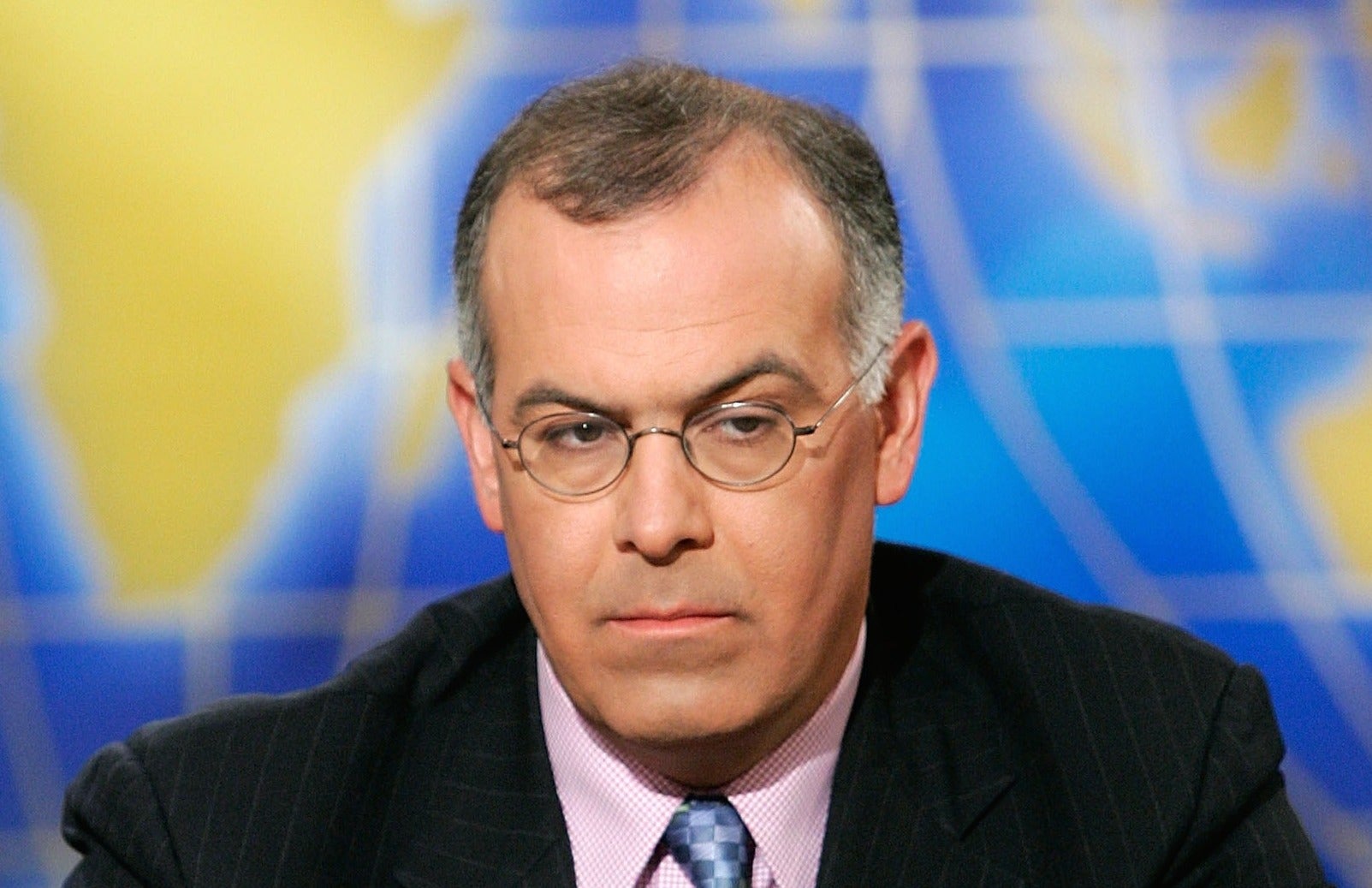

Stipulated: David Brooks isn’t that smart.

Stipulated: David Brooks isn’t that smart.