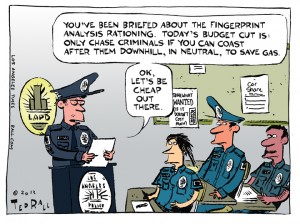

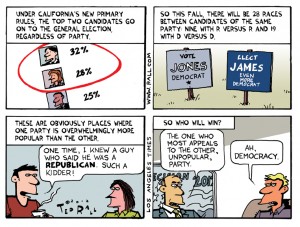

I draw cartoons for The Los Angeles Times about issues related to California and the Southland (metro Los Angeles).

This week: The LAPD has notified cash-strapped police precincts that they may only apply for 10 fingerprint analyses from the crime lab every month. Cases are backing up due to budget cuts. What next in budget-cutting?