On the last couple of blogs I’ve had some negative feedback, no big deal, but I guess I should give some background on myself, I’ve had the advantage or disadvantage, as it may be, of the following. I was born and raised in a white middle class home, not a victim of any childhood abuses or trauma, I attended a state univeristy and got out with zero student loans, I majored in something I thought would be useful, (Education) instead of the more popular French Literature. I joined the military and have been to some of the best and worst places on the planet, I’ve seen acts of incredibly good and out of this world evil, I’ve worked with people that you would be proud to know and others that make your skin crawl, in both Afghanistan and Iraq I’ve seen treatment of women and minorities that would make you physically sick to your stomach. I’m sorry that when I talk about things that might happen in 50 years it’s not as big of concern as when I see kids starving on the street and people killed because of their faith, I don’t have the advantage of sitting in an apartment in American regurgitating the talking points of Moveon, NPR or whomever the flavor of the week is.

Day to day concerns

I have plenty to worry about throughout the day, job security, bill paying, saving for my daughters education all the way down to getting out of work before traffic gets bad, hoping they don’t run out of eclairs at the bakery and keeping my weight in check. I’d say I run the gauntlet of worries and think that I’m pretty average, some stuff is important some stuff not so much but it got me thinking about social issues in America, do people really worry about them?

For example, a lot of right wingers are fervently against gay marriage, you see them in TV interviews, protesting on the streets and talking to you about it whenever they get the chance. I’m curious as to whether or not John and Martha are in bed at night and John looks over and says “Martha I don’t think I can take another day if these fags can get married”. If that is the main worry that these people have then two things jump out at me, they must have their lives so sorted out that they don’t have real worries and secondly I’m jealous.

I’d like to be able to say that the left is better but of course we aren’t, I totally believe in climate change/global warming, it’s hard for me to get concerned though when they say the ocean is going to raise 1/40th of an inch in the next 25 years, it’s kind of a let down and doesn’t really endear you to main stream America. If you have “normal” worries, then the ocean raising tenths of inches doesn’t really jump into my Top 10.

I guess I can see why these worries would be number 1 if you were a gay couple trying to get married or a scientist whose job it was to deal with climate change, but for normal Americans who are struggling with high unemployment and home foreclosures it’s hard to imagine why these issues are such hot button.

My Christmas wish is to find a politician who deals with real US “day to day” worries and not one who panders to our political extremes. I know it makes good television and a lively debate, but I don’t think I’m alone when I say there are more important issues to worry about.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Iran – Because Two Wars Aren’t Enough

Why Doesn’t Anyone Call Out Romney for Warmongering?

Mitt Romney had a barnburner of a weekend in Israel. The GOP nominee apparent shared his unique combination of economic and anthropological wisdom, attributing the fact that Israel’s GDP and average income is many times higher than those of the Palestinian Occupied Territories to Israelis’ superior “culture.”

As if spewing one of the most overtly racist lines in recent presidential campaign history wasn’t enough, eschewing “containment” (read: “diplomacy”), Romney also endorsed a preemptive Israeli military strike against Iran in order to prevent the latter’s nuclear program—Israel’s own, illegal nuclear weapons stockpile is OK since it’s a U.S. ally—from moving forward.

“We have a solemn duty and a moral imperative to deny Iran’s leaders the means to follow through on their malevolent intentions,” Romney said, stating that “no option should be excluded.”

He didn’t say how he knew the intentions of Iran’s leaders. Clairvoyance? Bush had it too.

Though Mitt slightly walked back his campaign’s sabre rattling, the message was clear. If he is elected, Israel will receive a blank check to begin a war against Iran, one of the most well-equipped military powers in the Middle East—a conflagration in which the United States could easily wind up getting dragged into. (In a subsequent interview he reiterated that “we have all options on the table. Those include military options.”)

Most criticism focused on Romney’s flouting of the traditional proscription against candidates questioning a sitting president’s foreign policy while visiting foreign soil. Though, to be fair, the differences between his and President Obama’s approach to Israel and Iran are tonal and minor.

As usual with the U.S. media, what is remarkable is what is going unsaid. Here we are, with the economy in shambles and the public worried sick about it, the electorate tired of 12 years of war against Afghanistan and nine against Iraq, yet Romney—who could be president six months from now—is out ramping up tensions and increasing the odds of a brand-new, bigger-than-ever military misadventure.

Warmongering has gone mainstream. It’s a given.

In a way, Romney’s willingness to risk war against Iran is merely another example, like the car garage and dressage, of how clueless and out of touch he is. Most Americans oppose war with Iran. For that matter, so do the citizens of the country on whose behalf we’d be killing and dying, Israel. But even Romney’s Democratic opponents give him a pass for Romney’s tough-guy act on Iran.

The reason for the somnolent non-response is obvious: it’s nothing new. Year after year, on one foreign crisis after another, American presidents repeatedly state some variation on the theme that war is always an option, that the military option is always on the table. You’ve heard that line so often that you take it for granted.

But did you know that “keeping the military option on the table” is a serious violation of international law?

The United States is an original signatory of the United Nations Charter, which has the full force of U.S. law since it was ratified by the Senate in 1945. Article 51 allows military force only in self-defense, in response to an “armed attack.” As Yale law and political science professor Bruce Ackerman wrote in The Los Angeles Times in March, international law generally allows preemptive strikes only in the case of “imminent threat.” In 1842 Secretary of State Daniel Webster wrote what remains the standard definition of “imminent,” which is that the threat must be “instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means and no moment for deliberation.” The enemy’s troops have massed on your border. They have superior force. What must be done to stop them is evident. There’s no time for diplomacy.

Iran’s nuclear program doesn’t come close to this definition, even from Israel’s standpoint. Bruce Fein, deputy attorney general under Reagan, told Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting’s Extra! Magazine: “It is nothing short of bizarre to claim, as the Obama Administration is doing, that the mere capability to make a bomb is justification for a preemptive attack. That’s a recipe for perpetual war. Almost any country could have the capability to make a bomb. They are torturing the word ‘imminent’ to the point that it has no meaning.”

By endorsing an Israeli attack against Iran at a time when there is no proof that Iran has nuclear weapons, intends to develop them, or use them if it does, Romney is going farther than Obama, who has engaged in back-channel diplomacy.

The Allies’ main brief against the Nazi leaders tried at Nuremberg was not genocide, but that they had violated international law by waging aggressive war. Yet every American president has deployed troops in aggressive military actions.

Aggressive war hasn’t been good for America’s international image, the environment, our economy or the millions who have died, mostly for causes that are now forgotten or regretted. But unless we draw the line against reckless, irresponsible rhetoric like Romney’s, it will go on forever.

(Ted Rall’s new book is “The Book of Obama: How We Went From Hope and Change to the Age of Revolt.” His website is tedrall.com. This column originally appeared at NBCNews.com)

(C) 2012 TED RALL, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

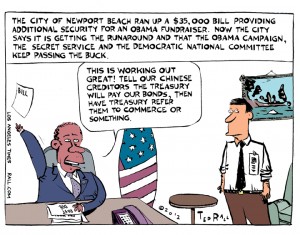

LOS ANGELES TIMES CARTOON: A California Town Gets The Runaround

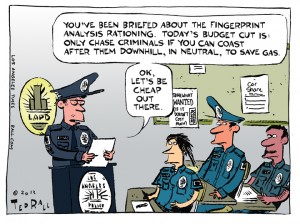

I draw cartoons for The Los Angeles Times about issues related to California and the Southland (metro Los Angeles).

I draw cartoons for The Los Angeles Times about issues related to California and the Southland (metro Los Angeles).

This week: The city of Newport Beach ran up a $35,000 bill providing additional security for an Obama fundraiser. Now the city says it is getting the runaround and that the Obama campaign, the U.S. Secret Service, and the Democratic National Committee keep passing the buck.

Ted’s well written case against war is doomed

I consider Ted a friend and agree with a good portion of what he’s written, unfortunately for him and the rest of us, his case against Iran is useless. Ted wrote a informative, well researched and thought provoking paper, too bad he missed the majority of voters…..here is the reaction in Kansas and how the Republicans will get their war.

Reaction to Ted “Ugh this paper is nearly a page long and he’s from NY….yawn”

Romney-“9/11, Muslim, Terrorists, High gas prices”

Done and done.

The war personally (troops/veterans) make up less than 1% of the population, there will be no WWII style rationing, most people will never travel to Iran or meet an Iranian as well as never befriend a US soldier. I’m a former veteran and I’ve never met a group of people (not all but the majority) that were so rah rah for the cause that they refuse to believe anything outside of the Army vision, most Americans want to believe in the good of the US government anything outside of that would cause their world to come crashing down.

NBCNews.com Blog: Calling Romney out for his warmongering on Iran

In this week’s blog/column, I discuss the media’s silence on the biggest gaffe Romney made—warmongering against Iran.

Why not Mitt?

First off, I’m not a fan of Romney but I’ve been alive for 5 presidents, Reagan, Bush, Clinton, Bush/Gore and Obama. My point is has anything changed? I mean since Reagan don’t we still have an incredible high prison population, shitty schools, too many people needing food stamps, rampant underemployment and every other social ill we can think of? If Mitt wins the presidency isn’t it just another rich white guy running the country? My more liberal friends are up in arms over the fact that he might win but really would anything change?

@Whimsical

This is guest blogger Susan Stark.

Several years ago, Mr. Rall gave me the privilege of blogging on his site. I’ve never used this privilege to address a commenter, but I think I will deviate from this by addressing everyone in general and Whimsical in particular. Here I will quote him:

“An intelligent, realistic column that doesn’t unnecessarily bash Obama and the Democrats for things beyond their control? One that I can agree with every word of?

Who are you, and what have you done with the real Ted?”

Close quote.

Well, I’d like to respond to these assumptions by pointing out a few facts.

Firstly, Ted does not *unnecessarily* bash Obama and the Democrats. Ted is a pundit and a political cartoonist. It is his job to criticize those in power, no matter what political party, when they deserve it.

Secondly, Whimsical, why is Ted “intelligent” and “reasonable” only when you agree with him? It may shock you to know that I don’t always agree with Ted, yet I still think him intelligent and reasonable even when I don’t. The main reason why I’ve read Ted for 12 years is his ability to think outside of the box; to come up with angles on a story that I and others might not see.

Thirdly, Whimsical, in case you haven’t noticed, not every article Ted has written in the past four years has about Obama and the Democrats. Contrary to what you might think, Mr. Rall doesn’t lay awake at night obsessing about how he is going to “bash Obama” the next day. And I would worry about his sanity if he did.

Fourthly, Whimsical, you state that Ted blames Obama and the Democrats for things “beyond their control”. Well, this begs the question: What exactly do the Democrats and Obama have “control” over? Anything at all? Because if the Democrats are THAT powerless to affect any meaningful change, even when they have a majority of seats in Congress, even when they have one of their own in the White House, then it does absolutely no good to either vote Democratic or support the Democratic party in any way. Yes, you can keep voting Democratic. You can give your blood, sweat and tears to the Democratic Party. You can sacrifice your firstborn child to the Democratic Party. But the result will remain the same: The Democratic Party will be powerless to affect any meaningful change.

Getting back to your last sentence, Whimsical. Where is the real Ted and what have you done with him? Answer: The real Ted Rall is a person who can think outside of the box and give criticism (and credit) where it is due. However, you seem to think that Ted should become a type of informal spokesman for the Democrats. The trouble with that is that the newssphere is so saturated with Democratic shills that one more would break the camel’s back, I’m afraid.

But, of course, that’s not to say that Ted would *never* become a Democratic shill. He *could* decide to do that. But if he did, I would hazard that he would have the self-respect to demand to be paid through the nose and be granted his own cable news show on a major network like CNN or MSNBC. And why not? It worked for Al Sharpton, didn’t it?

Soooo, Whimsical, are you in a position to pay Ted up to his hair-line with filthy lucre and give him his own show on a major news network? Because that’s what it’s going to take to make him see things your way.