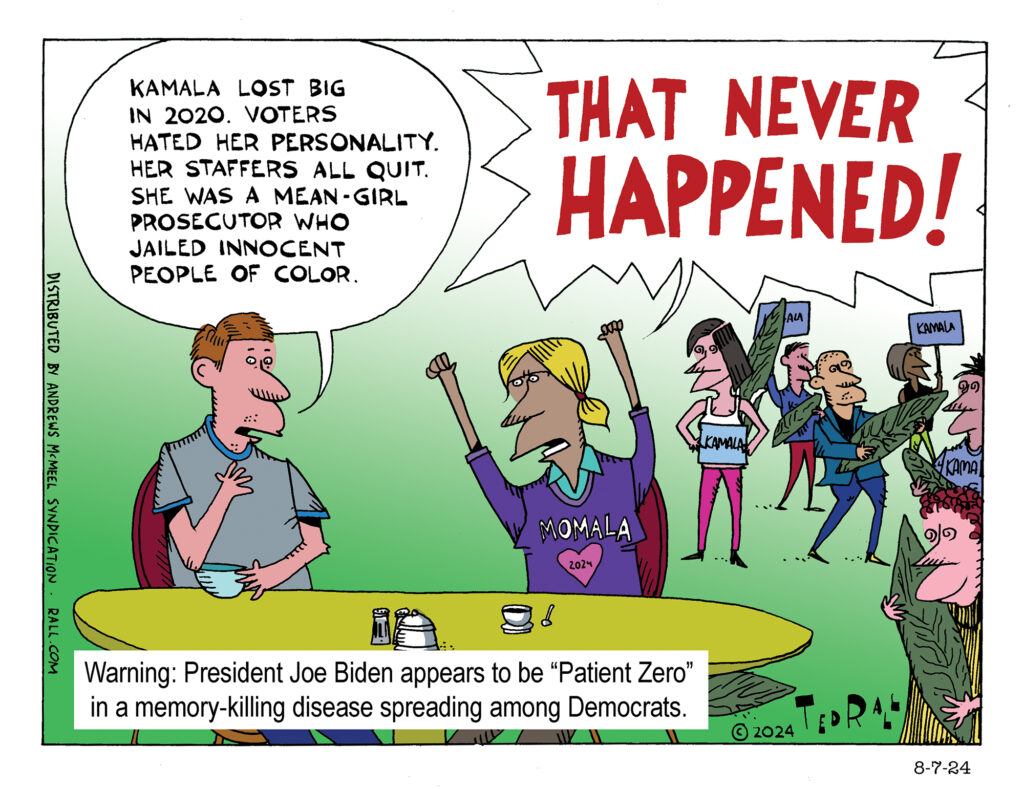

In their relief and excitement about getting rid of Joe Biden as their nominee, Democrats are forgetting all about Kamala Harris’ demonstrated weaknesses as a candidate in the most recent election cycle.

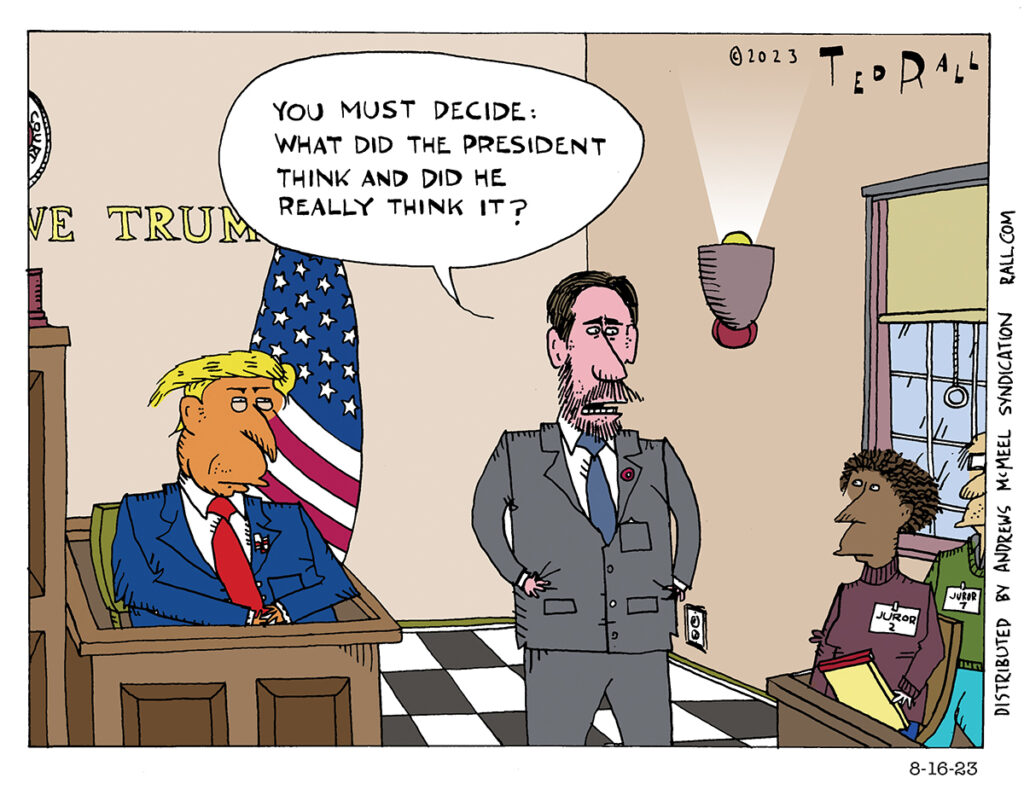

What, If Anything, Did the President Think?

During the Watergate scandal, a recurring question was asked: What did President [Nixon] know and when did he know it? Special Counsel Jack Smith’s January 6th-related charges against Donald Trump prompt a similar question, albeit one that is fundamentally unknowable. If he truly believed that Biden cheated him out of the 2020 election, his efforts to reverse the results were nothing of the sort, but merely his attempt to set things right.

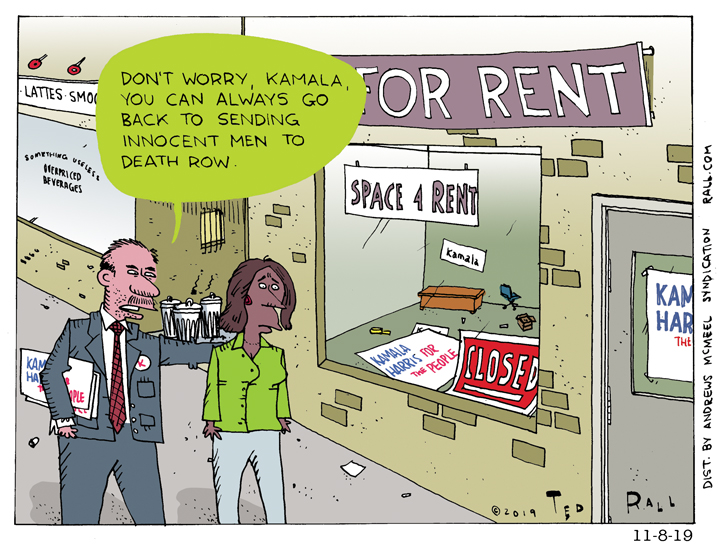

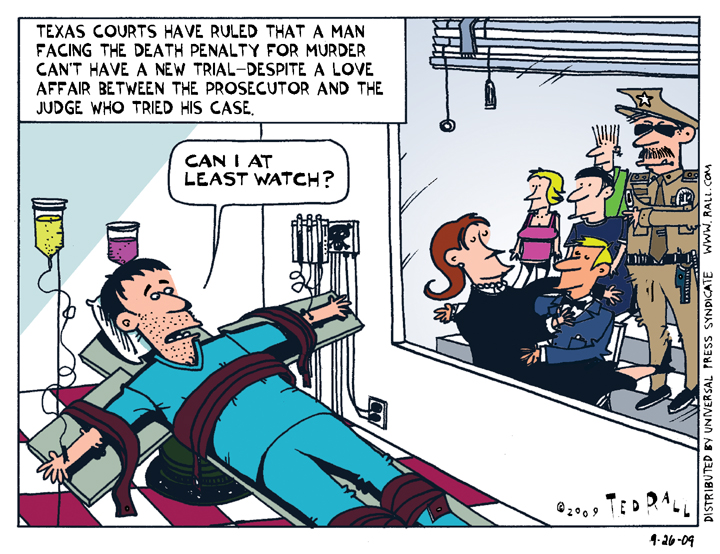

For Kamala Harris, It Looks like It’s Pretty Much the End

Early in the Democratic campaign for president in 2020, former prosecutor and California senator Kamala Harris looked like she was up and coming. Her high point was challenging Joe Biden at a debate about his previous opposition to court-ordered busing in the early 1970s. Soon it became clear, however, that she was more of a troll than a real candidate with real issues. Even though the corporate media didn’t talk about it much, progressive Democrats didn’t have much use for the news that she had deliberately sent an innocent man to death row and then not wanted to talk about it afterwards. Now she is closing offices and laying off staff. Looks like the beginning of the end.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Murder by Prosecutor

Time to Roll Back Excessive Prison Sentences

If you’re looking for sympathy, it helps to be white, male and media-savvy. Throw in charm and brains—especially if your smarts tend toward the tech geek variety—and your online petitions will soon collect more petitions than campaigns against kitten cancer.

These advantages weren’t enough to save Aaron Swartz, a 26-year-old “technology wunderkind” who hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment on January 11. But they did elevate his suicide from that of a mere “data crusader,” as The New York Times put it, to “a cause” driven by millennial “information wants to be free” bloggers and sympathetic writers (whose corporate media overlords would go broke if people like Swartz got their way).

Swartz, who helped invent RSS feeds as a teenager and cofounded the link-posting social networking site Reddit, was a militant believer in online libertarianism, the idea that everything—data, cultural products like books and movies, news—ought to be available online for free. Sometimes he hacked into databases of copyrighted material—to make a point, not a profit. Though Swartz reportedly battled depression, the trigger that pushed him to string himself up was apparently his 2011 arrest for breaking into M.I.T.’s computer system.

Swartz set up a laptop in a utility closet and downloaded 4.8 million scholarly papers from a database called JSTOR. He intended to post them online to protest the service’s 10 cent per page fee because he felt knowledge should be available to everyone. For free.

JSTOR declined to prosecute, but M.I.T. was weasely, so a federal prosecutor, U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz of Boston, filed charges. “Stealing is stealing, whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars. It is equally harmful to the victim whether you sell what you have stolen or give it away,” she told the media at the time.

Basically, I agree. As someone who earns a living by selling rights to reprint copyrighted intellectual property, I’ve seen the move from print to digital slash my income while disseminating my work more widely than ever. Info wants to be free is fine in theory, but then who pays writers, cartoonists, authors and musicians?

I also have a problem with the selective sympathy at play here. Where are the outraged blog posts and front-page New York Times pieces personalizing the deaths of Pakistanis murdered by U.S. drone strikes? Where’s the soul-searching and calls for payback against the officials who keep 166 innocent men locked up in Guantánamo? What if Swartz were black and rude and stealing digitized movies?

But what matters is the big picture. There is no doubt that, in the broader sense, Swartz’s suicide was, in his family’s words, “the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach”—a system that ought to be changed for everyone, not just loveable Ivy League nerds.

Swartz faced up to 35 years in prison and millions of dollars in fines. The charges were wire fraud, computer fraud and unlawfully obtaining information from a protected computer.

Thirty-five years! For stealing data!

The average rapist serves between five and six years.

The average first-degree murderer does 16.

And no one seriously thinks Swartz was trying to make money—as in, you know, commit fraud.

No wonder people are comparing DA Ortiz to Javert, the heartless and relentless prosecutor in Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables.”

As Swartz’s lawyer no doubt told him, larding on charges is standard prosecutorial practice in everything from traffic stops to genocide. The idea is to give the DA some items to give away during plea negotiations. For defendants, however, this practice amounts to legal state terrorism. It can push psychologically delicate souls like Swartz over the edge. It should stop.

It also undermines respect for the law. As a young man I got arrested (and, thanks to a canny street lawyer, off the hook) for, essentially, riding in the same car as a pothead. Among the charges: “Not driving with a valid Massachusetts drivers license.” (Mine was from New York.) “Don’t worry,” the cop helpfully informed me, “they’ll drop that.” So why put it on? Neither the legalistic BS nor the missing cash from my wallet when I got out of jail increased my admiration for this morally bankrupt system.

The really big issue, however, is sentencing. The Times’ Noam Cohen says “perhaps a punishment for trespassing would have been warranted.” Whatever the charge, no one should go to prison for any crime that causes no physical harm to a human being or animal.

Something about computer hackers makes courts go nuts. The U.S. leader of the LulzSec hacking group was threatened with a 124-year sentence. No doubt, “Hollywood Hacker” Christopher Chaney, who hacked into the email accounts of Scarlett Johansson and Christina Aguilera and stole nude photos of the stars so he could post them online, is a creep. Big time. But 10 years in prison, as a federal judge in Los Angeles sentenced him? Insanely excessive. Community service, sure. A fine, no problem. Parole restrictions, on his Internet use for example, make sense.

Sentences issued by American courts are wayyyy too long, which is why the U.S. has more people behind bars in toto and per capita than any other country. Even the toughest tough-on-crime SOB would shake his head at the 45-year sentence handed to a purse snatcher in Texas last year. But even “typical” sentences are excessive.

I won’t deny feeling relieved when the burglar who broke into my Manhattan apartment went away for eight years—it wasn’t his first time at the rodeo—but if you think about it objectively, it’s a ridiculous sentence. A month or two is plenty long. (Ask anyone who has done time.)

You know what would make me feel safe? A rehabilitation program that educated and provided jobs for guys like my burglar. Whether his term was too long or just right, those eight years came to an end—and he wound up back on the street, less employable and more corrupted than before. And don’t get me started about prison conditions.

A serious national discussion about out-of-control prosecutors and crazy long sentences is long overdue. I hope Aaron Swartz’s death marks a turning point.

(Ted Rall is the author of “The Book of Obama: How We Went From Hope and Change to the Age of Revolt.” His website is tedrall.com.)

COPYRIGHT 2013 TED RALL

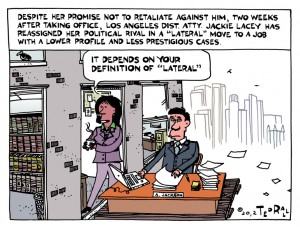

LOS ANGELES TIMES CARTOON: A Lateral Move

I draw cartoons for The Los Angeles Times about issues related to California and the Southland (metro Los Angeles).

This week: Two weeks after taking office, Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey has reassigned a political rival she beat in the November election from a prestigious high-profile job to a post where he will no longer try cases — a move he contends is a backward step for his career.