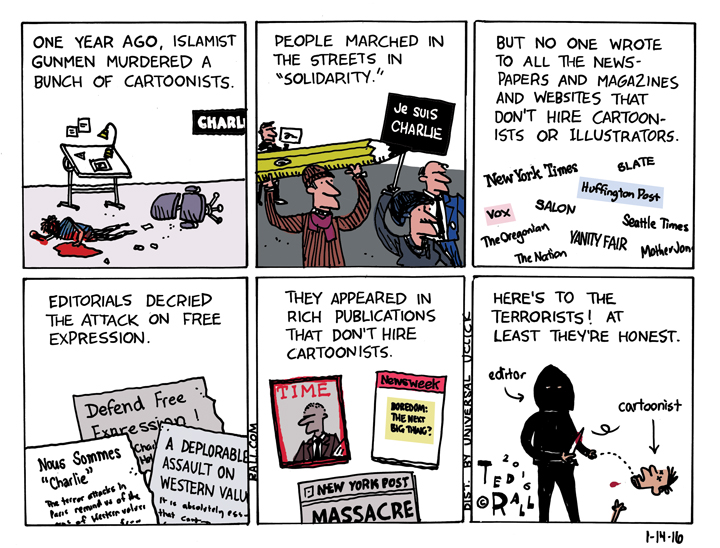

Syndicated Editorial Cartoonists Ted Rall, (from the left) and Scott Stantis (from the right) unpack the many layers from the week’s top stories.

First up, the Hunter Biden plea deal. The judge said it was unconstitutional and the defense wanted it to provide a blanket get-out-of-jail card. Why it fell apart and how it reflects the media’s disdain for anything that may conflict with its prevailing narrative. Ted and Scott take a rhetorical side trip to explore other issues they have been way in front of, and examine why the mainstream media takes so long to catch up to common sense.

Next up, the Federal Reserve Board continues to raise interest rates although it seems from this healthy economy that they shouldn’t. Scott argues against government overreach while Ted makes the case for deeper regulation of the American economy.

Lastly, Kevin Spacey, one of the best actors of his generation, has been found not guilty of sexual malfeasance in yet another trial. Ted and Scott discuss whether he should be welcomed back to the entertainment business.

Watch the Video Version of the DMZ America Podcast: