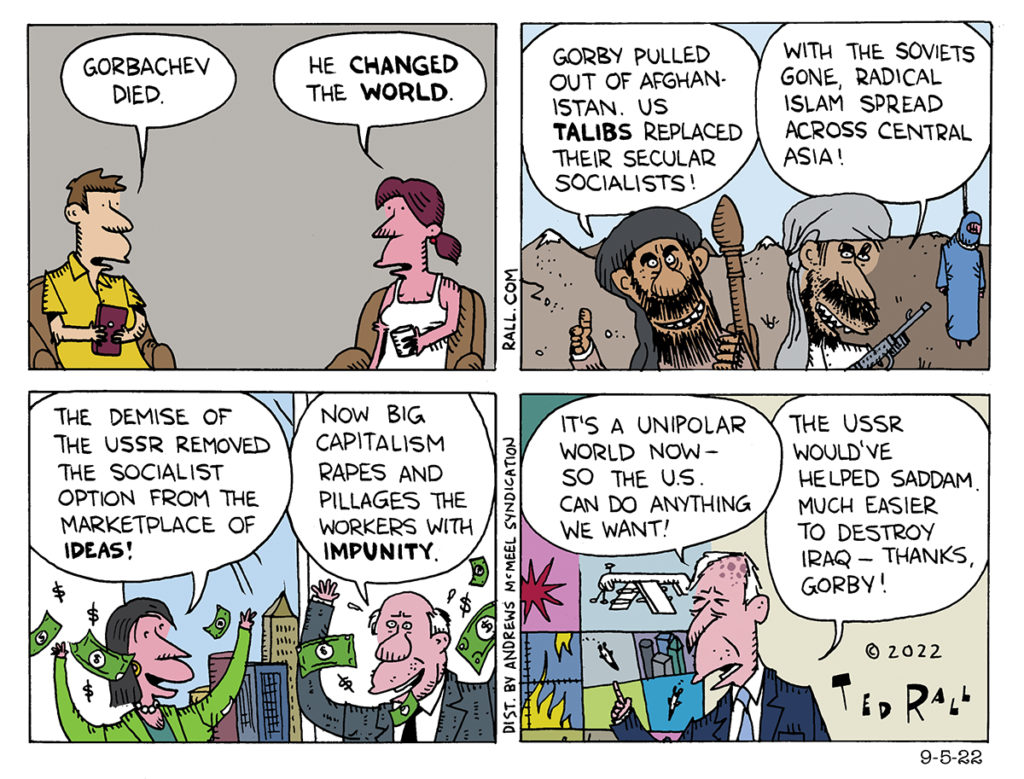

Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev died, leaving a legacy of ruin that is often overlooked by triumphalist American analysts who still gloat over our so-called victory in the Cold War.

4 Lessons from Afghanistan

One year ago, America lost yet another war. Afghanistan is right back where it was two decades ago, under control of the Taliban. The question is: what, if anything, have we learned?

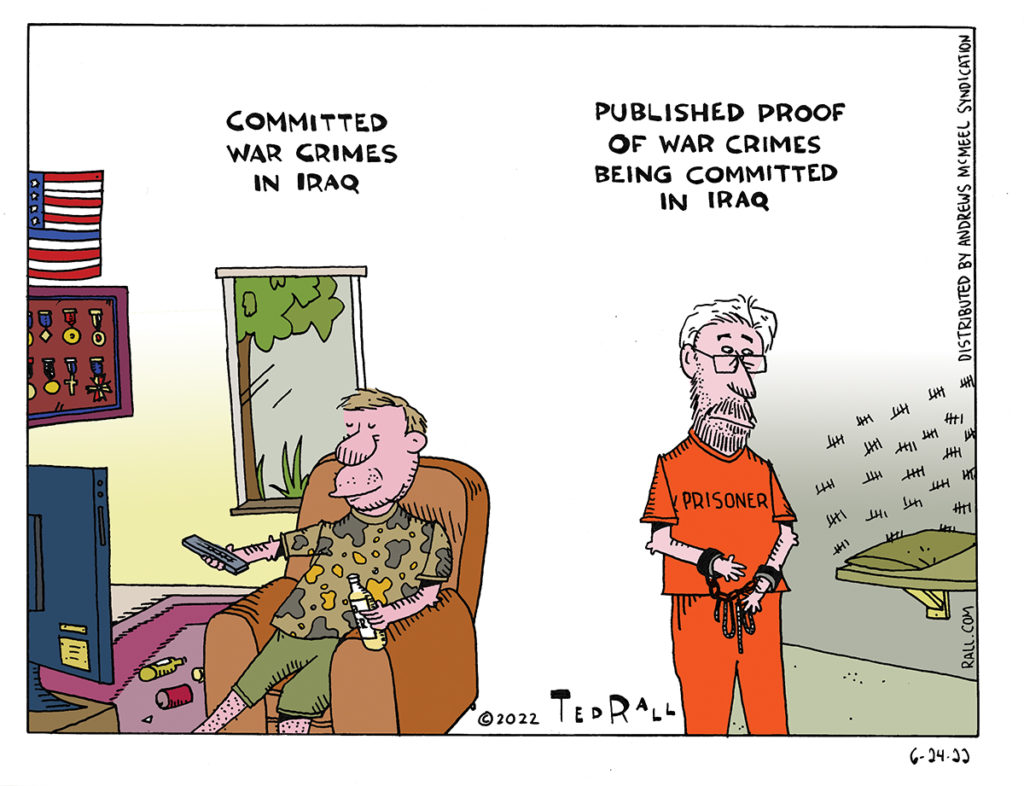

Make any mistake you like, but don’t make the same mistake twice—or four times. The U.S. committed the same errors of omission and commission in Vietnam, and then Iraq; our failure to draw intelligent conclusions from those conflicts and apply them going forward led us to squander thousands of more lives and billions of more dollars in Afghanistan. Here we go again: unless we learn from our decision to go to war against Afghanistan and then occupy it, we are doomed to our next debacle.

Afghanistan Lesson #1: When politicians tell you that war is necessary and justified, always be skeptical.

President George W. Bush told us that we had to invade Afghanistan in order to bring Osama bin Laden to justice for 9/11. Almost certainly false; the guy was probably in Pakistan. And if bin Laden was in Afghanistan, Bush could have instead accepted the Taliban’s repeated offers to extradite the accused terrorist. Bush argued the war was necessary to take out four training camps allegedly used by Al Qaeda. But Bill Clinton bombed six such camps using cruise missiles in 1998, no war required.

Bush’s casus belli for Afghanistan made no more sense than his evidence-free weapons of mass destruction in Iraq or the fictional Tonkin Gulf incident LBJ used to get us into Vietnam. It’s long overdue for American voters to download and install a sturdy BS detector about wars, particularly those on the other side of the planet.

Lesson #2: Never install a puppet government.

Of the countless mistakes the U.S. made in Vietnam, no single screwup led to more contempt for the United States than its sustained support for the deeply unpopular, brutal, autocratic president of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem. Saddam Hussein looked positively brilliant in comparison to the exiled con man, Ahmed Chalabi, whom Bush tried to replace him with. Rather than allow Afghans at the post-invasion loya jirga council meeting to choose their own ruler, like the long-exiled king, the U.S. pulled strings behind the scenes by buying the votes of corrupt warlords in support of the dapper Hamid Karzai, who had little popular support. Three years later, even the establishment New Yorker conceded that “if American troops weren’t there, Karzai almost certainly wouldn’t be, either.”

The U.S. propped up Karzai and his successor and close ally Ashraf Ghani for 17 more years.

Lesson #3: Never try to exclude an entire political party or group from a nation’s political life.

The Taliban’s base of power was the ethnic Pashtuns who comprised 40% of Afghanistan’s population. Yet the Taliban were not permitted to attend the loya jirga. They could not run in parliamentary elections under the U.S.-backed puppet government. Marginalized and “alienated from the central government, which they believe[d was] unfairly influenced by non-Pashtun leaders and interests,” in the words of a prescient 2009 Carnegie Endowment white paper, they had two options: stand down and shut up, or resort to guerilla warfare.

The U.S. messed up the same way in Vietnam and Iraq. In U.S.-backed South Vietnam, communists and their nationalist allies were excluded from electoral politics. Iraq’s Sunnis, 32% of the nation, lost their leader when Saddam was overthrown by U.S. forces, got fired from the military and other jobs by Bush’s idiotic deBaathification policy and humiliated by America’s new darlings, Shia politicians and their factions—sparking a bloody civil war and leading to U.S. defeat.

Lesson #4: Never be a sore loser.

European powers that offered financial assistance and training to their former colonies after independence in places like Africa continued to enjoy influence within those countries. Examples include the UK’s relationship with India and France’s role in Mali, Senegal, the Central African Republic and even Algeria, which cast off the French yoke after an eight-year-long struggle famously characterized by torture and terrorism.

The United States should try something similar when it loses its wars of aggression: lick its wounds, acknowledge its mistakes and offer to help clean up the messes it makes when it withdraws from a country strewn with mines and cluster bombs.

It took 20 years before the U.S. reengaged with Vietnam after the fall of Saigon—two decades of squandered rapprochement and lost international trade. This occurred despite the precedent of World War II, in which U.S. occupation authorities worked to insinuate themselves with their defeated enemies Germany and Japan almost on day one, two relationships that paid off for all concerned.

Its nose bloodied by its debacle in Iraq, the U.S. has allowed Iran to become the dominant outside power inside the country.

And now the U.S. is doing the same thing in Afghanistan as in Iraq—nothing. Afghans are gaunt and hungry because of drought and the U.S. decision to cut off aid and frozen Afghan government funds. The economy is collapsing. The enormous U.S. embassy in Kabul is closed, making it impossible for Afghans to contact the U.S. government.

All that investment of money and time, and who will get the more than $1 trillion in untapped natural resources, including copper, lithium, and rare-earth elements? China, most likely. If the U.S. could get over itself, it might salvage some influence over the new Taliban government in Kabul and open new markets. Let girls go to school and women work, President Biden could tell them, and we’ll release some funds. Arrest and hand over figures like the recently droned Ayman al-Zawahiri, who was living in Kabul, and we’ll restore aid. Carry out more reforms and we’ll establish diplomatic ties.

Picking up your toys and going back to your house after losing a fight might feel good. But it’s immature and counterproductive in a world in which success depends on having friends and collaborators.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

In Actual Russia, No Sign of Sanctions

It’s time to get real. It’s been time to get real. Russia has won its war against Ukraine.

This outcome comes as no surprise. Anyone with access to a map could see that the chances of Ukraine prevailing against Russia were slim to none.

The only way Ukraine could have emerged victorious—which would, according to the Ukrainians themselves, mean pushing it out of Crimea and deposing the separatist pro-Russian republics of Donetsk and Luhansk—would have been if the United States and its Western allies had been willing to launch nuclear weapons, which would have led to global annihilation. Once the decision was made not to start World War III, Ukraine’s defeat became inevitable. This, everyone sane knows, is for the best.

Determinative to this conclusion was an unusual pair of motivations. Normally, when a war is fought on one country’s territory, the invaded country fights harder than the invading forces. Paradoxically, despite suffering damaged infrastructure, the invaded state enjoys the homefield advantages of complete knowledge of the battlefield and much shorter supply lines. Aside from sporadic cross-border missile strikes, this war has been fought entirely on Ukrainian territory.

This conflict is different because Russia has to win; it cannot walk away. Ukraine has a 1,200-mile border with Russia, it wants to join an anti-Russia military alliance and its government was openly hostile to Russia before the war. And when Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, its armies came through Ukraine, where the Nazis were greeted as liberators. Unlike America, which could bring its troops home after losing on the other side of the world in Afghanistan and Iraq and shrug off its imperialist misadventures and could leave Vietnam after pretending that more political will on the home front would have resulted in victory, Russia sees its military operation as existential. Ukraine isn’t a misbegotten side project. It’s as essential in the same way the United States would respond to a Canada that turned hostile to the U.S.

Unfortunately and dangerously, American media consumers are being pounded with an endless deluge of propaganda promoting the ludicrous idea that Ukraine is winning and/or will ultimately prevail militarily. This fantastical assertion props up political support for shipping $60 billion worth of weapons to Ukraine, with more on the way—never mind the 70% that Zelensky’s wildly corrupt government sells on the black market and the Javelin missile systems that wind up for sale on the dark web. (Christmas is coming! Don’t forget your favorite political cartoonist and columnist.) By way of comparison, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that we could abolish homelessness here for $20 billion.

We’re also being told that Russia is crumbling under the crushing blow of vicious Western sanctions deployed as part of the White House’s openly-stated war aim that it wants “to see Russia weakened.” The Russian economy, it is said, is collapsing. Russian elites, they say, will soon overthrow President Vladimir Putin.

Let me tell you firsthand: there is zero sign of economic distress in Russia.

I’ve spent the last two weeks in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Russia’s two biggest cities. Stores are bustling, people are spending, unemployment is low and still falling, there are lines at ATMs and whatever else is happening, the economy is anything but bad. The Galeria Mall across the busy street from my hotel in Saint Petersburg has a few closed stores shut down by Western chains but the majority remain and consumers are shopping like mad. European and American tourists are few and far between, but it’s exactly the same here in sanctions-free Istanbul where I’m writing this. Westerners stopped coming at the start of the COVID-19 lockdown two years ago and still haven’t returned. If Russians are unhappy with Putin—and they’re not—it’s not because of the economy.

I know from bad economies; where I live in New York, crime is out of control, homeless people go untreated for an array of mental illnesses and some are killing people, and being killed, and many storefronts have been empty and boarded up since the beginning of the pandemic. Any New Yorker would or should happily trade places with their Muscovite counterpart, who lives in a city with clean streets and subways that don’t serve as rolling homeless shelters and where life feels as if COVID-19 was never a thing. News stories that claim Russia is on the ropes are a giant magnificent pile of lies so over-the-top that I can’t help but be impressed by their glorious audacity and easily-debunked mendacity. All you have to do is go to Russia, as I did, and see for yourself that it’s all bull—but hey, that’s a lot of trouble—because of sanctions that seem to be hurting us more than them.

Self-delusion is more fun. Who, after all, should you trust? The same U.S. state media that told you Saddam had WMDs? Or some cartoonist-columnist who told you, well in advance, that the U.S. didn’t stand a chance in Afghanistan, Trump would win in 2016 and that he would attempt a coup d’état to remain in power?

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

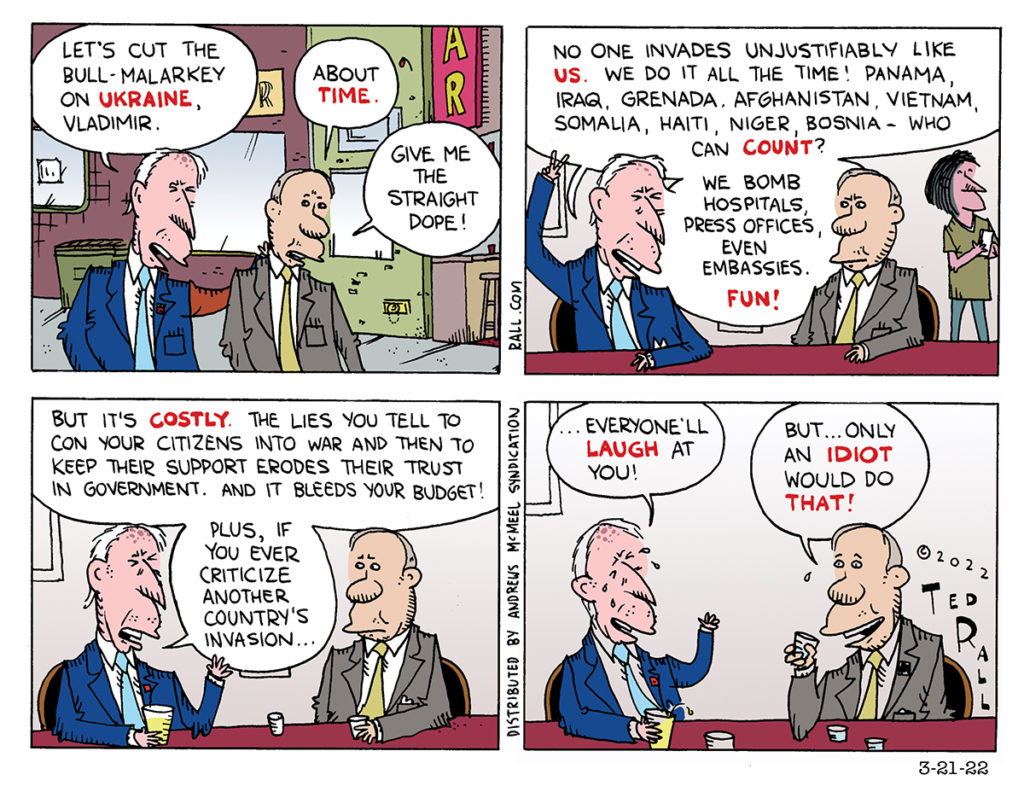

Finally, Straight Talk on Ukraine

What if Joe Biden were to admit to Vladimir Putin the obvious truth, that the United States is an expert in all the acts of villainy Russia is committing and accused of in Ukraine? What if he warned Russia that it would suffer the same loss of credibility United States has in criticizing Russia?

Perhaps We Need More Uncertainty, Maybe

“We know where they are,” Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said in March 2003 about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. “They’re in the area around Tikrit and Baghdad and east, west, south and north somewhat.” We found nothing. Rumsfeld knew nothing. A year after the invasion, most voters believed the Bush Administration had lied America into war.

At the core of that lie: certainty.

The 2002 run-up to war was marked by statements that characterized intelligence assessments as a slam dunk. “Simply stated, there is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction. There is no doubt he is amassing them to use against our friends, against our allies, and against us,” Vice President Dick Cheney said in August 2002. “These are not assertions. What we’re giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence,” Secretary of State Colin Powell told the UN.

Rumsfeld knew that if he said that Saddam probably had WMDs it wouldn’t have been enough. Americans required absolute certainty.

Imagine if the Bushies had deployed an honest sales pitch: “Though it is impossible to know for sure, we believe there’s a significant chance that Hussein illegally possesses weapons of mass destruction. Given the downside security risk and the indisputable fact that he is a vicious despot, we want to send in ground troops in order to remove him from power.” The war would still have been wrong. But our subsequent failure to find WMDs wouldn’t have tarnished Bush’s presidency and America’s international reputation. Trust in government wouldn’t have been further eroded.

False certainty has continued to poison our politics.

Four months into Trump’s presidency 65% of Democratic voters didn’t believe he had won fairly or was legitimate. 71% of Republicans now say the same thing about Biden. What’s interesting is the declared certainty of Democrats who decry Trump Republicans’ “Big Lie.” Biden probably did win. But it’s hardly certain.

It is not popular to say so, but there is nothing unreasonable or insane or unpatriotic about questioning election results. From Samuel Tilden vs. Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876 to Bush vs. Gore in 2000 many Americans have had good reason to wonder whether the winner really won. Only an omniscient deity could know for certain whether all 161 million ballots were counted correctly at all 132,556 polling places in the 2020 election.

Democracy requires faith. If evidence indicates that our faith is unwarranted it must be fully investigated; otherwise we must assume that official results are accurate.

The Republicans’ refusal to accept the official results is only slightly less justifiable than the Democrats’ overheated “Big Lie” meme.

“We have been far too easy on those who embrace or even simply tolerate this idea [that Trump was the true winner of the 2020 election], perhaps because it has completely taken over the Republican Party, and we still approach any question on which Republicans and Democrats disagree as though it must be given an evenhanded, both-sides treatment,” Washington Post columnist Paul Waldman wrote January 6th. “We have to treat those who claim Trump won in precisely the same way we do those who say the Earth is flat or that Hitler had some good ideas. They are not only deluded, they are either participating in, or at the very least directly enabling, an assault on our system of government with terrifying implications for the future. They are the United States’ enemies. And they have to be treated that way.”

Whoa. I am terrified of the slippery-slope implication that even talking about a topic is out of bounds. If mistrust of the competence and integrity of thousands of boards of elections and secretaries of state and public and private voting machines makes one a domestic enemy of the United States, what does that say about the 65% of Democrats and 71% of Republicans who doubted the results of the last two elections?

Why not just say that we think Biden won and there’s no reason to believe otherwise? It may be easier to shout down doubters than to make a well-reasoned argument but our laziness betrays insecurity.

Every day we make decisions based on uncertainty. The plane will probably land safely. The restaurant food probably isn’t poisoned. The dollar will probably retain most of its value. Why can’t Democrats like Waldman admit that election results are inherently uncertain? Republicans know it—at least they know it when the president is a Democrat—and Democratic arguments to the contrary of what is obviously true only serve to increase polarization and mutual mistrust.

Vaccination and masking politics are made particularly venomous by rhetorical certainty that, given that science is constantly evolving and COVID keeps unleashing new surprises, cannot be intellectually justified. Those of us who have embraced masks and vaccines (like me) ought to adopt a humbler posture: I’m not an epidemiologist, I assume that scientists know what they are doing, I’m scared of getting sick so I’m following official guidance. Sometimes, as we know from history, official medical advice turns out to be mistaken. I’m making the best guess I can. Most of us are blindly feeling our way through this pandemic. We should say so.

We also need to express uncertainty about climate change. There is scientific consensus that the earth is warming rapidly, that human beings are responsible and that climate change represents an existential threat to humanity. I believe in the general principle. But it’s irresponsible and illogical to attribute specific incidents to climate change considering that extreme weather existed centuries before the industrial revolution. We will never reach climate change deniers by overreaching as when the Post described late December’s Colorado wildfires as “fueled by an extreme set of atmospheric conditions, intensified by climate change, and fanned by a violent windstorm.” Why not instead say “probably intensified” or “believed to have been intensified”?

Those of us who believe greenhouse gases are warming the planet should argue that, while nothing is ever 100% certain, it’s a high probability and, anyway, what’s wrong with reducing pollution? People who are certain that climate change isn’t real may be annoying, and given that the human race is at stake, perhaps dangerous. But the answer to incorrect certainty isn’t equal-and-opposite correct certainty.

It’s uncertainty.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the weekly DMZ America podcast with conservative fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

Who Lost Afghanistan? H.R.

Congress, the media and many voters are asking military officials this week: how did we lose the Afghan war? I’ve been reading a book, “The Afghanistan Papers,” by Washington Post reporter Craig Whitlock, that shows how America messed up its longest war. (Every now and then, corporate media hypes something that’s actually worth reading.)

What it does not show, and what Pentagon leaders don’t seem to understand, is why.

Whitlock’s book reads like a synopsis of the many essays, books and cartoons I produced over 20 years, which were rejected by most newspapers and news websites because editors and producers refused to publish content that criticized the war.

For instance, Whitlock echoes my longstanding insistence that the Taliban posed no threat to the United States: “The Bush administration made another basic mistake by blurring the lines between Al Qaeda and the Taliban,” he writes. “The two groups shared an extremist religious ideology and a mutual support pact, but pursued different goals and objectives. Al Qaeda was primarily a network of Arabs, not Afghans, with a global presence and outlook… In contrast, the Taliban’s preoccupations were entirely local… The Taliban protected bin Laden and built a strong alliance with Al Qaeda but Afghans did not play a role in the 9/11 hijackings and there is no evidence they had advance knowledge of the attacks.”

We spent 20 years fighting people who meant us no harm and couldn’t have hurt us even if they had wanted to.

While the after-action investigation is necessary and interesting — I’m following it every day — the postmortem necessarily focuses on acts of commission and omission during the war, after it started. Perhaps because both major political parties were equally complicit in the invasion as a knee-jerk response to 9/11, or because both the Democrats and the Republicans are in the pockets of the defense industry, no one is questioning the decision to start the war, only its atrocious execution and embarrassing wind-down.

The sad truth is, the same screwups will continue. We will keep beginning wars against countries we ought to stay away from. We will make the same mistakes throughout the duration of those wars. Nothing will change because nothing has changed.

The reason is simple: personnel. Presidents keep hiring the wrong people to make decisions about war and peace. And the right ones never have a seat at the table in the room where it happens.

Voters who want to avoid fighting another Afghanistan war must insist upon candidates who promise to include anti-interventionists among their top military advisers and in their cabinet. They should withhold their votes from politicians, even liberal Democrats, who refuse to promise to include pacifists, war skeptics and isolationists among their inner circle. Personnel is policy, they say in Washington, and that is never truer than when someone near the President of the United States suggests military action.

Eisenhower was one of the last American political leaders to understand the importance of drawing advice from an ideologically diverse group. “I know of only one way in which you can be sure you’ve done your best to make a wise decision,” Ike said. “This is to get all of the people who have partial and definable responsibility in this particular field, whatever it may be. Get them with their different viewpoints in front of you, and listen to them debate.”

Unfortunately, there’s hardly any debate on whether or not to go to war.

What passed for diversity of opinion in the George W. Bush cabinet was a group of hawks with different styles and proclivities, but hawks nonetheless. After 9/11 Bush’s “war cabinet” included his notoriously bellicose Vice President Dick Cheney, National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, Secretary of State and former General Colin Powell, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Chief of Staff Andrew Card, and CIA director George Tenet. No experts on Afghanistan were invited. No academics, no journalists, no one who had even spent a single night in a house in Afghanistan.

Predictably, all the choices discussed involved military action. “The war cabinet considered several options for the U.S. pursuit of Al Qaeda in Afghanistan: a strike with cruise missiles, cruise missiles combined with bomber attacks, or ‘boots on the ground,’ that is U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan,” James P. Pfiffner noted in the journal Issues in Governance Studies. Most Americans now agree that the war was a mistake.

Bush should have stayed out of Afghanistan entirely.

Some people felt that way at the time, when it mattered, before we wasted trillions of dollars and killed hundreds of thousands of innocent people. But antiwar Americans were ridiculed when they weren’t simply being ignored. Bush couldn’t make the right decision because no one who had his ear ever argued for it.

Joe Biden is a different and hopefully better president than George W. Bush, yet his group of advisers suffers from the same lack of ideological diversity. No one who generally opposes war meets with the president on a regular basis. When there’s a foreign policy crisis, none of Biden’s senior advisers can be counted upon to argue against getting involved.

Understanding how we lost Afghanistan is useful.

If we want to understand why we lost Afghanistan, and if we want to stop the next Afghan war before it starts, we should look at who.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of a new graphic novel about a journalist gone bad, “The Stringer.” Order one today. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

Democrats Share the Blame for Afghanistan

Joe Biden is taking heat from Democrats, not for his decision to withdraw from Afghanistan—that’s popular—but for his haphazard pullout that, self-serving Rumsfeldian stuff happens, wars end messily platitudes aside, could have been executed more efficiently. They blame George W. Bush for starting America’s longest war, arguing that what he began inexorably led to our most shocking military defeat and its humiliating aftermath.

I am sympathetic to any and all criticism of our intervention in Afghanistan. I was an early critic of the war and got beaten up for my stance by media allies of the Bush administration. But the very same liberals who now pretend they’re against the Afghan disaster stood by when it mattered and did nothing to defend war critics because Democrats—political leaders and voters alike—went far beyond tacit consent. They were actively complicit with the Republicans’ war, at the time of the invasion and throughout the decades-long occupation of Afghanistan.

Now the deadbeat dads of defeat are trying to stick the GOP with sole paternity. This is a ridiculous attempt to rewrite history, one that damages Democratic credibility among the party’s progressive base, which includes many antiwar voters, and risks the possibility that they will make the same mistake again in the future.

Twenty years later, it is difficult for some to believe that the United States responded to 9/11 by cultivating closer ties to the two countries with the greatest responsibility for the attacks, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, and attacking a country that had nothing to do with it, Iraq and another one that had tenuous links, Afghanistan. Yet that’s what happened. And Democrats participated enthusiastically in the insanity.

The sweeping congressional authorization to use military force against Afghanistan and any other target chosen by the president (!) was introduced in the Senate three days after the attacks by Tom Daschle, the then-Democratic majority leader. Every Democratic senator supported destroying Afghanistan. So did every Democratic member of the House of Representatives except for one, Barbara Lee, who was roundly ridiculed as weak and naïve, received death threats and was denied leadership posts by her own party to punish her for refusing to play ball. The legal justification to attack the Taliban was a bipartisan affair.

Democratic support for Bush’s war reflected popular sentiment: voters of both parties signed off on the Afghan war by wide margins. Even after weeks of bombing that featured numerous news stories about innocent Afghan civilians being killed willy-nilly, 88% of voters told Gallup that they still approved of the military action. Approval for the war peaked at 93% in 2002 and started to decline. Nevertheless, popular support still hovered around 70% throughout the 2008 presidential campaign, a number that included so many Democrats that then-Senator Barack Obama ran much of his successful primary and general election campaign on his now-obviously-moronic message that we “we took our eye off the ball in Afghanistan” when Bush invaded Iraq. “Our real focus,” Obama continued to say after winning the presidency, “has to be on Afghanistan.”

Nine months into his first term, Obama felt so confident that Democratic voters supported the war that he ordered his surge of tens of thousands of additional soldiers above the highest troop level in Afghanistan under the Bush administration. 55% of Democrats approved of the surge. Domestic support for the war only went underwater after the 2010 assassination of Osama bin Laden by U.S. troops in Pakistan seemed to render the project moot.

There was a strong antiwar movement based on the left throughout the Bush and Obama years—against the invasion and occupation of Iraq. Hundreds of thousands of protesters marched against the Iraq war. Opposition was sustained over the years. Far fewer people turned out for far fewer protests against the Afghanistan war. It’s impossible to avoid the obvious conclusion: even on the left, people were angry about Iraq but OK with Afghanistan.

There is nothing wrong with criticizing the Republican Party and President George W. Bush for the decision to invade Afghanistan. The war was their idea. But they never could have started their disaster, much less extended and expanded it under Obama, without full-throated support from their Democratic partners and successors.

This story has few heroes.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of a new graphic novel about a journalist gone bad, “The Stringer.” Order one today. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

20 Years After 9/11, We’re Still Morons

If crisis creates opportunity, we couldn’t possibly have squandered the possibilities presented by 9/11 more spectacularly. We certainly couldn’t have failed its tests more completely. Twenty years after 9/11, it is clear that the United States is ruled by idiots and that we, the people, are complicit with their moronic behavior.

We had to do something. That was and remains the generic explanation for what we did in response to 9/11—invading Afghanistan and Iraq, directing the CIA to covertly overthrow the governments of Haiti, Venezuela, Belarus, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and a bunch of other countries, lamely legalizing torture, kidnapping via extraordinary rendition to Guantánamo and other concentration camps, building a drone armada and sparking a drone arms race.

Acting purely on speculation, news media was reporting as early as the afternoon of September 11 that Al Qaeda was responsible. That same day, Vice President Dick Cheney argued for invading Iraq. We began bombing Afghanistan October 7, less than a month later, without evidence that Afghanistan was guilty. A week later, the Taliban offered to turn over bin Laden; Bush refused. Before you act, you think. We didn’t.

What should we have done—after giving it a good think?

A smart people led by a good president would have had three priorities: bring the perpetrators to justice, punish any nation-states that were involved, and reduce the chances of future terrorist attacks.

The 19 hijackers were suicides, but plotters like Al Qaeda’s Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who lived in Pakistan, were not. Since we have an extradition treaty with Pakistan, we could have asked Pakistani authorities to arrest him and send him to face trial in the U.S. or at the international war crimes tribunal at The Hague. Instead, we kidnapped him to CIA “dark sites” including Gitmo and subjected him to waterboarding 266 times. Because of this and other torture, as well as his illegal detention in violation of habeas corpus, KSM can’t face trial in a real, i.e. civilian, court. Not only will 9/11 families never see justice carried out, we’ve managed to turn KSM into a victim, just as he wanted.

The Inter-Services Intelligence agency, Pakistan’s CIA, financed and provided intelligence to Al Qaeda. Pakistan harbored bin Laden. Pakistan played host to hundreds of Al Qaeda training camps. Pakistanis I talked to after 9/11 were shocked that the U.S. didn’t attack their country, instead giving its Taliban-aligned dictator General Pervez Musharraf billions in military and financial aid.

Evidence linking top Saudi Arabian officials to 9/11 has been scarce. But 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudi, several are reported to have met with mid-level Saudi intelligence agents before the attacks, and, most notably, Saudi Arabia exports its radical brand of Sunni Islam, Wahhabism, all over the world. The Taliban and Al Qaeda initially recruited many of their members from Wahhabi madrassas financed by the Saudis in Pakistan and Central Asia.

We should have treated 9/11 for what it was: a crime. Policemen, not soldiers, should have tracked down the perps. They should have been given lawyers, not torture. They should have faced fair trials. But if we had to go the military route, we should have invaded Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, the two countries responsible, not Afghanistan and Iraq, two countries that had nothing to do with it. Pakistan and Saudi Arabia were and remain far more dangerous to their neighbors than Afghanistan or Iraq.

Occupying Saudi Arabia, the world’s biggest exporter of Islamic extremism and global terrorism, would have done a lot to reduce the threat of another 9/11. But the most effective way to make us less of a target is to make the rest of the world look upon us with favor. Some people will always hate us. That’s inevitable. Our goal should be to reduce their number to as close to zero as humanly possible.

We can’t eliminate anti-Americanism by killing its adherents. We’ve been trying to do that for 20 years using drones and missile strikes; all we’ve accomplished is killing a lot of innocent people and making the rest of the world look at us with disgust and contempt. You kill anti-Americanism by treating people everywhere with respect and kindness. That includes those we suspect of doing us harm.

Unfortunately for us and the world, we learned nothing from 9/11. Not even losing Afghanistan back to the Taliban in the most humiliating U.S. defeat since Vietnam, having nothing to show for 20 years of war, has taught us a thing. We’re still a hammer that sees everything as a nail, a blunt, stupid people whose idea of a plan is to keep indiscriminately bombing innocent civilians.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of a new graphic novel about a journalist gone bad, “The Stringer.” Order one today. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)