Who can blame the gravekeepers at Arlington? All the victims of our leaders’ lies look the same.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Holiday in the Sun

Travel Planning for Afghanistan

How are things going in Afghanistan? The best way to find out is to go see for yourself. I’m doing that this August.

You can tell a lot even before you go. I’m in the planning stages: reserving flights, applying for visas, buying equipment.

“Whatever you do,” a friend emailed me from Kabul, “don’t fly into the Kabul airport.” He wasn’t worried that my flight would get shot down by one of Reagan’s leftover Stinger missiles—although there’s a risk of that. (In order to improve the odds, pilots corkscrew in and out.)

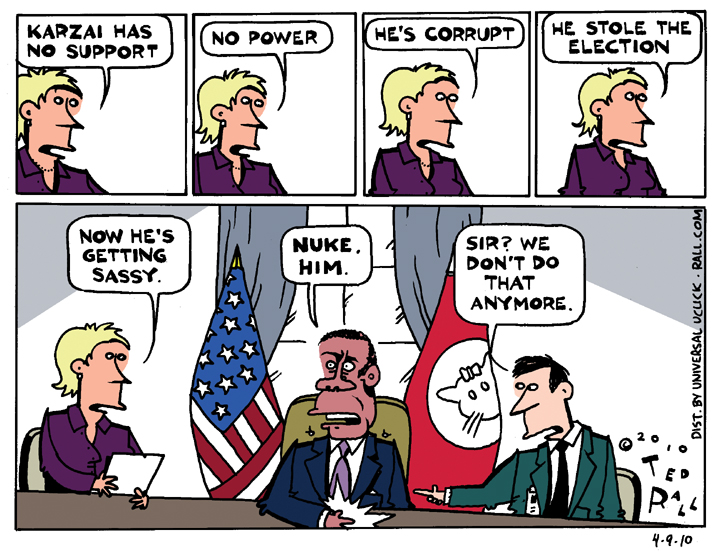

His concern is corrupt cops. “[Afghan president Hamid] Karzai’s policemen are crazy,” my normally taciturn buddy, who works for an NGO, elaborated. “They’ll hold you up at gunpoint right in the airport.”

One option is to hitch a flight on a military transport to the former Soviet airbase north of town at Bagram, now a U.S. torture facility being expanded by the Obama Administration in order to accommodate detainees being transferred from Guantánamo. But I’m an old-fashioned journalist. War reporters shouldn’t tag along with soldiers.

So I’m not flying into Kabul. Which works out, since getting to my destination—Taloqan, in Takhar province near the Tajik border—would have required traveling north toward Mazar-e-Sharif from Kabul. Among the highlights of the Kabul-Mazar road are landslides and a trek through the war-scarred Soviet-era Salong Tunnel. It also offers an assortment of thugs both political (Taliban) and apolitical (bandits).

To avoid corrupt airport cops and the dicey north-south highway, I’ll fly into Dushanbe, the capital of Afghanistan’s northern neighbor, Tajikistan. This means spending an extra $800 on airfare, not to mention chancing travel on one of Tajikistan Airlines’ aging Tupolev 154s. It takes a full day to drive from Dushanbe to the Afghan border on mostly unpaved roads.

But I’ll be stuck in Dushanbe for two or three days waiting for government permits. You can’t travel to the special “security zone” along the border with Afghanistan without a permission document issued by the Tajik Ministry of Foreign Affairs. When I met the minister in 2001, I asked him whether treating the 100-kilometer zone like no-man’s land sent an unfriendly message to the Afghans. He laughed. “Afghanistan,” he said, “is our very difficult neighbor. If they behave better, so will we.” The policy remains in place.

No journalist operating in a war zone is safe without a fixer. Things you can easily do yourself back home can be impossible in the Fourth World. A fixer makes things happen: government permits, cars and drivers, places to stay. I’ve accumulated a set of fixers throughout Central and South Asia over the years.

But it’s hard to arrange a fixer in advance in Afghanistan. There’s hardly any mail, telephone service or electricity outside Kabul, much less email. I’ll probably have to just show up, then hire people as I travel.

Nevertheless, I contacted another Kabul-based Friend of Rall about lining up fixers for the regions I plan to visit: Takhar, which I mentioned above, Kunduz, then northern Afghanistan en route to and around Heart (near the Turkmen and Iranian borders), and finally Nimruz province.

There’s heavy fighting in Kunduz. The Taliban recently beheaded four guards working for U.S. forces near Herat. In Zaranj, the provincial capital of Nimruz, suicide bombers just took out the governor’s compound.

“No one wants to go where you’re going,” my friend informed me.

The average salary in Afghanistan is $30 per month.

“I pay $150 a day,” I replied.

“I know a guy. But he’s a whiner. He’ll complain about it the whole time. And you’ll have to promise a death bonus to his wife if something happens.”

Communications are a challenge. I want to file a daily cartoon blog. I can scan a drawn cartoon into my laptop, assuming it doesn’t get stolen by some greedy border guard. But how will I access the Internet?

I can rent a satellite phone and use dial-up. It won’t be fast; at 9600 bps it takes an hour to send one a simple black and white cartoon. And it won’t be easy. Dial-up lines drop. In 2001, when I paid $7 a minute for satellite service, I cried when that happened. The search for power will be endless. Solar panels, car batteries, renting a generator for an hour, whatever it takes to feed greedy phones and laptops.

I’m not complaining. I’m just saying.

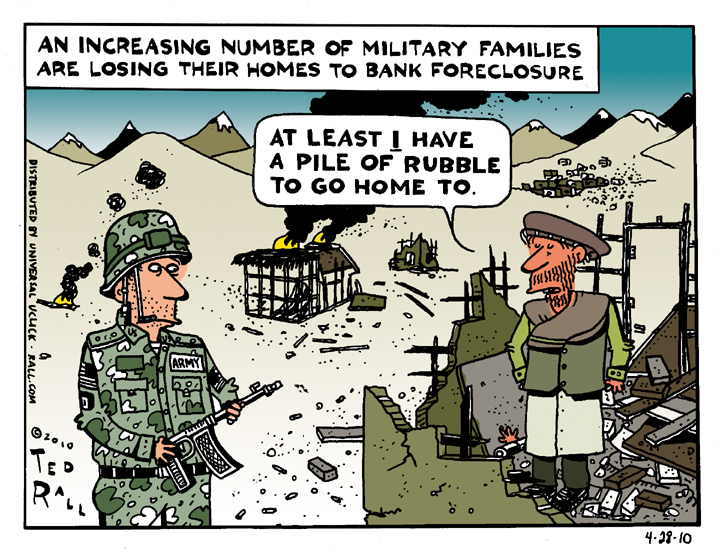

Afghans are allowed to complain. They live there.

Of course, the biggest inconvenience is danger.

Everyone worries about me. “Keep your head down.” “Come back alive.” “Don’t get killed.”

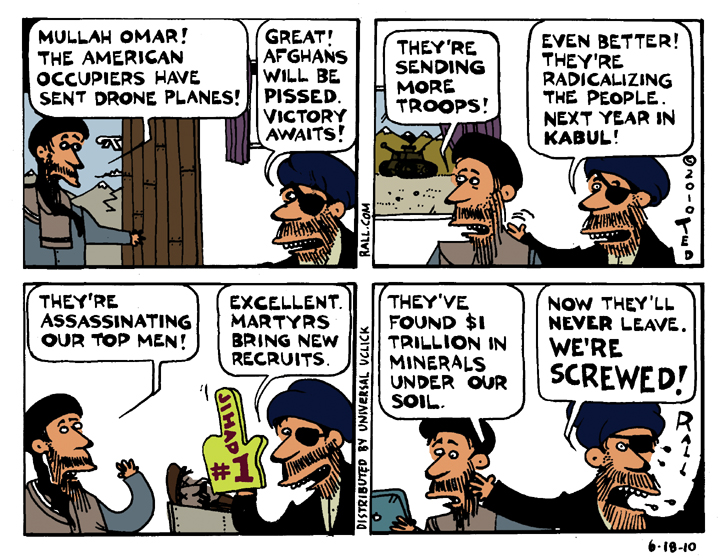

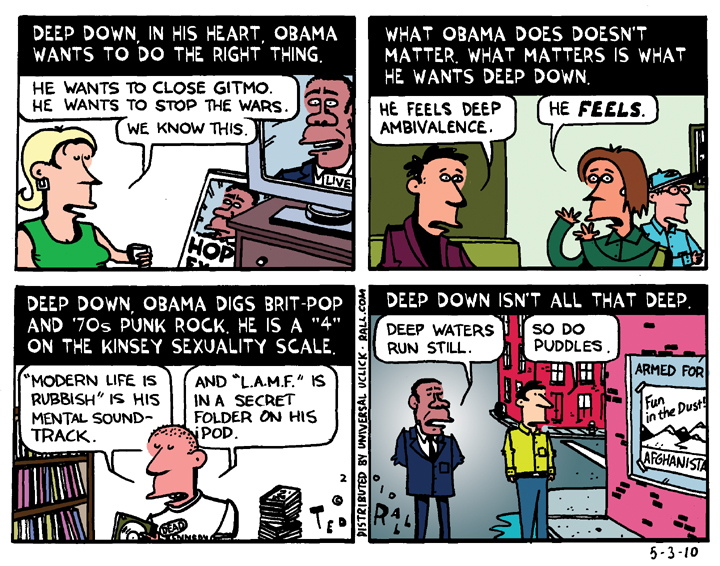

They’re sweet and loving sentiments. But they’re also kind of funny. Most of my friends still think of Afghanistan as the Good War, the one that had something—they’re not sure what—to do with 9/11. They think we’re there to help the Afghans. They think the carnage is in Iraq; actually, it’s more dangerous for U.S. troops in Afghanistan.

If the Afghanistan War is going so well, why is everyone so worried?

(Ted Rall is working on a radical political manifesto for publication this fall. His website is tedrall.com.)

COPYRIGHT 2010 TED RALL