Matt Bors has practically patented editorial cartoon criticism in his blog, but sometimes a cartoon is so turdy that I have to weigh in. When I heard the news this morning about the huge earthquakes and tsunamis in Japan, I knew that my colleagues could be counted upon to unleash a, er, tsunami of hackneyed clichés that would make readers eyes burn. It’s early yet, but I have not been disappointed.

First I offer this gem by David Fitzpatrick of the Tucson Daily Star:

When you live in Tucson, I guess everything looks like a cactus. Which explains Godzilla’s back plates. I love the collection of clichéed Japanese stuff, especially the temples and traditional city gates. Because, you know, Japan is so old-school and traditional and doesn’t have normal high buildings and stuff. But wasn’t Godzilla kind of a dick to Tokyo, what with shooting flames at it and stuff? This cartoon puts the “dick” in “ridiculous.”

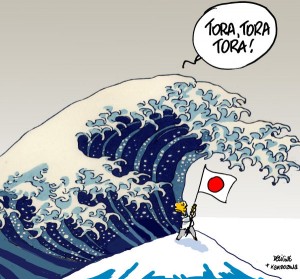

But leave it to France to jump the shark over the shark over the shark:

For those who didn’t see the 1970 film, “Tora! Tora! Tora!” was the signal that initiated the attack on Pearl Harbor. In other words, tectonics are getting even for one sneak attack with another. Geology is on America’s side and revenge is a bitch–even if it’s a long time coming. (Hiroshima and Nagasaki didn’t count.)