Americans are dumb.

That’s what people say. Especially foreigner non-American people.

But lots of Americans think that Americans are stupid. Not them, of course. They think other Americans are stupid.

It will not, even if you’re an idiot, come as a shock when I admit here that one of the Americans who think Americans are intellectually challenged is me.

Moronitude exists everywhere, of course. What makes stupidity in America stand out is that most Americans — the dumb ones — don’t think it’s bad to be dumb. Far from being ashamed, they’re dumb and proud. To the contrary — the dumb ones make fun of the small-and-constantly-shrinking population of intelligent ones: the “nerds.”

Want to study astrophysics? You’re a geek. No prom date for you!

I haven’t been everywhere, but I’ve traveled a lot, and what historians have documented as the tradition of anti-intellectualism in America seems to be pretty unique. Even Australia, land of our cultural Anglo-Saxon brethren, where dwarf-tossing was a thing (and for all I know may still be), never had an actual political party called the Know Nothings. We did, and not only that, but when historians reference the Know Nothings, no one ever chortles in derision. They nod knowingly. Maybe.

Flat affect. That’s what we do.

From “The Simpsons” to Green Day’s punk rock opera “American Idiot” to the semi-banned Mike Judge movie “Idiocracy,” our cultural commentators have taken repeated stabs at our “dumb and proud” national attitude. Yet it doesn’t change.

This, after all, is a country in which smart people have to pretend, in the words of an old ’80s song by Flipper, to “act stupider than you really are” in order to fit in.

Reality TV and televangelists aside, nothing epitomizes the national cult of stultification more clearly than our electoral politics. On the Republican side, well-read men and women of considerable accomplishment and with impressive educational credentials that belie what I am about to describe find themselves pretending to believe in things they and everyone else with half a brain can’t possibly believe to be true — because so of the voters they need are just that damned stupid. This is how we get Ted Cruz, no dummy he, pretending not to believe that climate change is caused by humans. Not to mention a bunch of governors and senators — senators! — claiming to think the earth is about 6,000 years old because: Bible. And to believe in “God.”

Just last week, a friend who hung out with George W. Bush told me something I’ve heard often enough before to believe: the guy is actually smart.

In a way, this comes as a relief, because: launch codes. Also Yale and Harvard. Even a legacy admit shouldn’t be half as much of the colossal idiot brush-clearing hick Bush pretended to be his entire political life.

There were hints of Bush’s non-stupidity. Every now and then, his aw-shucks cornpone veneer would flake off, the Connecticut Yankee inflection of a grandson of Prescott Bush peeking out like the cobblestones and streetcar tracks of an old paved-over road after a hard winter. That stupid accent — all fake!

Which reminded me of something Bush biographer Kitty Kelly reported: after losing a local election in Texas, Dubya swore, Scarlet-like, to never get out-countrified again. And he didn’t. And it worked.

How depressing.

Given how much I beat up Generalissimo El Busho while he was bombing and Gitmo-ing and bank-bailing, it’s only fair that I point out: he’s one of many. Obama and Hillary both apply a reverse-classist downscaling filter to their locutions, and Jesus H. W. Christ, it’s so over-the-top phony, am I the only one who can tell?

Speaking of which, I attribute all of the Bernie Sanders-Donald Trump surge to the two outsiders’ surprisingly unscripted authenticity, part of which derives from their unspun, startling, old-school New York accents. Platform planks have taken a back seat to reality. Which says something.

Not that the two mavericks of right and left aren’t forced to breathe the sludgy water of stupidism through their previously pure gills.

The Donald and The Bern: both men are smart (despite the former insisting on saying it about himself, it happens to be true). Despite “The Apprentice” and the Ivana mess, Trump has to dumb himself down still further (i.e., the “Make America Great Again” baseball cap). So far, the socialist senator from Vermont has refrained from talking American. But for how long? So many pundits, so few who enjoy a Marx-inflected class analysis, I fear he’ll succumb.

Burying the lede as much as I possibly can — in a nation where the life of the mind is valued, this is not considered a vice — this brings us to: Why?

Why are we dumb and proud?

I blame our schools. We learn facts, but not how to think. Rhetoric, debate, logical reasoning are after-school activities. So we grow up believing that everyone is entitled to their opinion, each as valid as any other, even though this cannot possibly be true.

But I could be wrong.

U-S-A! U-S-A!

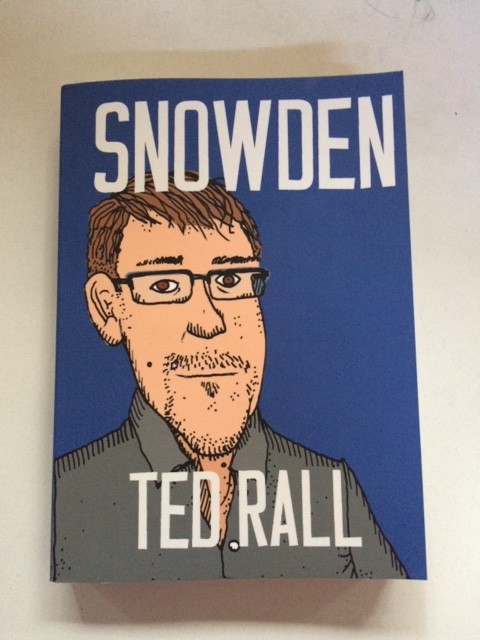

(Ted Rall, syndicated writer and the cartoonist for ANewDomain.net, is the author of the new book “Snowden,” the biography of the NSA whistleblower. Want to support independent journalism? You can subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2015 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

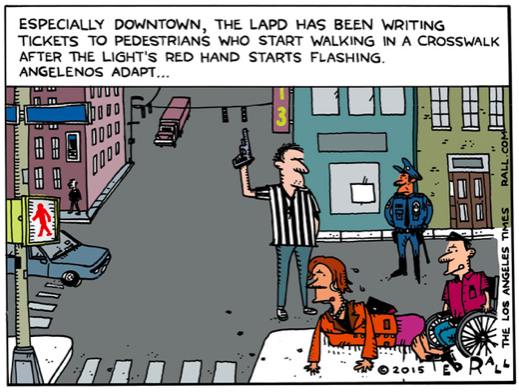

Almost two weeks ago, the LA Times fired me as their editorial cartoonist, where I’d been since 2009.

Almost two weeks ago, the LA Times fired me as their editorial cartoonist, where I’d been since 2009.