People are asking how they can support the fight against the LA Times/LAPD, and police corruption and censorship of the press.

Thank you for asking! I can’t win without you. Here are some ways you can help.

You can sign the petition demanding my reinstatement at the LA Times.

Write a letter to the editor of the LA Times. They haven’t been publishing them, but they do read them.

Keep spreading the word on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Reddit and other social media. Silence and obscurity are the big enemies; powerful institutions like the LAPD and LA Times count on people’s attention spans being short.

Write to media outlets that ought to be covering this story, but haven’t been. Don’t be like the LAPD. Be polite! Prime suspects include:

Charles M. Blow, NY Times columnist

Democracy Now with Amy Goodman

Associated Press

LA Weekly

KFI Radio Los Angeles

NPR Morning Edition

NPR All Things Considered

PBS NewsHour

NPR – On the Media

Columbia Journalism Review

Don’t feel limited by this list. These are just outlets that seem like obvious candidates.

I’ve just lost my job, and legal battles are time-consuming and expensive. If you’d like to help financially, there are several things you can do:

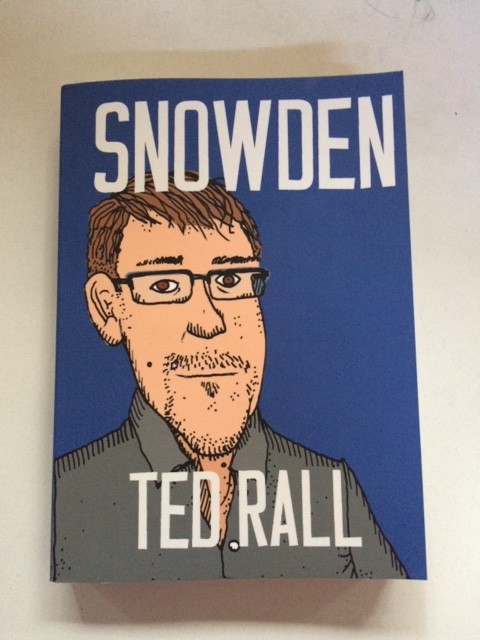

You can buy my new book about Edward Snowden.

Or buy one of my older books.

Or make a tax-deductible donation via the Palast Fund. (Yes, I really do get the money.)

If you’re an editor or know one, you can commission me to draw something, or write something, or speak about something for money. I do all sorts of things! And I’ll travel anywhere. I’ve designed wedding invitations, tattoos, you name it. I need work.