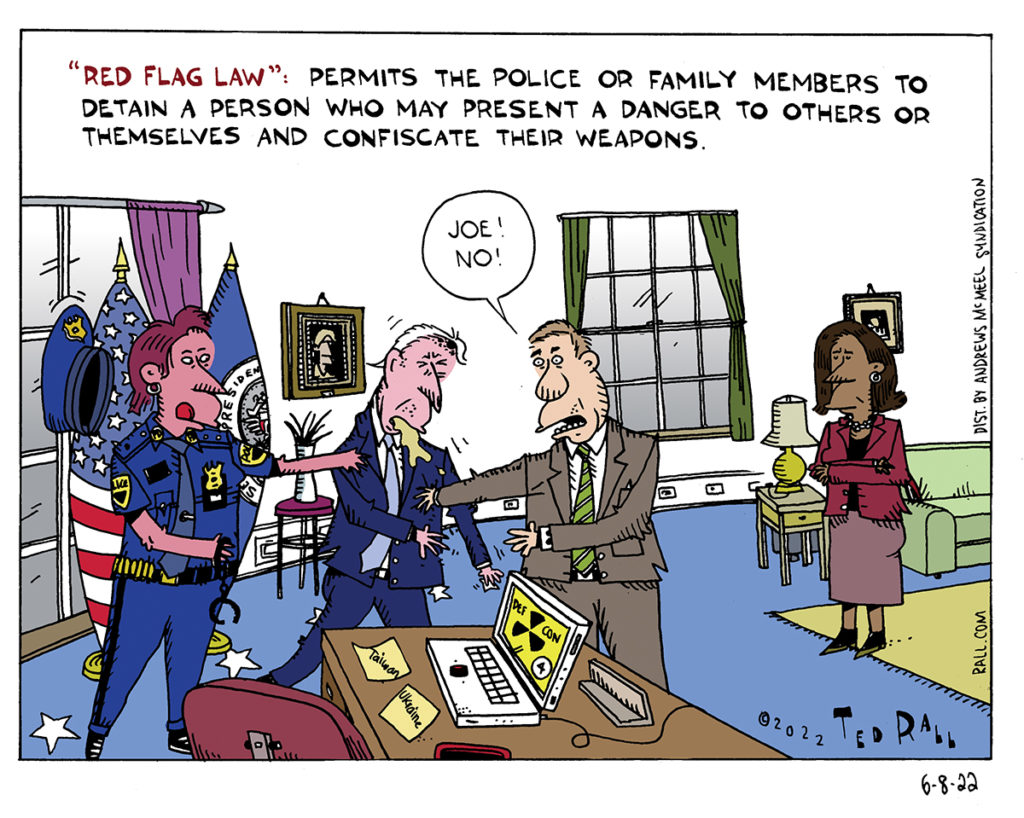

The epidemic of mass shootings has prompted some lawmakers to call for “red flag laws” that would allow people to report those who seem to be getting unhinged before they have the possibility to become a mass shooter. It’s hard to think of a law that could be more easily abused.

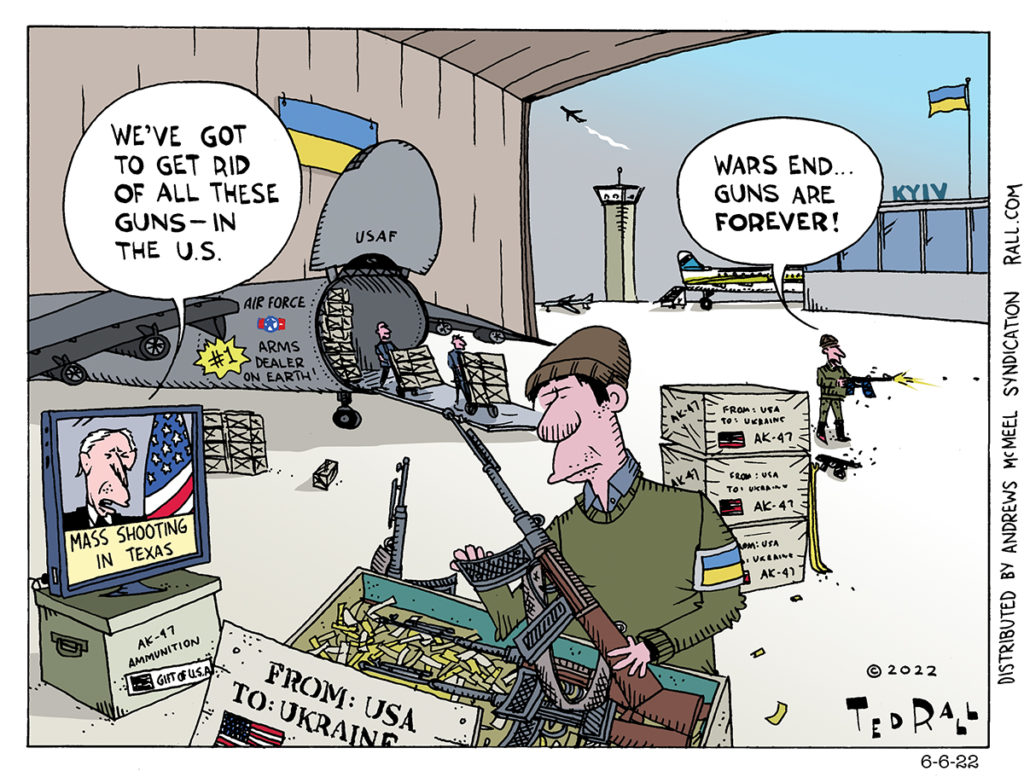

Get Rid of the Guns and Send Them to Ukraine

It shouldn’t be that surprising to President Biden and other Americans that guns are so popular in the United States. After all, the United States is the biggest arms dealer in the world by far. The U.S. recently sent $40 billion in military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine. After the war ends, you can be sure that random violence and terrorism will escalate in a country awash in proxy-supplied weaponry in the same way that it has in places like Afghanistan.

DMZ America Podcast #51: Police Wuss Out in Uvalde. What To Do About Gun Violence. Ukraine Update.

Police are supposed to protect and serve, but apparently all they were good for at the school shooting in Uvalde Texas was standing outside and beating up distraught parents. Why are cops cowards? Ted and Scott have different theories. Can mass shootings be prevented? Probably not, but Scott and Ted have suggestions on ways to mitigate the bloodshed. Finally, the war in Ukraine. Looks like Russia has the upper hand. What’s next?

DMZ America Podcast #49: This Rotten Economy, Ukraine War Propaganda and a Potpourri of Politics

Editorial cartoonist Scott Stantis is back from hiking the Grand Canyon and ready to rumble with fellow cartoonist Ted Rall about inflation, Joe Biden’s sinking approval ratings, that $40 billion we’re sending to Ukraine and a bunch of observations on other stories from this week’s news headlines.

Biden is Giving $40 Billion to Ukraine. Here’s What That Money Could Do Here.

On top of the $2 billion it already sent to Ukraine, the Joe Biden Administration has asked Congress to ignore its previous request for a $10 billion to pay for updated COVID-19 vaccines for American citizens (pandemic? what pandemic?) and send an additional $33 billion to Ukraine instead. The House of Representatives not only obliged, but authorized more than Biden wanted, $40 billion.

The U.S. Congress does this with military spending all the time. They live to please!

Every Democratic congressman voted “yes” to send weapons to a country that has “several hundred monuments, statues, and streets named after Nazi collaborators,” according to The Forward. That even includes AOC’s “Squad,” who claimed to be progressive.

In the Senate, a rare voice of opposition was raised by libertarian Republican Rand Paul. “We don’t need to be the sugar daddy and the policemen of the world,” Paul remarked. For his trouble, Paul was bizarrely accused of “treason” by online commenters who suggested that his surly Kentucky neighbor should assault him again. All Paul wanted was a week to go over exactly where all that money is going.

Whatever you think of the crisis in Ukraine, Paul has a point. A week isn’t going to make any difference. We should distrust bullies who tell us there’s no time to think, hurry up, shut up, do what we tell you. The total lack of debate in Washington, and in the news media, over the quick transfer of $40 billion to a country that is not a U.S. ally, has a grim human rights record and recently banned a bunch of political parties and opposition cable news channels, ought to prompt some sort of discussion. First and foremost, we ought to consider just how much money $40 billion is and what it could do here in the United States, for Americans.

The $40 billion we are sending to Ukraine will not change the outcome of the war. The United States would never commit enough money or ground troops to do that because it would risk World War III with Russia. The $40 billion will buy a lot of weapons and ammunition that will kill Russians and Ukrainians—nothing more, nothing less.

So how much, exactly, is $40 billion?

Here in the United States, here are some of the things that $40 billion could do:

A $2,000 scholarship for every college student.

A $6,000 scholarship for every college student who is officially in poverty.

$72,000 to every homeless person.

$2,400 to every veteran.

$410,000 to every public school.

$1.3 million to every public high school. It could be used to buy books and other equipment, fix broken infrastructure, build something new for the kids. $1.3 million would pay the salaries of 20 new teachers for 10 years.

$500 to each American family. I pledge to use my $500 not to kill any Russians or Ukrainians.

$420 to every cat. That’s a lot of kibble and litter. Cats don’t kill Russians or Ukrainians.

$2 million each to every person wrongfully convicted of a murder they didn’t commit.

Give a new, fully-loaded car to a million people.

Give a sweet, fully-loaded Macbook Pro laptop to 10 million people.

Give a sweet new TV to 100 million people.

Everyone who currently subscribes to Netflix gets three years for free.

Every adult gets a free subscription to the Washington Post digital edition for three years.

Every adult gets 15 free tickets to the actual, real, in-person, not-at-home movies.

$40 billion would repair almost all of the 220,000 bridges in the United States that need to be repaired and replace all of the 79,500 that need to be replaced. Add the $2 billion we already sent to Ukraine and you can delete the word “almost.”

$40 billion would buy Twitter.

$86,000 for everyone raped over the last year.

$7,000 to help the caregivers of everyone suffering from dementia.

It would hire 50,000 journalists for 20 years. There are only 6,500 now.

$4,000 to every self-identified Native American and Alaska Native. It’s not nearly enough considering what has been done to them, but it’s better than the current nothing.

What if, for some strange reason, we don’t want to use that $40 billion to help our own people right here at home, one out of nine of whom is officially poor—some of whom are actually starving? While the inclination to shovel money at other countries while so many of our own citizens are suffering is nearly impossible to understand, some people (the President, several hundred members of Congress) have such a mindset and therefore must be addressed.

If we’re looking for a country in dire need of, and richly deserving of, $40 billion, we need look no further than Afghanistan.

Afghanistan, which the U.S. brutally occupied for 20 years after invading without just cause, is suffering from the biggest humanitarian crisis in the world. Half its population—20 million people—is suffering from “acute hunger,” according to the UN. The nation collapsed because the U.S. pulled the plug on the economy when it withdrew, imposed draconian economic sanctions in a fit of spiteful pique and seized $7 billion in Afghanistan government funds. Biden has promised a little aid, though none has shown up in Kabul.

From the Intercept: “A senior Democratic foreign policy aide, who was granted anonymity to openly share his thoughts on the Biden administration’s actions, said the policy ‘effectively amounts to mass murder.’ According to the aide, Biden ‘has had warnings from the UN Secretary General, the International Rescue Committee, and the Red Cross, with a unanimous consensus that the liquidity of the central bank is of paramount importance, and no amount of aid can compensate for the destruction of Afghanistan’s financial system and the whole macro economy.’”

Democrats recently joined Republicans to vote no on a modest proposal to study the effect of U.S. sanctions against the Afghan people.

Then again, we really do need that COVID money.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of a new graphic novel about a journalist gone bad, “The Stringer.” Order one today. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

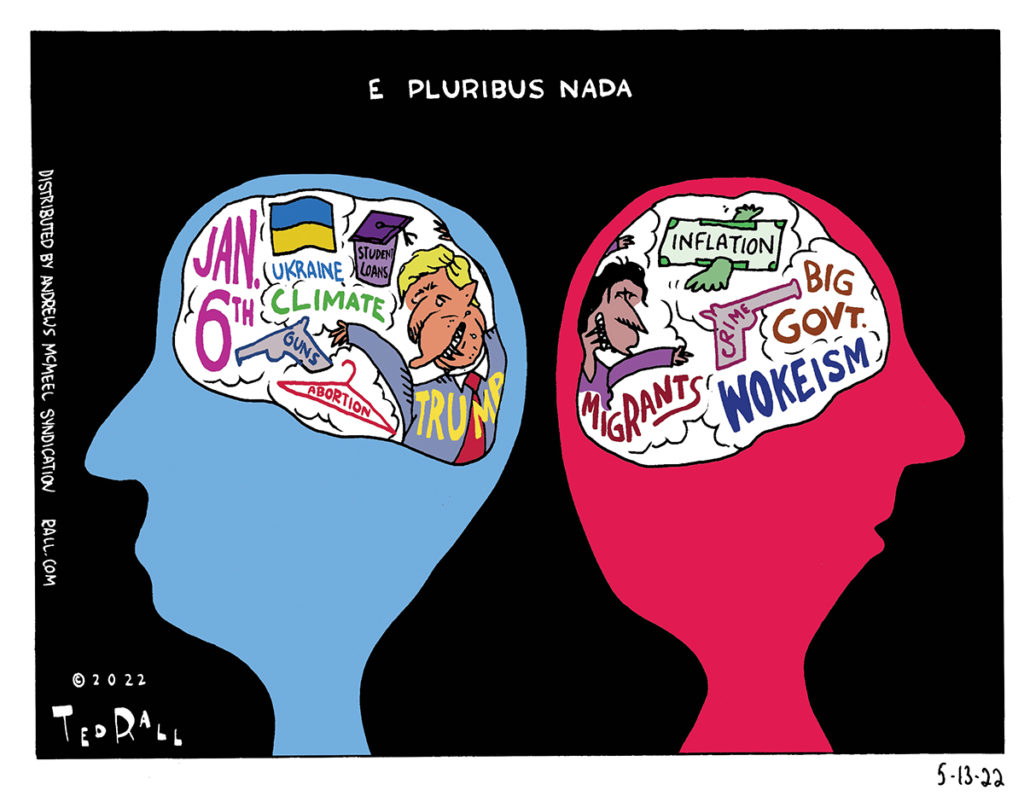

E Pluribus Nada

If a two-party democratic system is to be viable, it has to have a basic shared set of facts, values and issues about which people may differ, and should differ, about solutions. At this point in time, however, the United States doesn’t qualify because the American people are obsessed about totally different things depending on their political orientation.

Wars Make Bad Badfellows

Many Americans are skeptical about military support for Ukraine given that country’s dismal human rights record and autocratic political system. One might also wonder why any other country would want to get into a relationship with the United States.

How the U.S. Lost the Ukraine War

The effect of Western sanctions may cause historians of the future to look upon the conflict in Ukraine as a net defeat for Russia. In terms of the military struggle itself, however, Russia is winning.

Watching American and European news coverage, you might ask yourself how can that be? It comes down to war aims. Russia has them. They are achievable.

The United States doesn’t have any.

“As the war in Ukraine grinds through its third month,” the Washington Post reports, “the Biden administration has tried to maintain a set of public objectives that adapt to changes on the battlefield and stress NATO unity, while making it clear that Russia will lose, even as Ukraine decides what constitutes winning. But the contours of a Russian loss remain as murky as a Ukrainian victory.”

War aims are a list of what one side in a military conflict hopes to achieve at its conclusion.

There are two kinds.

The first type of war aim is propaganda for public consumption. An overt war aim can be vague, as when President Woodrow Wilson urged Americans to enter World War I in order to “make the world safe for democracy” (whatever that meant) or specific, like FDR’s demand for the “unconditional surrender” of the Axis powers. A specific, easily measured, metric is better.

Covert war aims are goals that political and military leaders are really after. A covert war aim must be realistic. For example, contrary to the long-standing belief that he viewed the outbreak of the Korean war as an irritating distraction, Stalin approved of and supported North Korea’s invasion of the South in 1950. He didn’t care if North Korea captured territory. He wanted to drag the United States into a conflict that would diminish its standing in Asia and distract it from the Cold War in Europe. The Soviet ruler died knowing that, whatever the final outcome, he had won.

A publicly-stated war aim tries to galvanize domestic support, which is especially necessary when fighting a proxy war (Ukraine) or war of choice (Iraq). But you can’t win a war when your military and political leaders are unable to define, even to themselves behind closed doors, what winning looks like.

America’s biggest military debacles occurred after primary objectives metastasized. In Vietnam both the publicly-stated and actual primary war aim was initially to prevent the attempted overthrow of the government of South Vietnam and to prevent the spread of socialism, the so-called Domino Theory. Then the U.S. wanted to make sure that soldiers who had died at the beginning of the war hadn’t died in vain. By the end, the war was about leveraging the safe return of POWs. A recurring theme of accounts by soldiers in the jungle as well as top strategists at the Pentagon is that, before long, no one knew why we were over there.

Again, in Afghanistan after 2002, war aims kept changing. Mission creep expanded from the goal of defeating Al Qaeda to apprehending Osama bin Laden to building infrastructure to establishing democracy to improving security to using the country as a base for airstrikes against neighboring Pakistan. By 2009 the Pentagon couldn’t articulate what it was trying to accomplish. In the end, the U.S. did nothing but stave off the inevitable defeat and collapse of its unpopular Afghan puppet regime.

Clear war aims are essential to winning. Reacting to his experience in Vietnam, the late General Colin Powell led U.S. forces to victory in the first Gulf War with his doctrine that a successful military action enjoys strong domestic political support, is fought by a sufficient number of troops and begins with a clear military and political objective that leads to a quick exit. After Saddam Hussein’s forces were routed from Kuwait, George H.W. Bush ignored advisers who wanted to expand the conflict into Iraq. America’s mission accomplished, there was a tickertape parade down Broadway, the end.

The U.S. too often involves itself in foreign conflicts without declaring clear war aims—or even knowing themselves what they are. In Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq, unclear or shifting war aims led to endless escalation followed by fatigue on the home front, declining popular will and defeat. Our involvement in the proxy conflicts in Yemen and Syria also have the character of forever wars, though American voters won’t pay much attention as long as the cost is limited to taxpayer dollars rather than their sons and daughters.

I wrote a piece in 2001 titled “How We Lost Afghanistan.” Given that the U.S. had just overthrown the Taliban, it was cheekily counterintuitive. But I was looking at the Afghan war from the Afghan perspective, which is why I was right and the mainstream media was wrong. I see a similar situation unfolding in Ukraine. We are so misled by our cultural biases that we fail to understand the Russian point of view. The U.S. failure to articulate war aims stems from arrogance. We think we’re so rich and powerful that we can beat anyone, even if our strategy is half-assed and we don’t understand politics on the other side of the planet, where the war is.

President Joe Biden’s approach to Ukraine appears to boil down to: let’s throw more money and weapons into this conflict and hope it helps.

That’s not a strategy. It’s a prayer.

Biden says he wants to preserve Ukraine as a sovereign state and defend its territory. But how much territory? How much sovereignty? Would Biden accept continued autonomy for the breakaway republics in the Dombas? The White House appears unwilling to escalate by supporting an attempt to expel Russian forces from eastern Ukraine, much less Crimea—where they are welcomed by a population dominated by ethnic Russians. Short of a willingness to risk nuclear war, the likely ultimate outcome of the U.S. position will be a Korea-like partition into western and eastern zones. A divided Ukraine would create a disputed border—which would disqualify a rump Ukrainian application to join NATO.

Russia’s primary demand is that Ukraine not join NATO. If America’s goal winds up resolving the main reason President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, why is the U.S. involved? A war aim that neatly aligns with one’s adversary’s is grounds for peace talks, not fighting.

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin recently added a second Ukraine war aim: “We want to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.” Weakened to what extent? Reduced to a failed state? Mildly inconvenienced? Not only is the policy dangerous, it fails to define a clear objective.

Russia, on the other hand, has secured its allies in the autonomous republics and created a buffer zone to protect them. Crimea will remain annexed to Russia. NATO membership for Ukraine, a chimera to begin with, is now a mere fever dream. Unlike the U.S., the Russians declared their objectives and achieved the important ones.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of a new graphic novel about a journalist gone bad, “The Stringer.” Order one today. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

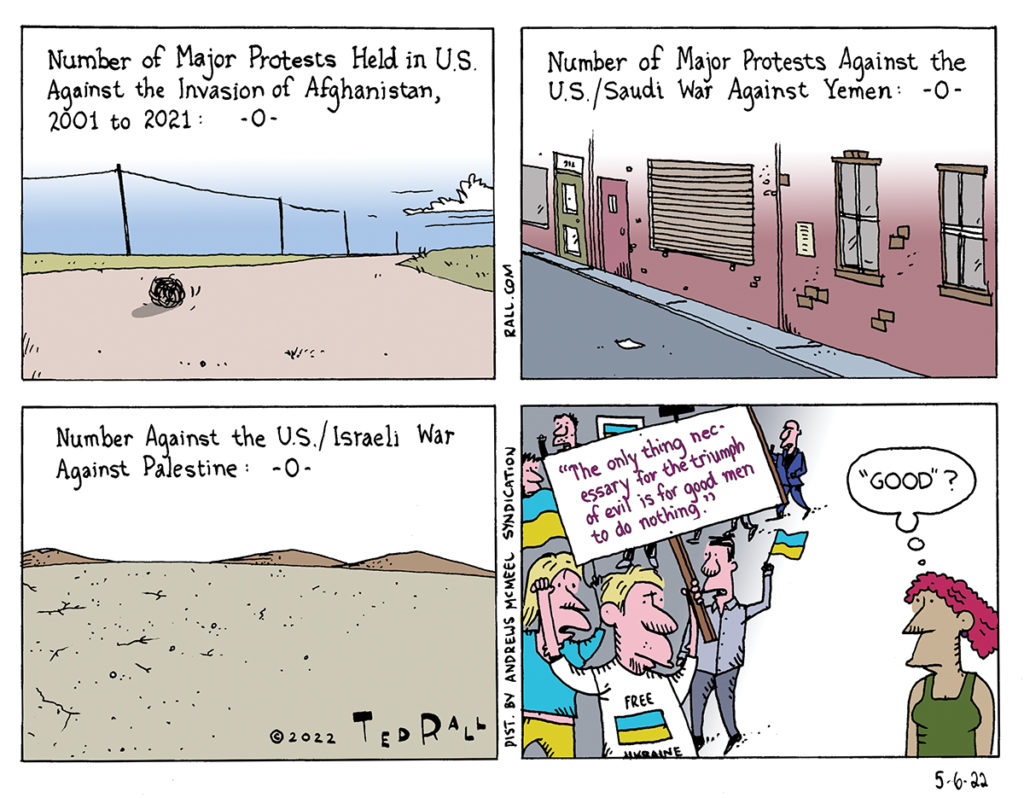

The Only Thing Necessary for Evil to Triumph

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” That statement is often misattributed to Edmund Burke. After Russia invaded Ukraine, many Americans who didn’t have anything to say about the invasion of Afghanistan or Iraq, much less torture at Guantánamo and elsewhere, or Yemen, or Palestine, suddenly started wearing blue and yellow flags. They weren’t good before, so how can these self-serving souls think they are suddenly being good now?

Good Luck with Sanctions

The Russian invasion of Ukraine prompted the usual American response of imposing economic sanctions on Russia and Russian nationals. You only have to look at Cuba and Iran to see how consistently ineffective sanctions are. To the contrary, they tend to increase the popularity of the targeted government as a a siege mentality sets in.