Airing LIVE at 10 am Eastern time this morning, then Streaming 24-7 thereafter:

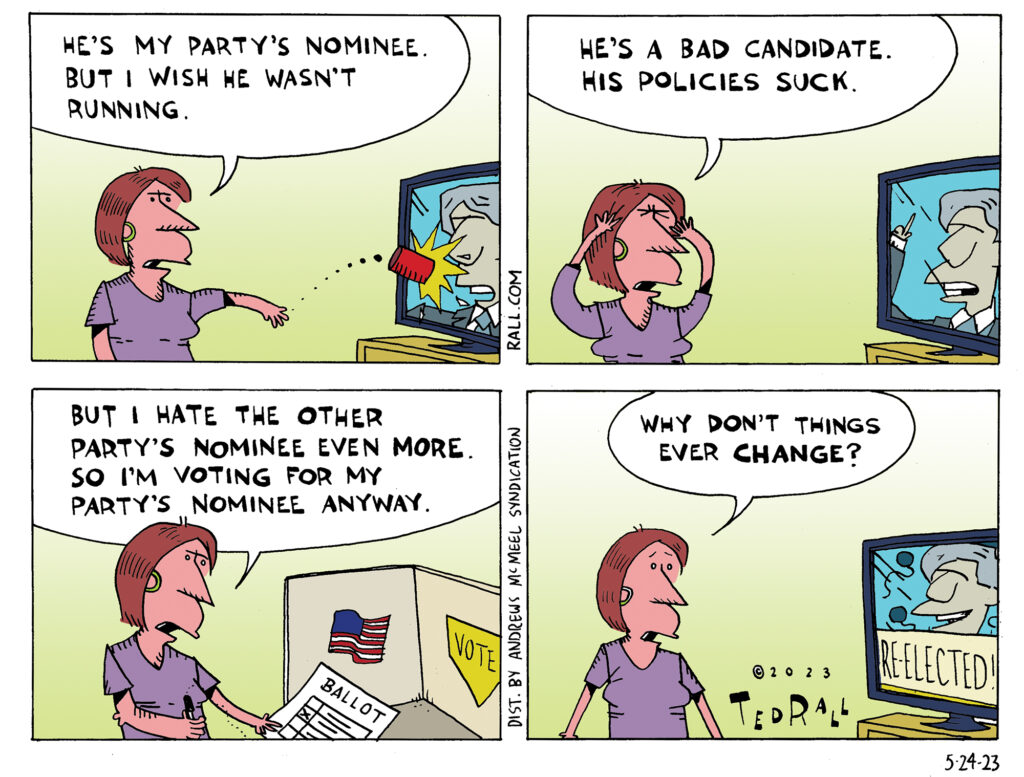

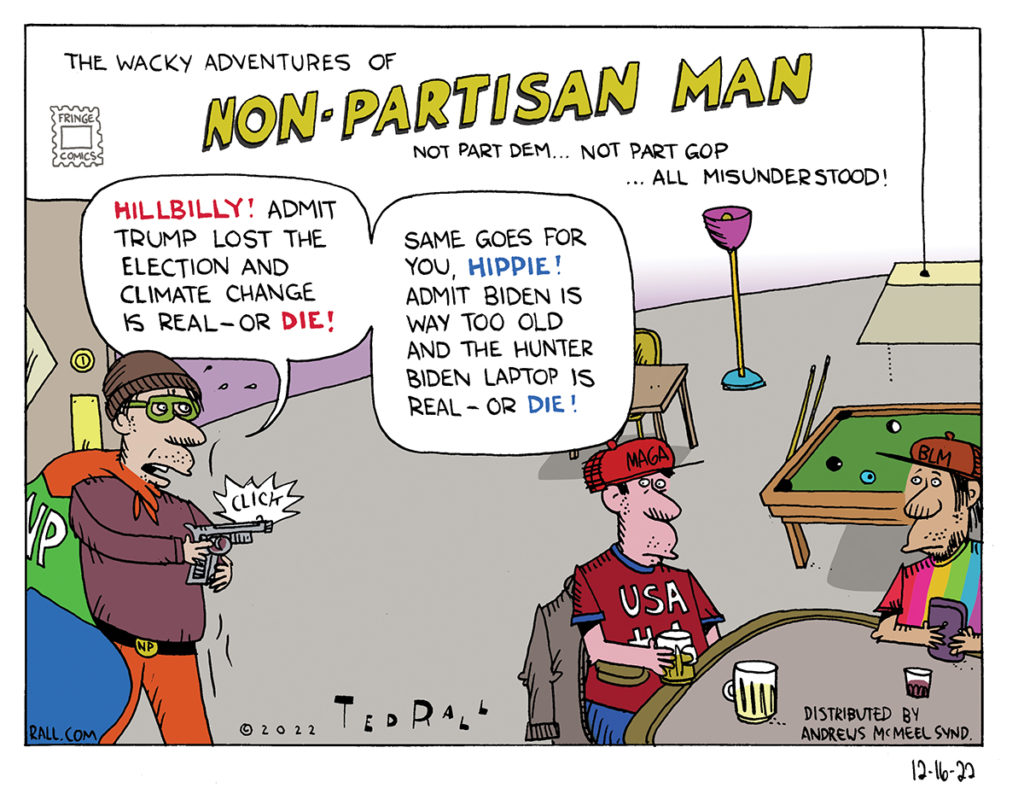

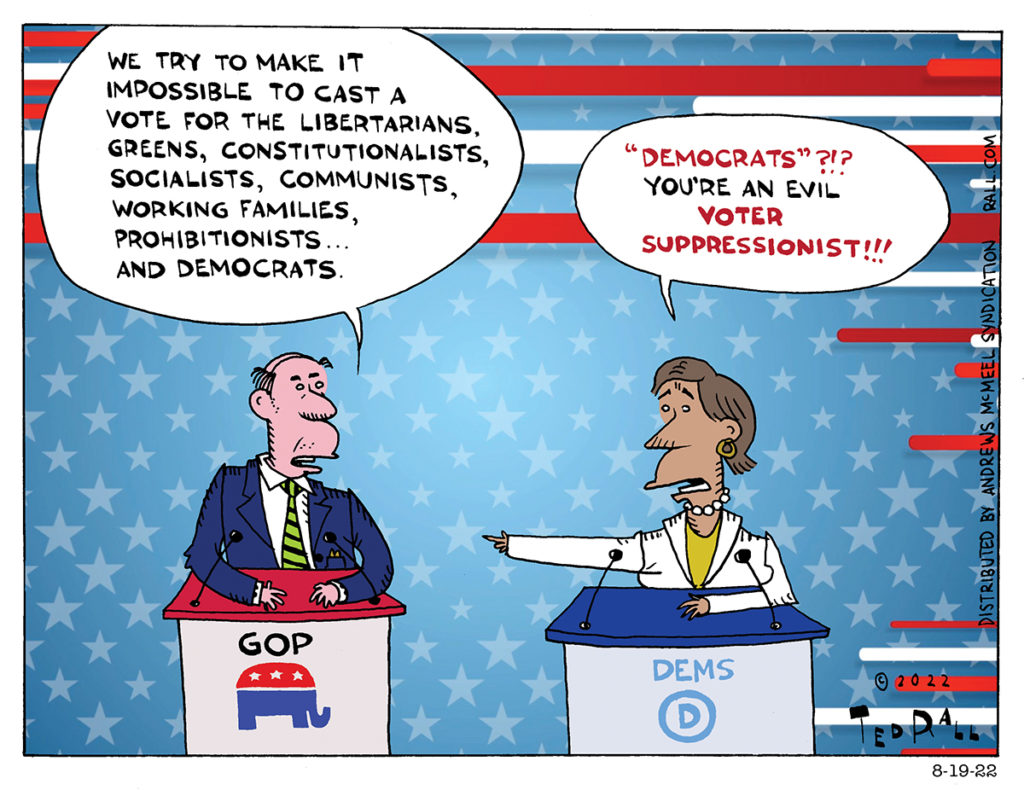

Dispirited and depressed, the Democratic Party doesn’t have a target audience, a message to send it, or a strategy to opposing Trumpism. Highlighting their dismal situation, new ideas were notably missing at a recent election for new DNC chair, where party insiders insisted that Biden and Harris ran great campaigns that failed to get their great message across to the voters and that nothing should fundamentally change. Meanwhile, Trump’s MAGA Republicans are manic and energized, running roughshod over institutional and constitutional norms, and capturing our national attention.

Can a major political party survive without a core constituency or firm ideological underpinning? Is waiting for Trump to overreach, provoke a backlash or die a feasible strategy? Will Democrats go the way of the Whigs?

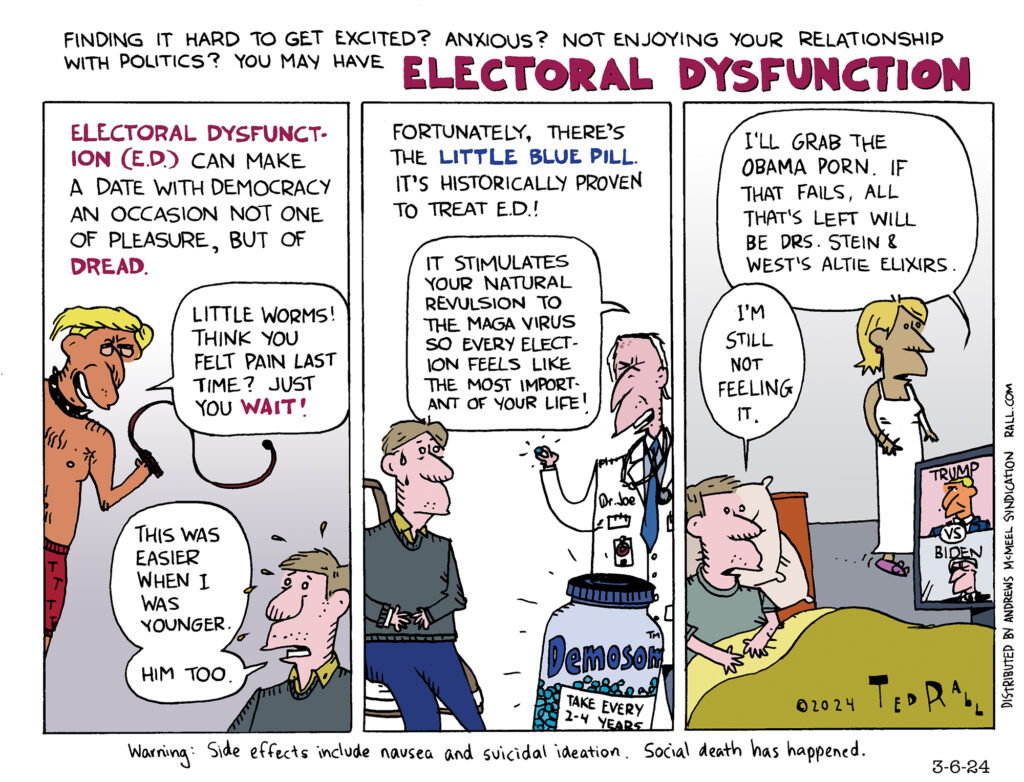

On today’s “The TMI Show,” Manila Chan and Ted Rall discuss the future of the Democratic Party. Does it have one? If so, what does it look like? Joining is guest Scott Stantis, editorial cartoonist for The Chicago Tribune.

Non-voters are the biggest (potential) voting bloc in American politics. In midterm, state and local elections, more eligible voters choose not to exercise their franchise than to do so.

Non-voters are the biggest (potential) voting bloc in American politics. In midterm, state and local elections, more eligible voters choose not to exercise their franchise than to do so.