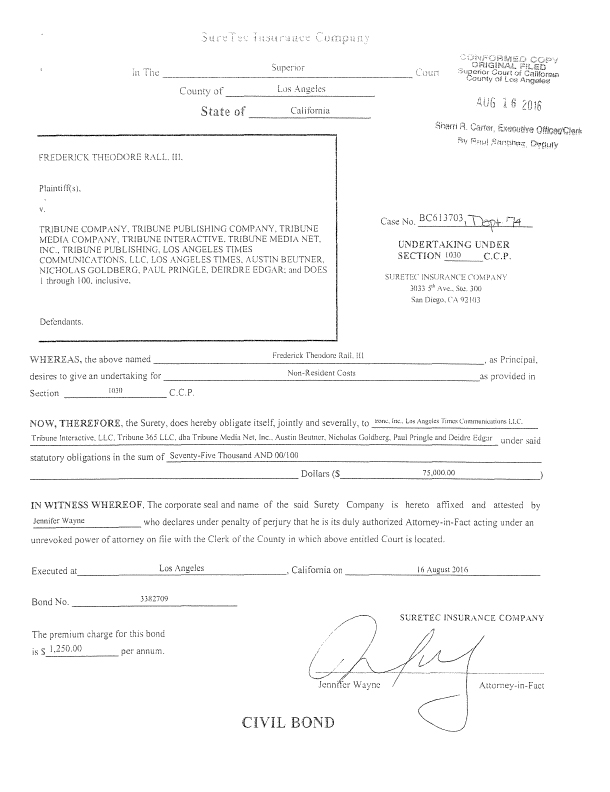

I am suing for the Los Angeles Times and the $638 million newspaper conglomerate Tronc for the defamation and wrongful termination they carried out as a favor for the chief of Los Angeles Police Department.

I don’t know how things will turn out. But I have learned a lot about the justice system.

I’ve learned there’s a “Thin Grey Line” — a conspiracy of silence that media outlets use to shield one another from public scrutiny and accountability. It’s not President Trump’s supposed “fake news.”

It’s No News At All.

A black hole.

If media misconduct falls in the woods, whatever sound it makes receives no coverage in “rival” media outlets.

The Thin Blue Line is a 1988 movie describing how police protect one another from allegations of wrongdoing by clamming up about what they know, leading to the railroading of an innocent man. Similarly, media organizations conspire to keep allegations of libel and other wrongdoing out of the public eye. You don’t cover my bad behavior and I won’t cover yours.

Of course, some libel lawsuits are too big to ignore. In those cases the Thin Grey Line slants their coverage to make the victims look like petulant crybabies or greedy pro-censorship fascists.

I learned about the Thin Grey Line when I reached out to media organizations about my situation with the LA Times. Although certain outlets did a good job covering my case — the UK Guardian and the New York Observer stood out — big papers like the New York Times and Washington Post wouldn’t touch it.

“Cartoonist Critical of Police Fired as Favor to LAPD after LAPD Pension Fund Buys Major Interest in LA Times’ Parent Company” has all the components of a major story: big guy crushes little guy, privacy violations, secret police spying on citizens going back decades, ugly conflicts of interest, a police department pension fund that bought newspaper stock so it could leverage it into editorial control of major newspapers, a criminal conspiracy at the highest levels of local government.

If the villain wasn’t a media company, a media outlet would be all over it.

Most U.S. media outlets ignored my story. Most that put out reports were either online-only or based overseas.

Some, like NPR, explained that my story required investigative reporting for which they didn’t have a budget.

Rall v. Los Angeles Times is a natural fit for The Intercept, the news site dedicated to the Snowden revelations and perfidy by government and the press. Indeed, an Intercept reporter worked the story, spending hours talking to me. Then he took it to his editors — who killed it. Was someone higher on the food chain connected to the Times or LAPD? Were they reluctant to take on a fellow media outlet? All I know is, the guy never called me back. That’s unusual to say the least.

Historically, problems at the local daily newspaper have been red meat to an alternative newsweekly, the scrappy underdog in many metro media markets. New York’s late Village Voice used to love taking on the Times, Post and Daily News. But things are different now. Journalists who follow Los Angeles are shocked that LA Weekly won’t cover my two-year-old lawsuit.

Major libel verdicts against media outlets get buried by the Thin Grey Line. A jury dunned the Raleigh News & Observer $9 million for libel in 2016. Two Cal Coast Weekly writers owe their defamation victim $1.1 million as of 2017. You probably didn’t hear about those.

But you probably did hear about Hulk Hogan’s $140 million libel verdict against Gawker, which put the site out of business. Most coverage bemoaned the supposed effect on press freedom, not Gawker’s crazy decision to publish a video of Hogan having sex or to keep it online after Hogan’s lawyer offered to let the whole thing go for zero cash if Gawker took it down.

Legacy media still hasn’t figured out the Internet. But they’re good at propaganda. Exploiting Trump’s bombastic “fake news” broadsides against the press, they’re casting themselves as party organs of the anti-Trump “Resistance.”

“Democracy dies in darkness,” The Washington Post tells its readers.

“The truth is more important now than ever,” quoth The New York Times.

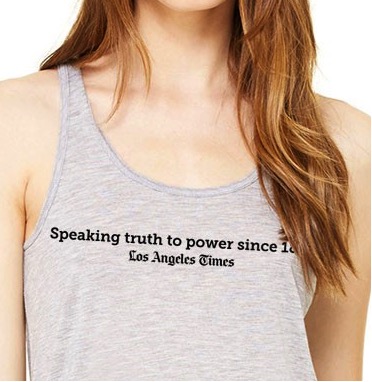

Hilariously, The Los Angeles Times: “Speaking truth to power.” (But not to the chief of police!)

As a journalist and satirist who relies on the First Amendment, I am sympathetic to worries that news outlets might self-censor due to the threat of libel suits. But corporate media looks ridiculous when they portray every defamation and libel plaintiff as sinister threats to press freedom. And it’s downright silly to pretend that every libel and defamation case is inherently frivolous.

“The $140 million payout mandated by a Florida court in Hogan’s privacy case against Gawker, which was bankrolled by Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel, was a chilling development for media companies that are already battling to keep costs down,” Keith Gessen wrote in Columbia Journalism Review.

Nowhere in Gessen’s piece did he mention that Gawker could have saved every penny of that $140 million by exercising a modicum of editorial judgment. Or that Thiel’s role merely leveled the playing field between an individual and a (then-) deep-pocketed media outlet.

The Hogan verdict is only “chilling” to publications so arrogant and stupid as to fight for the right to gratuitously publish material that can ruin a person’s life — material with zero news value — without a legal leg to stand on.

Based on the coverage of the Gawker-Hogan coverage I’ve read since the 2016 verdict, most media outlets are still pushing the Thin Grey Line narrative that Hogan had no grounds to complain. I say that Hogan has the right not to have his sex acts posted to the Internet without his permission.

Thin Grey Line aside, I bet most people agree with me.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of “Francis: The People’s Pope.” You can support Ted’s independent political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)