Monday was Memorial Day, when Americans are supposed to remember military veterans, particularly those who made sacrifices — lives, limbs, sanity — fighting our wars.

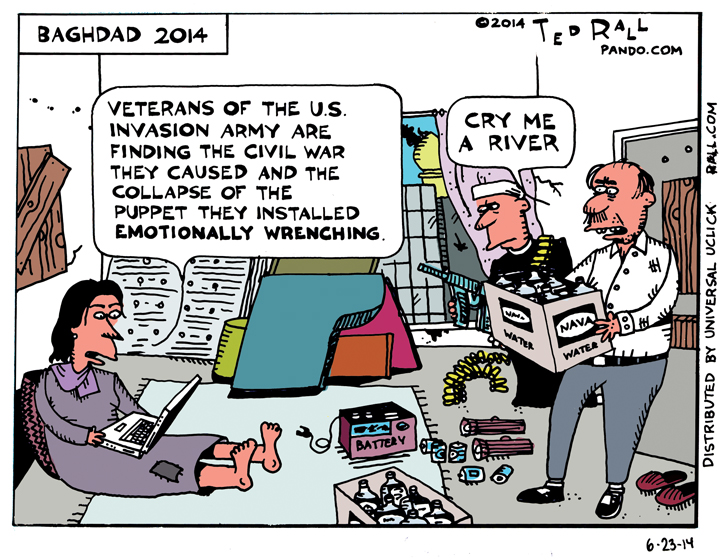

As usual, rhetoric was abundant. People hung flags. Some placed flowers on military graves. There were parades, including one in which a reporter got hit by a drone. President Obama added an oddly pacifist twist to his annual speech, noting that it was “the first Memorial Day in 14 years that the United States is not engaged in a major ground war.”

Excuse me while I puke.

Talk is nice, but veterans need action. Disgusting but true: when it comes to actual help —spending enough money to make sure they can live with dignity — talk is all the U.S. has to offer.

It isn’t just last year’s scandal at the Veterans Administration, which made vets wait for ages to see a doctor, then faked the books to make itself look responsive — and where a whopping three employees lost their jobs as a result. The Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that more than 57,000 homeless veterans, some just poor, others suffering from mental illness, sleep on the street on any given night.

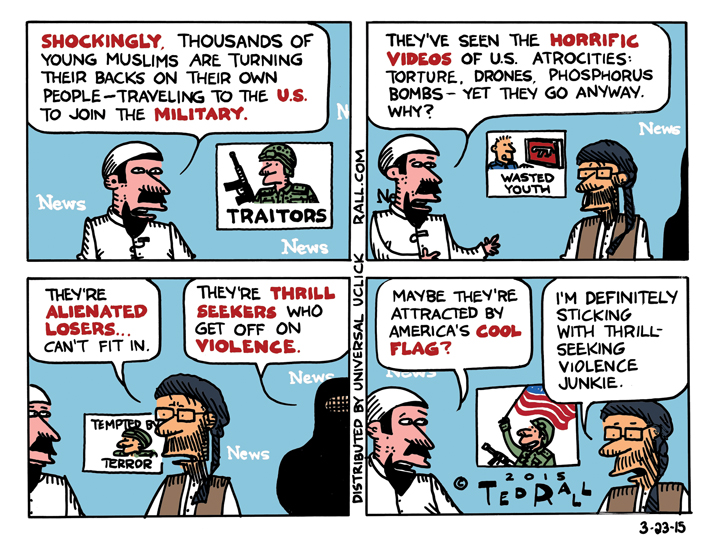

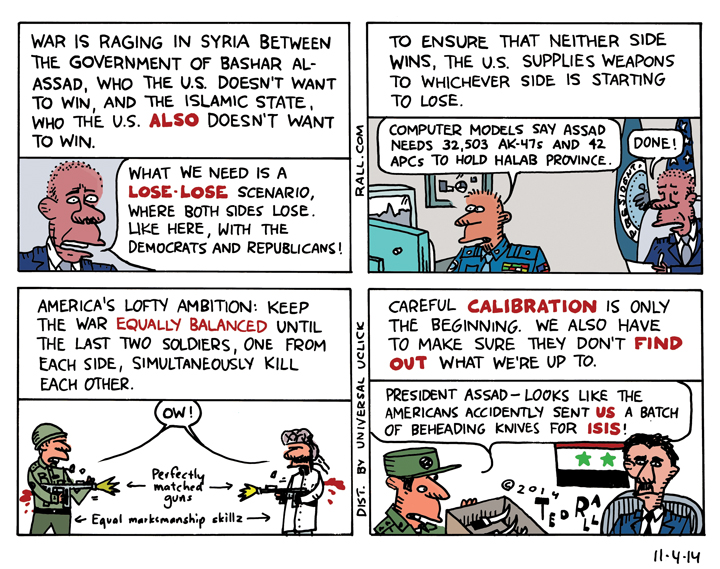

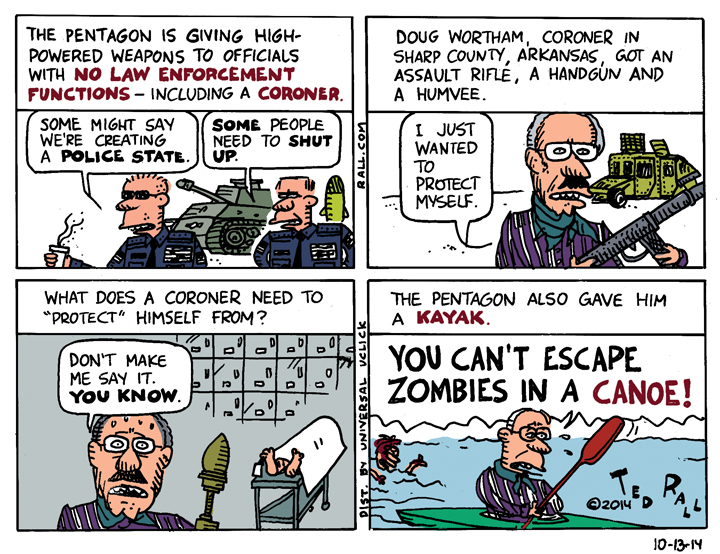

The Pentagon can easily afford to solve these problems. But vets aren’t a spending priority. New wars are. For example, we’re fighting a $40 billion-a-year air campaign against ISIS, although the Islamic State can’t attack the U.S. $40 billion is enough to buy every homeless veteran a $700,000 house.

What you might not know is that this isn’t new.

The U.S. has consistently and ruthlessly screwed vets since the beginning. At this point, army recruiters should thank the heavens that American schools don’t teach history; if they did, no one would enlist.

During the Revolutionary War, officers had been promised a pension and half pay for life. After the British were defeated in 1783, however, Congress reneged on its pledge and issued checks for five years pay, period. “If officers felt cheated, enlisted men felt absolutely betrayed…the common soldier got a pat on the back and a shove out the door,” wrote the historian Andrew C. Lannen. “Some soldiers were given land warrants, but it took many years before they became redeemable. “Impoverished veterans in dire need of cash sold them for pennies on the dollar to investors who could afford to wait several years to collect at full value.”

For more than half a century after beating the British, veterans of the War of 1812 got nothing. Finally, as part of a payout to vets of the Mexican War of 1846-1848 — who themselves were made to wait 23 years — the 1812 vets received service pensions in 1871. By then, many had died of their injuries or old age.

Union troops won the Civil War, but that didn’t stop the government from cheating them out of their benefits too. By the end of 1862, the military was only making good on 7% of claims filed by widows and orphans of the fallen. At least 360,000 Union soldiers were killed, leaving close to a million survivors. But 20 years after the war, the pension office only acknowledged receiving 46,000 applications — less than 5% of those eligible.

Though fading from historical memory, the “Bonus Army” was perhaps the most famous example of the American government’s poor treatment of its war heroes.

Repeating the Revolutionary War policy of “I will gladly pay you a thousand Tuesdays from now for your cannon-fodder corpse today,” Congress awarded veterans of World War I service certificates redeemable for pay plus interest — in 1945, more than two decades later. The Great Depression prompted impoverished vets to form a proto-Occupy movement, the Bonus Expeditionary Force.

In 1932, 43,000 Bonus Army members, their families and supporters camped out in Washington to demand that Congress issue immediate payment in cash. Two generals who’d later become notorious hardasses during World War II, Douglas MacArthur and George Patton, led troops to clear out the camps, shooting, burning and injuring hundreds of vets, whom MacArthur smeared as “communists.” Eighteen years after the end of World War I, in 1936, Congress overrode FDR’s veto and paid out the Bonus.

Even those who served in the so-called “good war” got cheated. “According to a VA estimate, only one in seven of the survivors of the nation’s deceased soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines who likely could qualify for the pension actually get the monthly checks,” reported The Charlotte Observer in 2005. These nearly two million survivors include those whose spouses and parents served in World War II, as well as Korea and Vietnam.

Remember this the next time you hear some politician or their media allies claim to “support our troops.”

Support? They don’t even pay them enough to let them sleep inside.

(Ted Rall, syndicated writer and the cartoonist for The Los Angeles Times, is the author of the new critically-acclaimed book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan.” Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2015 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM