Some “deep green” environmentalists believe that the tab for two-plus centuries of industrialization is about to come due in the form of a catastrophic ecological disaster — one that might lead to the great sixth mass extinction on a scale similar to the meteor believed to have taken out the dinosaurs. (Yes, that means you, human reader.)

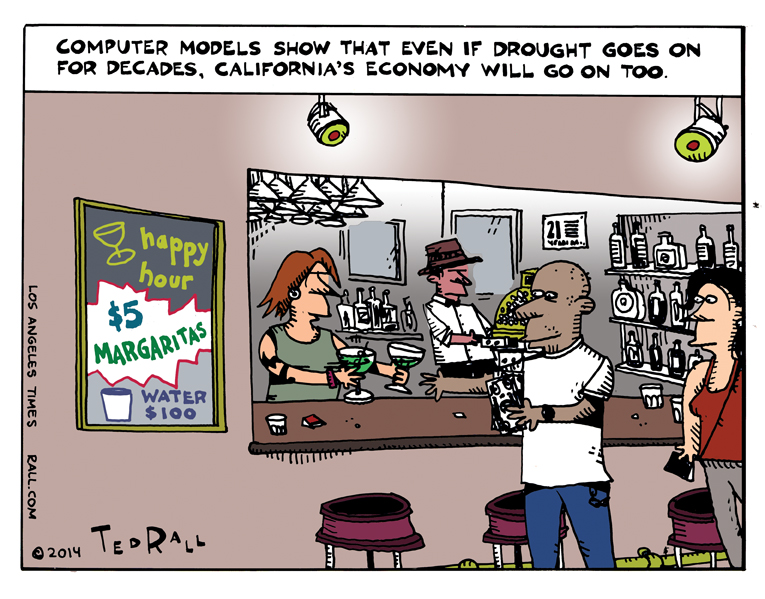

Here in California, the current drought — which some scientists believe may be the worst in 500 years — understandably leaves many Golden State residents, always aware of water restrictions in a region surrounded by deserts, with a sense of disquiet. What if this goes on? Will the California Dream turn to dust and blow away?

Apparently not. Like the Earth in general, California’s climate is surprisingly resilient, according to recent computer models.

State climate researchers ran a projection of what would happen after “even decades of unrelenting mega-drought similar to those that dried out the state in past millennia,” reports Bettina Boxall of the Times.

“The results were surprising,” Jay Lund of UC Davis told her.

If you own stock in the ag business, you might want to consider unloading them. Agriculture, the climatologists found, would be hit hard. “In their computer simulation, annual runoff into rivers and reservoirs amounted to only about half the historical average. Most reservoirs never filled. Under that scenario, experts say, irrigated farm acreage would plunge…The state’s 8 million acres of irrigated cropland could fall by as much as half, predicted Daniel Sumner, director of the University of California Agricultural Issues Center. Farmers would largely abandon relatively low-value crops such as cotton and alfalfa and use their reduced water supplies to keep growing the most profitable fruits, nuts and vegetables. They would let fields revert to scrub or dry-farm them with wheat and other crops that predominated before California’s massive federal irrigation project transformed the face of the Central Valley in the mid-20th century.”

Biodiversity would suffer too. “Aquatic ecosystems would suffer, with some struggling salmon runs fading out of existence.”

Water prices will rise. Desalination plants will be built along the coast. While initially painful, the agrishock would only affect 4% of the state’s economy — notable, but not fatal.

Bottom line: “The California economy would not collapse. The state would not shrivel into a giant, abandoned dust bowl. Agriculture would shrink but by no means disappear.”

Paradoxically, this good news (or not-that-bad news, anyway) is bad news.

Political and economic leaders tend to ignore problems before they turn into a crisis — especially when heading off the issue would cost money. The news that California’s drought probably won’t lead to ruin within their lifetimes, or our children’s lifetimes, ensures that they’ll keep ignoring environmental destruction. Species will keep going extinct. Flocks of birds will continue to thin out. Invasive species will accelerate the process. These things may not sink the Dow Jones Industrial Average, but they really really really suck.

This is one of those rare times when I wish — almost — that the scientists had lied about what they discovered.