Still think the United States is governed by decent people? That the system isn’t totally corrupt and obscenely unfair?

Two stories that broke April 23rd ought to wake you up.

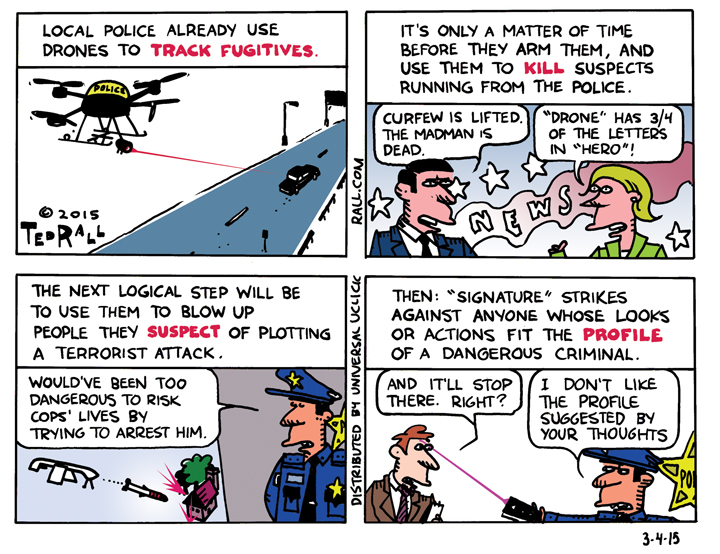

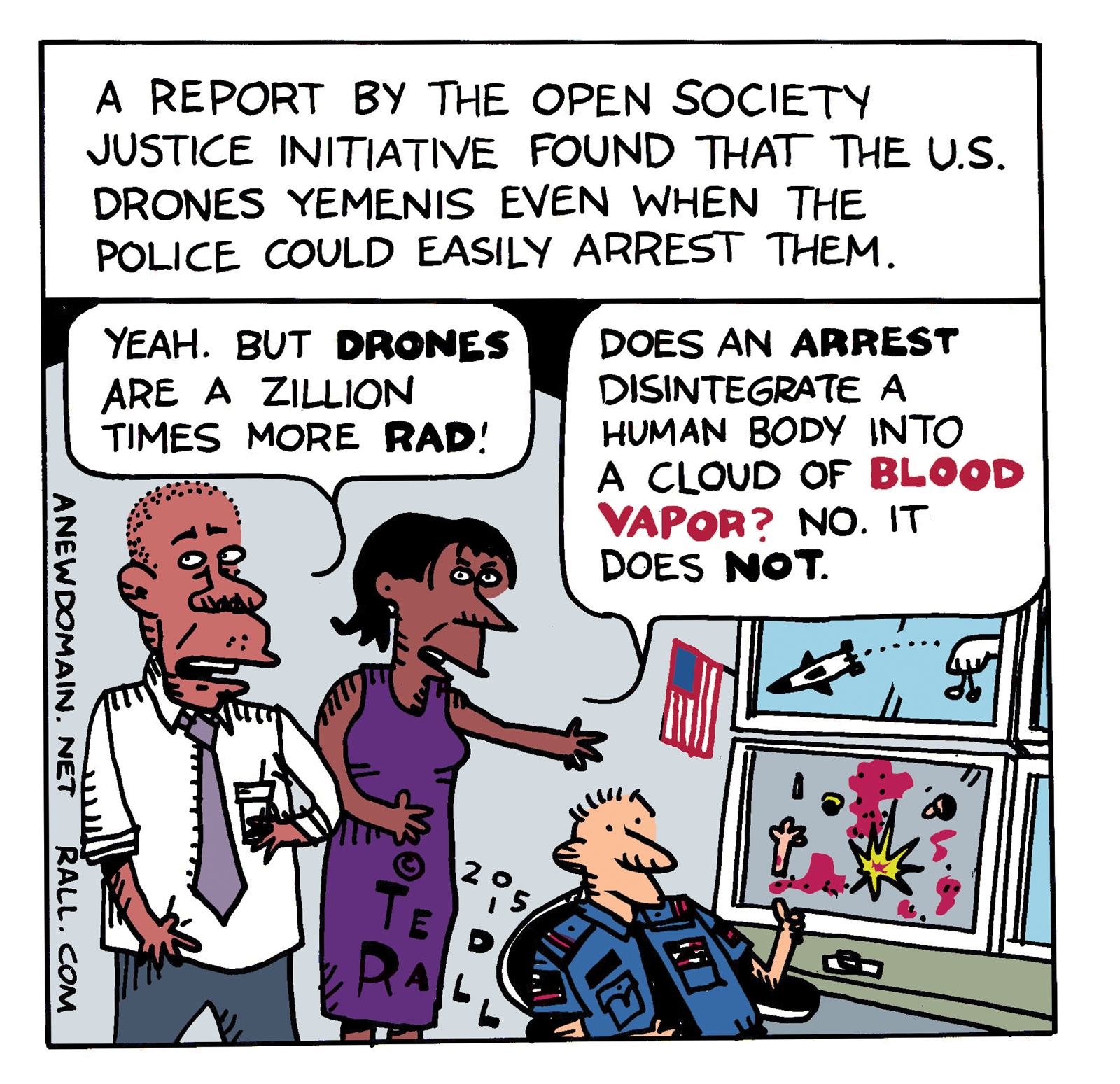

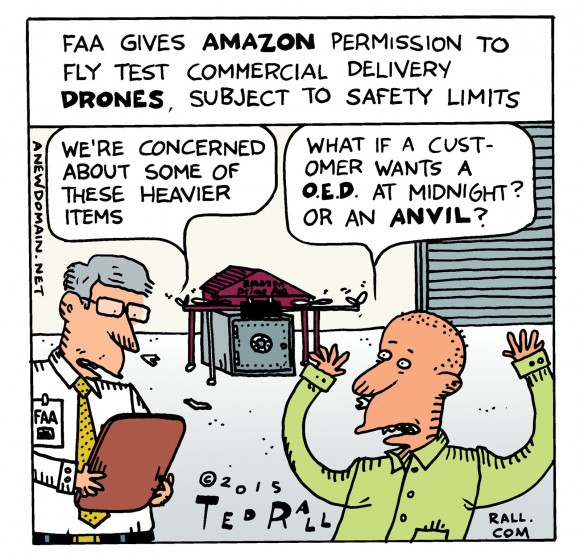

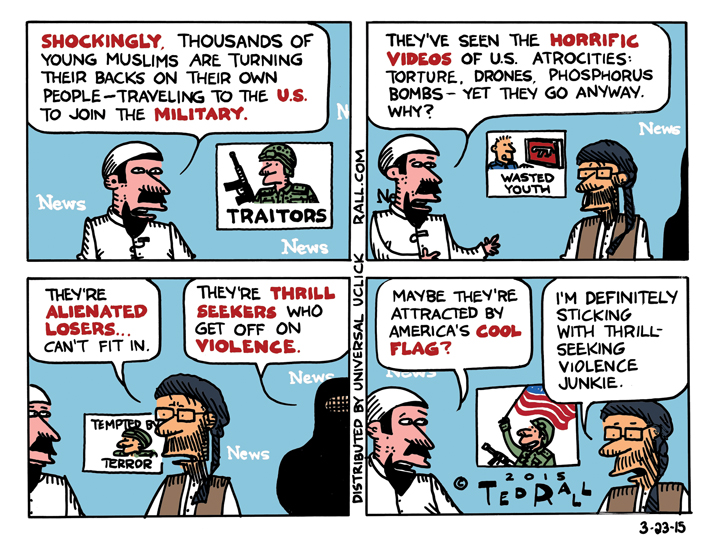

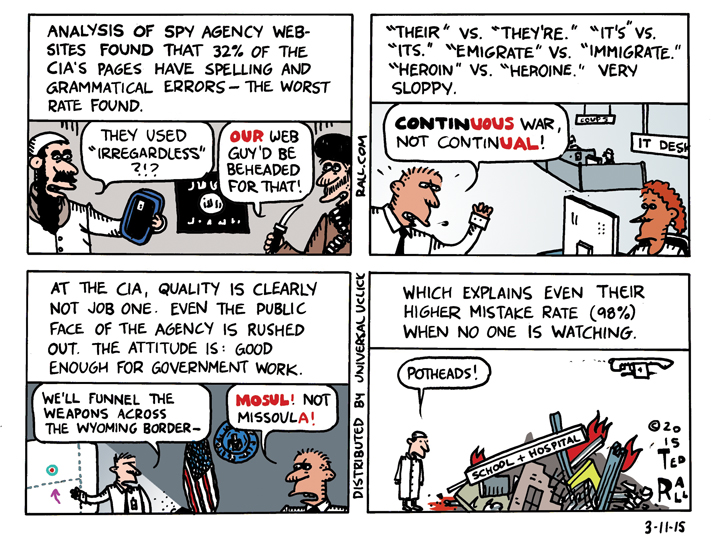

Story 1: President Obama admitted that one of his Predator drones killed two aid workers, an American and an Italian, who were being held hostage by Al Qaeda in Pakistan. As The Guardian reports, “The lack of specificity [about the targets] suggests that despite a much-publicized 2013 policy change by Barack Obama restricting drone killings by, among other things, requiring ‘near certainty that the terrorist target is present,’ the U.S. continues to launch lethal operations without the necessity of knowing who specifically it seeks to kill, a practice that has come to be known as a ‘signature strike.'”

“Lack of specificity” is putting it mildly. According to a report by the group Reprieve, the U.S. targeted 41 “terrorists” — actually, enemies of the corrupt Yemeni and Pakistani regimes — with drones during 2014. Thanks to “lack of specificity,” a total of 1,150 people were killed. Which doesn’t even include the 41 targets, many of whom got away clean.

Obama’s hammy pretend grief was Shatner-worthy. Biting his lip in that sorry/not sorry Bill Clinton way, the president summed up mock sadness for an event that happened back in January. Come on, dude. You seriously expect us to believe you’ve been all weepy for the last three months, except for all those speeches and other public appearances in which you were, you know, laughing and cracking jokes?

Including, um, the same exact day when he pretend-sadded, when he yukked it up with the Super Bowl champion New England Patriots? “That whole story got blown a little out of proportion,” he jibed. (Cuz: “deflate-gate.”) While sad. But laughing.

So. Confusing.

I swear, the right-wing racists are right to hate him. But they hate him for totally the wrong reasons.

Anyway, what took so long for the White House to admit they killed one of our best citizens? “It took weeks to correlate [the hostages’] reported deaths with the drone strikes,” The New York Times quoted White House officials. But in his prepared remarks, Obama said “capturing these terrorists was not possible” — thus the drone strike.

How stupid does the Administration think we are?

The fact that it is possible to find out who dies in a drone fact (albeit after the fact) indicates that there is reliable intelligence coming out of the targeted areas, presumably provided by local police and military sources. If there are cops and troops there who are friendly enough to give us information, then it obviously is possible to ask them to capture the targeted individuals.

Bottom line: the U.S. government is blowing up people with drones willy-nilly, without the slightest clue who they’re blowing up. Which, as political assassinations, are illegal. And which they specifically said was what they were no longer doing. Then they have the nerve to pretend to be sad about the completely avoidable consequences of their actions. They’re disgusting and gross and ought to be locked in prison forever.

Story 2: David Petraeus, former hotshot media-darling general of the Bush and early Obama years, received a slap on the wrist — probation plus a $100,000 fine — for improperly passing on classified military documents to unauthorized people and lying about it to federal agents when they questioned him about it.

Here we go again: more proof that, in the American justice system some people fly first-class while the rest of us go coach.

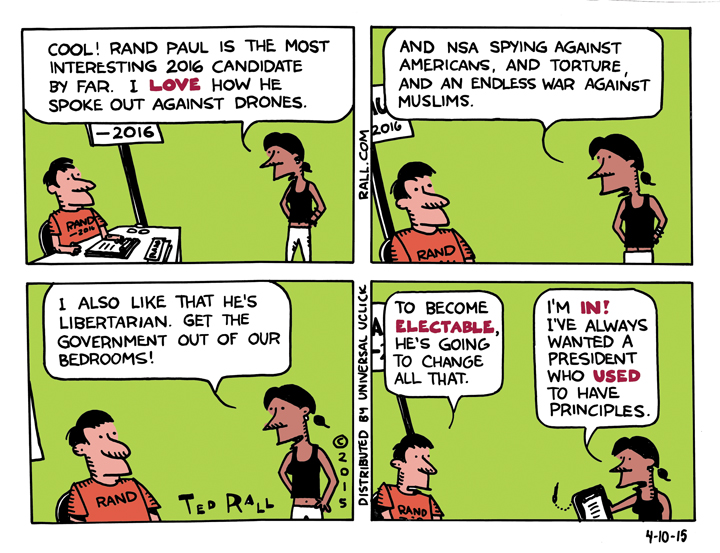

In this back-asswards world, people like Petraeus who ought to be held to the highest standard because they were entrusted with immense power and responsibility, walk free while low-ranking schlubs who committed the same crime get treated like Al Capone. Private Chelsea Manning, who released warlogs documenting U.S. war crimes in Iraq to Wikileaks, rots in prison for 35 years. Edward Snowden, the 31-year-old systems administrator for a private NSA outsourcing firm who revealed that the U.S. government is reading all our emails and listening to all our phone calls, faces life in prison.

Two years probation. Meanwhile, teachers who helped their students cheat on standardized tests got seven years in prison. To Petraeus, who went to work for a hedge fund, $100,000 is a nice tip for the caddy.

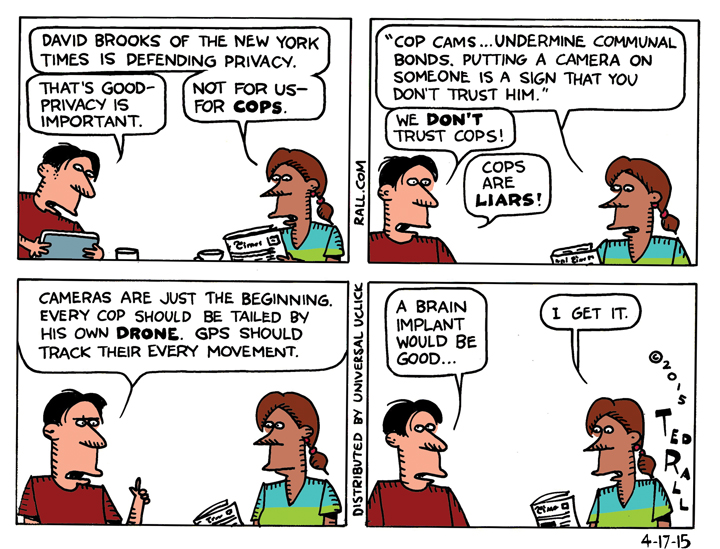

Adding insanity to insult is the fact that Petraeus’ motive for endangering national security was venal: he gave the documents to his girlfriend, who wrote his authorized biography. Manning and Snowden, heroes who in a sane society would receive ticker-tape parades and presidential medals of freedom, weren’t after glory. They wanted to inform the American people about atrocities committed in their name, and about wholesale violations of their basic freedoms, including the right to privacy.

Before he was caught and while he was sharing classified info with his gf, Petraeus had the gall to hypocritically pontificate about a CIA officer who disclosed sensitive information. Unlike Petraeus, the CIA guy got coach-class justice: 30 months in prison.

“Oaths do matter,” Petraeus pompously bloviated in 2012, “and there are indeed consequences for those who believe they are above the laws that protect our fellow officers and enable American intelligence agencies to operate with the requisite degree of secrecy.”

If you’re a first-classer, the consequences are very small.

(Ted Rall, syndicated writer and the cartoonist for The Los Angeles Times, is the author of the new critically-acclaimed book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan.” Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2015 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

At worst, drone operators report being mind

At worst, drone operators report being mind