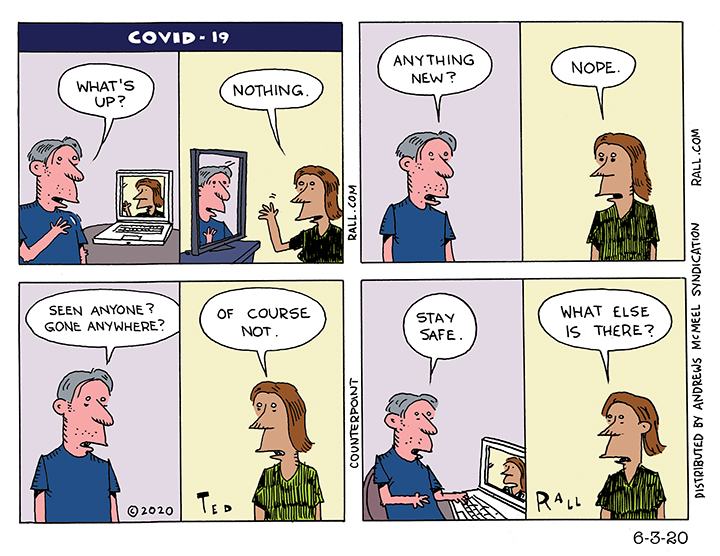

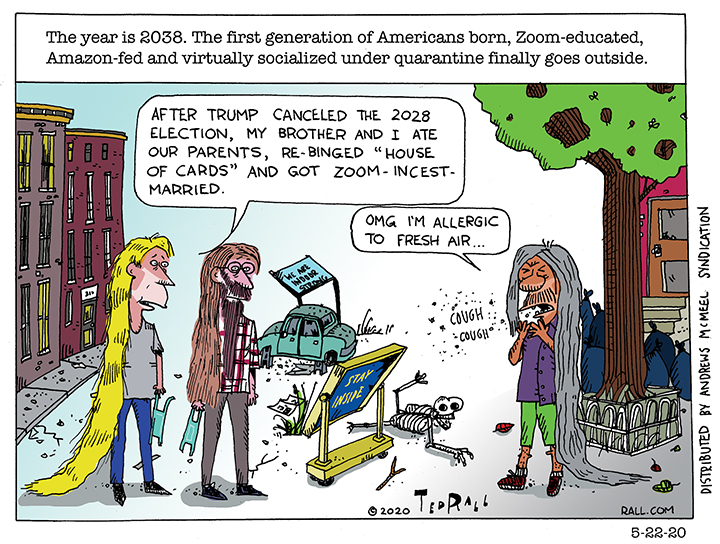

The word “quarantine” comes from the Italian term for 40 days because that was the longest time that people were believed to be able to withstand lockdown before they started to lose it. Now we are starting to see why. Is it really life if you can’t live it?

Did I or Didn’t I Have COVID-19? Blundering through Unknowable Truths

Few things are more terrifying than the unknown, as we are discovering as we struggle to navigate, avoid and (if we fail) survive a mysterious new virus. That goes double when reliable information is hard to come by; it is unquantifiably worse without credible leadership.

“Who ya gonna believe,” Chico Marx asked, “me or your own eyes?” More than other cultures of which I am aware, Americans are acculturated to ignore their instincts and the truth of their observations. A smoker might wake up coughing up phlegm every morning for decades yet he only begins to internalize that tobacco is dangerous to his health after a surgeon general he has never met issues a report. You might live in the same house years on end but discount your observation of the fact that it used to snow but now it doesn’t; global warming only becomes official when hundreds of climate scientists certify what you already knew.

Sometimes you have to trust yourself.

Even when you are mistaken about some details.

I’m 90% sure that I had COVID-19. It was in November. I was in LA for several weeks. In March I blogged about my symptoms: “I had an incessant dry cough…I had a constant fever. My temperature ranged from about 101° during the day to closer to 103° at night. My chest was tight: it felt like a car was parked on it. I had absolutely no energy whatsoever. I was exhausted. Even walking half a block, I had to take a break. I would get back to my hotel after a meeting and be asleep by 6 PM. I would sleep 14 hours and wake up still wiped out. ‘What the hell,’ I would ask myself, ‘is going on?’”

I tested negative for influenza. An x-ray revealed early-stage pneumonia. I was prescribed antibiotics and a nebulizer. Obviously I recovered; here I am writing this. But I’m still weak and tired.

If I could prove I had the novel coronavirus in November, it might be a news story. Aside from a New Jersey mayor who says he is sure that he had COVID-19 in November and a 55-year-old Chinese man whom doctors say had the disease on November 17th, the scientific and journalistic consensus is that the coronavirus pandemic originated in Wuhan, China in December. Last week my physician administered a serology test to determine if I have antibodies consistent with past infection with SARS-CoV-2. It came back negative. I was puzzled. If I hadn’t had COVID-19, or the flu, what the hell was this horrible illness?

I’m 56. I’ve had trouble with my lungs my entire life: asthma, lots of bronchitis, several cases of pneumonia, swine flu. My symptoms are remarkably consistent. My November experience was nothing like anything before. What bronchitis gives you fever for weeks at a time? What pneumonia?

The day after my doctor called with the negative antibody test result, the FDA issued a statement essentially declaring such lab tests worthless for the purpose of figuring out whether you’ve ever had COVID-19. So even if it had come back positive, it wouldn’t have meant anything.

Even if my test had been 100% reliable, and it had come back positive, all the test result would have proven is that I had COVID-19 at some point. It would not have evidenced that I contracted COVID-19 in November. I could have caught something else in November and COVID-19 asymptomatically, later.

Further reducing my reliability as a possible COVID-19 Patient Zero is a failure of memory: in my blog, I wrote—because I believed it—that this happened in January. When I subsequently reviewed my records, I came across a photo selfie of me on the nebulizer in a West Hollywood urgent care clinic. It was dated November 15th and I had already been sick for a couple of weeks. You may be less surprised that I made such a mistake when I tell you that my mom was desperately ill at the time, and she died on February 7th after a year of hell. Whatever it was, COVID-19 or something else, definitely happened in November.

Does it matter? Scientifically of course the answer is yes. Epidemiologists benefit when they can trace a viral pandemic to its roots. Personally, medically, probably. Though the experts remain officially uncertain whether someone can be reinfected by COVID-19, the evidence appears to say that COVID-19 survivors probably cannot get reinfected to a significant extent. It wouldn’t prompt me to go out in public without a mask or stop washing my hands. I know it’s selfish but I won’t deny it: I would love the peace of mind of knowing that this particular beast isn’t going to kill me. And I would like to donate blood for use as plasma in order to treat coronavirus victims.

As it stands, most of my thoughts on this subject are a muddled rumination about the nature of humanity and the reliability of personal knowledge. If I were an animal, and had never heard of science, and had memory and self-awareness, I would know—know with the same certainty that I know I am typing this column—that I had COVID-19 and that I should probably worry about something else more than the possibility that I might get it again. But I am not an animal, I am an American filled with self-doubt, in awe of Science and the desire to document what can probably never be proven and that in fact might not be true at all.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of the biography “Bernie,” updated and expanded for 2020. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

We Need a Centralized Medical System Too

The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare two fundamental flaws in the American healthcare system.

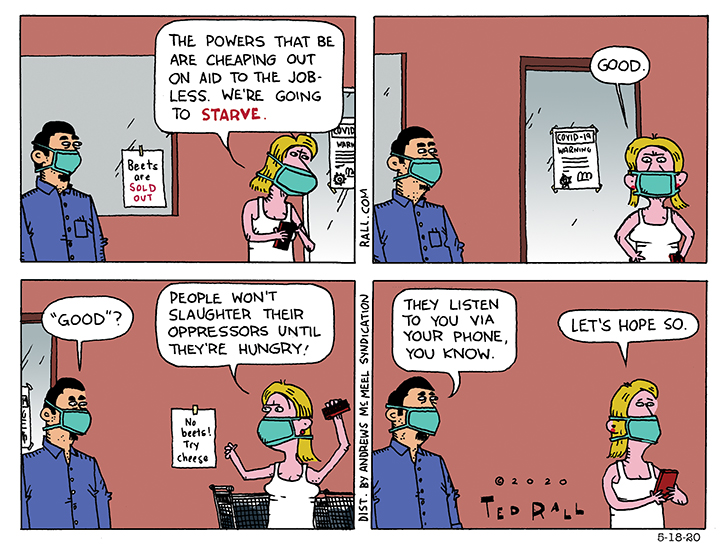

Number one: There’s a reason that other rich countries treat healthcare as a taxpayer-financed social program. Employer-based health insurance was stupid pre-COVID-19 because our economy was already steadily transitioning from traditional full-time W-2 jobs to self-employment, freelance and gig work. The virus has exposed the insanity of this arrangement. Millions of people have been fired over the last two months; now they find themselves uninsured during a global health emergency. The unemployed theoretically face fines for the crime of no longer being able to afford to buy private healthcare.

The second inherent flaw in the U.S. approach is that it’s for profit. Greed creates an inherent incentive against paying for preventative and emergency care. Even people who are desperately ill with chronic conditions see 24% of legitimate claims denied.

When your insurance company issues a denial, they don’t merely pocket that payment. They also add to future profits. Even if you’re insured, the hassle of knowing that you might get hit by a surprise bill for uncovered/out-of-network charges makes you more likely to stay home rather than to risk seeing a doctor or filling a prescription and going broke. “Visits to primary care providers made by adults under the age of 65…dropped by nearly 25% from 2008 to 2016” due to routine denials by insurers, reports NPR.

Denials also create a societal effect: news stories about patients with insurance receiving bills for thousands of dollars after being treated for COVID-19, even just to be tested, prompt people to stay away from hospitals and try to ride out the disease at home. Some of those people die.

There’s another, third structural problem exposed by the pandemic—but it’s not receiving attention from public policy experts or the media. I’m talking about America’s lack of a centralized healthcare system.

A centralized healthcare system has nothing to do with who pays the doctor. A centralized system can be fully socialized, government-subsidized or fully for-profit. In such a scheme all patient records are stored in a central online database accessible to physicians, pharmacists and other caregivers regardless of where you are when you need care. If you fall ill while you’re on a trip away from home, the admitting nurse at a walk-in clinic or hospital has instantaneous access to your complete medical history.

The current system is primitive. Data is not transferable between doctors or medical systems without a patient’s directive, which inexplicably is often required by the obsolete technology of sending a fax. That assumes the sick person is sharp enough to remember which of his previous doctors did what when. And that’s it’s not a weekend or national holiday or a Wednesday, when some doctors like to golf.

Unless a patient happens to be wearing a medical alert bracelet, there is currently no way to determine whether an unconscious victim is allergic to a drug, has a chronic illness or that there’s a treatment regimen proven to be more effective for them. Even if the patient is alert and conscious, a new doctor may ignore her request for a specific medication in favor of cookie-cutter one-size-fits-all treatment.

A few months ago I developed the classic symptoms of what we now know to be COVID-19. I live in New York. I succumbed while on business in LA. Trying in vain to fight off a relentless dry cough, difficulty breathing and day after day of brutal aches and fever, I visited a CVS walk-in clinic. I have a long history of respiratory illnesses: asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, swine flu. I requested a third- or fourth-generation antibiotic since I knew from experience that I would inevitably decline with anything less. “We do not treat viral infections with antibiotics,” the nurse, a charmless Pete Buttigieg type, pompously declaimed. I pointed out that viral lung infections usually have a bacterial component that should be treated with antibiotics.

This would not have been a issue back home in New York, where both my general practitioner and my pulmonologist know my medical history. Either doctor would have prescribed a strong antibiotic and a codeine-based cough syrup.

Because I happened to be in LA, I left CVS empty-handed.

I declined.

It got to the point that I couldn’t walk 100 feet without pausing to catch my breath. I felt like I was going to die.

I called my doctor back in New York. She called in a prescription to the same CVS. It helped arrest my decline. But I wasn’t getting better.

I visited a different walk-in clinic, in West Hollywood. It was a better experience. They tested me for flu (negative), X-rayed me (diagnosis was early stage- pneumonia) and put me on a nebulizer. I began a slow recovery.

A centralized system would have been more efficient. The CVS nurse would have seen my history of non-response to treatment devoid of strong antibiotics. He also might have taken note of my pulmonologist’s effective use of a nebulizer to treat previous bouts of bronchitis and pneumonia. I might have been prescribed the proper medication and treatment as much as a week sooner.

COVID-19 almost certainly would have been detected in the United States sooner if we had a centralized medical system. “One example of a persistent challenge in the early detection of health security threats is the lack of national, web-based databases that link suspected cases of illness with laboratory confirmation. This leaves countries vulnerable, as they cannot accurately and quickly identify the presence of pathogens to minimize the spread of disease,” according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Algorithms can automatically scan massive volumes of information for signs of novel infectious diseases, help identify potential problems and focus responses where they are needed most.

How many people’s lives could have been saved if lockdown procedures had begun earlier? If public health officials had seen the coronavirus coming back in December—or November—they might have been able to protect vulnerable populations and avoid a devastating economic shutdown.

There are substantial privacy considerations. No one wants a hacker to find out that they had an STD or an employer to learn about documented evidence of substance abuse. Keeping a centralized healthcare system secure would have to be a top priority. On the other hand, there is no inherent shame in any kind of illness. In a nightmare scenario in which medical records were to somehow become public, no one would have anything to hide or any reason to look down on anyone else.

We can’t pretend to be a first world country until we join the rest of the world by abolishing corporate for-profit healthcare and decouple insurance benefits from employment. But reform without centralization would be incomplete.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of the biography “Bernie,” updated and expanded for 2020. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)