On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discuss various current geopolitical events, including Biden and Netanyahu’s high-stakes call.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discuss various current geopolitical events, including Biden and Netanyahu’s high-stakes call.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discuss various current geopolitical events, including Biden and Netanyahu’s high-stakes call.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discuss various current geopolitical events, including Biden and Netanyahu’s high-stakes call.

Every country needs a coherent foreign policy. And it’s impossible to overstate the importance of the United States’ military and diplomatic posture.

The U.S. has the world’s second-largest and most sophisticated nuclear arsenal, exclusive comprehensive command over the oceans, perfect strategic geography, has nearly a thousand military bases overseas and is by far the biggest dealer of weapons and ammunition. And it uses them a lot: we have been at war throughout all of our history since independence from Britain.

Backed by this “hard” power, which is used to disrupt and overthrow governments, destroy infrastructure and economies, and generally wreak havoc and mayhem, the U.S. deploys formidable “soft power” via its cultural and linguistic hegemony, which has established English as the world’s lingua franca. It determines whether up-and-coming nations are “permitted” to join the “nuclear club” or whether they can be recognized as sovereign countries. It controls a vast array of intelligence operations (including those purporting to work for other countries) and non-governmental organizations, which pull the strings of foreign-based media outlets. The U.S. even hosts the United Nations.

Our military, economic, cultural and diplomatic power is incalculably formidable—and our reach is infinite.

We have an awesome duty to exercise our massive power responsibly, intelligently, with restraint, and in service of the greater global good; sadly, the opposite has been true more often than not.

When the Left takes over control of the nuclear missile silos, the defense budgets and the embassies circling the globe, everything must change radically.

President Jimmy Carter hinted at what is possible when he promised to prioritize human rights in foreign policy. Though he fell woefully short of his self-professed ideal, propping up brutal dictatorships like the Shah’s torture regime in Iran and arming the far-right anti-Soviet jihadis in Afghanistan, the U.S. did not launch any wars or proxy conflicts during the late 1970s.

First and foremost, the U.S. must adopt a fully defensive military posture. Troops may only be deployed, and then aggressively, in the event of an invasion or armed incursion—or imminent threat thereof, as defined under international law—of U.S. soil.

The U.S. must never enter into any treaty or mutual-defense arrangement under which it might be legally or otherwise obligated to assist or intervene as the result of a conflict to which it is not a party. For example, we should cancel our membership in NATO, a mutual-defense pact whose member states treat an attack on one as an attack on all, Three Musketeers-style. As the lead state that created NATO, we should encourage its dissolution as the type of dangerous interlocking alliances that triggered World War I.

A defense-only defense policy will allow the “defense” budget to shrink to a small fraction of current levels, freeing up trillions of dollars to attend to urgent yet long-neglected domestic needs like fighting poverty and improving our schools. It will eliminate such misbegotten foreign adventurism as the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, covert participation in regime-change “color revolutions,” backing coups such as those that transformed Libya and Honduras into failed states, and the current doomed proxy war against Russia in Ukraine as well as our support of Israel’s war against the Palestinians. Countless lives will be saved and improved as a result. We will acquire fewer enemies, thus reducing the possibility of future terrorist attacks. Here at home as well, we will see fewer hate crimes directed as those who seem to somehow be affiliated or related to whatever nation-state or ethnicity we happen to be designating as our enemy at any given time.

A key part of a comprehensive swords-to-plowshares strategy is to close all of our hundreds of military bases around the planet and bring our troops home where they belong. This will bring an end to the perverse practice of stationing soldiers in a place where they are likely to provoke an attack only to then double- and triple-down on our presence in order to protect the previous force. Smarter not to station them there in the first place.

When a foreign crisis or conflict seems to call for military intervention in order to restore law and order, as may be the case currently in Haiti, to stop genocide as we saw in Rwanda in the 1990s, or for some other benevolent reason free of self-interest, U.S. involvement should be reluctant and carefully considered, and then, should be voted upon directly by the people rather than our elected representatives. Then, should we choose to be involved, any such action must be coordinated by the U.N. in conjunction with a coalition of other member states. The U.S. is neither the world’s policeman nor its mob enforcer; it ought not to pretend otherwise.

As the world’s foremost arms developer, dealer and distributor the U.S. is uniquely positioned to initiate and organize a bold new era of arms control and deescalation. A leftist U.S. will unilaterally point the way forward by methodically dismantling its nuclear stockpile, while encouraging others to do the same. Many countries, like China, Russia and North Korea, spend money they don’t have to build nukes for fear of a U.S. first strike; they would welcome a statement from U.S. that we would never fire nuclear weapons first and that they no longer need to try to keep up with us. We should join the international treaty banning the use of landmines. Similarly, we should forswear the manufacture, deployment and use of unmanned drone weapons, and ask the world to join us in a global convention prohibiting assassination drones.

A Left country prioritizes peace. Thus it is absolutely imperative that a Left-governed United States establish and maintain full and, to the fullest extent possible friendly, diplomatic relations with every other country, no matter what. Because we value and respect each nation’s right to self-determination, it is not the place of the State Department to attempt to pressure or influence the political orientation or style of government of any other country. Whether or not we agree with a foreign state’s ideological, economic, religious or cultural attitudes is irrelevant; a leftist diplomatic corps is always willing to talk to anyone about anything and to remain available to assist U.S. nationals traveling or living in other countries. In keeping with this openminded approach, the United States will end any and all economic and other forms of sanctions against all foreign governments, and promise never to deploy them in the future for any reason whatsoever, no matter how seemingly justified. Sanctions are coercive gangsterism. As the socialist government of Cuba plainly proves, they don’t work anyway. And sanctions only affect ordinary people, never the elites.

The U.S. should never wield trade policy as a cudgel, such as imposing tariffs against imports from one producer but not another. While trade policy should always prioritize the protection of American companies and workers, tariffs and regulations should be applied uniformly to all imported goods without favor or disfavor to one or any group of producers.

To the world, we say: we wish to be your friends. And if we cannot be friends, we will at least do everything in our power not to turn ourselves, as we have done so often in the past, into your enemy.

Next time, what the Left should do about law, order, policing and punishment.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discuss a variety of political topics including Trump leading in swing states.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discuss a variety of political topics including Trump leading in swing states.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discuss various topics around the globe, including the AT&T data leaks.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discuss various topics around the globe, including the AT&T data leaks.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discussed current events from around the globe, including House Speaker Mike Johnson possibly being ousted.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, hosts Angie Wong and Ted Rall discussed current events from around the globe, including House Speaker Mike Johnson possibly being ousted.

The DMZ America Podcast is where civilized but spirited and intelligent political talk thrives. Hosted by editorial cartoonists Scott Stantis (from the Right) and Ted Rall (from the Left), the colleagues and best friends debate the issues of the day.

Robert F. Kennedy’s choice of tech sis and fellow Californian Nicole Stranahan as his vice presidential running mate marks a decidedly unserious turn for a campaign that has already shrunk from 19% to 12% in the polls. Nothing is decided yet, of course, but Ted and Scott doubt that RFK will be able to rescue his presidential bid now.

President Biden keeps arguing that the economy is basically sound and that, sooner rather than later, Americans will start to feel better following that spike in inflation a few years back. The problem is, even if he’s right, how can this president possibly communicate that message, or any message, effectively?

Americans’ national fertility rate is 1.66 children per woman. Now it turns out that sperm counts are plummeting due to environmental causes as well as a nasty disease. Scott and Ted discuss the demographic and cultural implications.

Watch the Video Version: here.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, Angie Wong and Ted Rall delve into various topics domestically and abroad, including Biden’s campaign amid his fundraising efforts.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, Angie Wong and Ted Rall delve into various topics domestically and abroad, including Biden’s campaign amid his fundraising efforts.

The show begins with the hosts discussing Biden’s fundraising success amid his plummeting support with National Director of America First PACT Tom Norton. They also talk about Trump’s attempt to out-fundraise Biden amid his legal expenses.

The show closes with International Relations and Security Analyst Mark Sleboda about Russia’s revelations about the financial link between the Moscow concert hall terrorists and Ukrainian nationalists.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, Angie Wong and Ted Rall discuss various current events, delving into Hunter Biden’s ongoing legal saga.

Jamie Finch: Former Director at the National Transportation Safety Board

Tyler Nixon: Counselor-at-law

Mitch Roschelle: Media commentator

Professor Francis Boyle: Human rights lawyer

In the first hour, Former director of the National Transportation Safety Board Jamie Finch, joins to discuss the aftermath of the Baltimore bridge collapse.

Then, counselor-at-law Tyler Nixon weighs in on Hunter Biden’s bid to get his tax evasion case dismissed.

The show wraps up with Professor Francis Boyle, a human rights lawyer, who gives an analysis of the ongoing negotiations for a ceasefire and the latest out of Gaza.

Learning is a societal and individual good. American businesses, however, have weaponized higher education into an overcredentialization racket that coerces millions of young people to borrow hundreds of billions of dollars in tuition, room and board, often to study subjects in which they have little interest, for the chance to be hired for a job. To add insult to usury, the diploma for which they sink into high-interest student loan debt reflects an education with no useful application to the position where they land.

It is tempting, from the standpoint of the Left, to dismiss the soaring price of college tuition, usurious student loan interest rates and overcredentialization as a first-world problem afflicting middle-class suburbanites who, after struggling after graduation, will soon enough pay off their debt and enjoy a significantly higher income than workers with high-school degrees. But no society can afford to ignore the plight of its most highly-educated ambitious young people who, as Crane Brinton reminded us in “The Anatomy of Revolution,” are an essential catalyst to radical political change. College students are a diverse lot; nearly half are people of color and more than 60% are women. Despite the problems within higher education America has no bigger engine for upward economic mobility.

The problem is, the college income premium only accrues to those who finish all four years and get their degree, which includes very few poor and working-class people. 15% of students from the lowest quartile of wage earners make it all the way through, compared to 61% of those in the top quartile.

Too many employers, too lazy to sort job applicants from a broader pool, demand college diplomas even when the job they are hiring for does not require the relevant education and training, as a way of culling the herd. “More than half of Americans who earned college diplomas find themselves working in jobs that don’t require a bachelor’s degree or utilize the skills acquired in obtaining one,” according to CBS News.

Requiring a superfluous college degree brazenly discriminates against poorer people, expanding and prolonging the class divide. Under a Left government, economic disadvantage would become a protected legal class alongside race, age, sex, gender identity, physical handicap and so on. Workers should be able to report job listings that seek overqualified workers to a federal bureau in the Department of Labor, which would have the power to impose substantial penalties, including fines and compensation for applicants who are discriminated against.

“Nearly two-thirds of American workers do not have a four-year college degree. Screening by college degree hits minorities particularly hard, eliminating 76% of Black adults and 83% of Latino adults,” The New York Times reported in 2022. Yet 44% of all U.S. employers required at least a BA or BS for all their openings.

A 2017 Harvard Business School study found that “60% of employers rejected otherwise qualified candidates in terms of skills or experience simply because they did not have a college diploma.”

Requiring employers to do the right, logical and fair thing, and hire qualified high-school graduates, dropouts and GED holders will allow more Americans to avoid college debt traps, incentivize companies to train workers, give working-class families more opportunities and reduce the high-intensity competition for college and university acceptance.

Student loans are a $1.7 trillion for-profit business which gives lenders the ultimate leverage: no matter what they do or how legitimate their inability to pay, distressed borrowers cannot even discharge their college debts in bankruptcy. At this writing, the average interest rate on student loans is 6.9%. The highest rate at which banks borrow money, however, is 5.5%—and the rate for the much longer terms of student loans is lower.

Young scholars are bright, vulnerable citizens with endless potential, not a profit center for transnational lending institutions. If we must have a for-profit system of post-secondary education and student loans to afford it, those loans should be at zero profit to banks or anyone else. And they should be able to be discharged in bankruptcy, just like any other debt.

Because college dropouts do not enjoy the college wage premium, their loans should be forgiven entirely or heavily discounted.

But the duty of leftists is no merely to tinker at the edges to make a troubled system fairer or more efficient. We look at a situation and ask: do we need a complete overhaul? If we were inventing America’s higher education system from scratch, is what we have now anything close to what we would come up with?

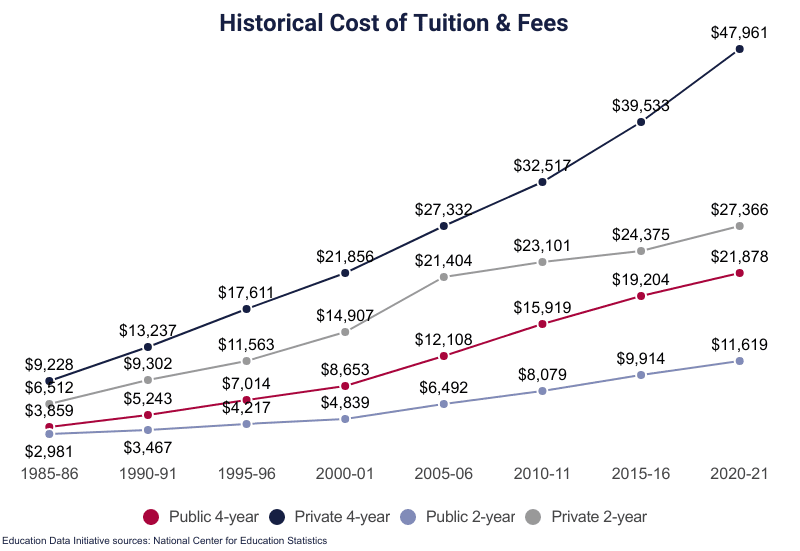

It’s hard to imagine that anyone, regardless of their general political orientation, would say that we have the best possible way to educate young people and prepare them for the future of work and life in general. The average household with student loan debt owes $55,000. Over a 10-year term at 6.9%, the total due including interest is $76,000. That’s the cost of a starter home in many parts of the country, and much more than students and their families spend in virtually any other nation.

Thirty-nine nations, including European powerhouses like France and Germany but also poor ones like Greece and Portugal, as well as developing socialist countries like Cuba and Brazil, currently offer their citizens college for free or for nominal fees.

We can too.

Students and parents borrowed $95 billion in the 2021-22 academic year. Going forward, then, replacing every penny borrowed as student loans as a free federal grant would cost the government about $100 billion—a tiny portion of the $4.5 trillion a year we’re currently wasting on the military and other misbegotten budgetary priorities.

There is also an argument for nationalizing public and/or private institutions of higher education. A college education, after all, will remain essential for a significant segment of the population even if we abolish employers’ current obsession with overcredentialization. Goods and services that are essential for contemporary human existence are, by definition, too important to be left to the fickle whims of a boom-and-bust marketplace. A college education surely qualifies. Higher education is too expensive a cost for cities and states to absorb. For the feds, however, it’s not that big a deal. Moving to federal control would create economies of scale and countless efficiencies, such as the ability to negotiate discounted prices for textbooks and equipment, plus the ability to transfer professors and personnel throughout the system in accordance with educators’ desires and regional needs.

Next: What should a Left foreign policy look like?

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

On this episode of The Final Countdown, the focus was on recent developments surrounding NBC’s internal turmoil and other significant global events.

On this episode of The Final Countdown, the focus was on recent developments surrounding NBC’s internal turmoil and other significant global events.

Steve Gill: Lawyer and Political Commentator

Dan Lazare: Independent Journalist

Mark Sleboda: International Relations and Security Analyst

Dan Kovalik: International Human Rights and Labor Attorney

In the first hour, Steve Gill discussed the Baltimore bridge collapse and the outdated U.S. infrastructure.

Then, Dan Lazare joined later to share his insights into RFK Jr.’s announcement of his running mate, Nicole Shanahan.

In the second hour, international relations analyst Mark Sleboda delved into the Russian intelligence chief’s accusations against the U.S., Ukraine, and UK regarding the Moscow concert hall massacre.

The show closes with human rights attorney Dan Kovalik addressing the rift between Biden and Netanyahu over a ceasefire resolution passing in the UN Security Council.