On Economy, Pessimism Abounds

Twenty years ago, in 1990, the American economy was in the third year of a deep recession. It was impossible to find a job. The 1980s housing bubble had popped; high-end housing prices in New York City dropped by 80 percent. Then, as now, the president seemed oblivious, aloof and clueless. Two years later, with no recovery in sight, angry voters turned him out of office.

But help was on the way. Something called the World Wide Web appeared in 1991. Two years later, Mosaic—the first graphic web browser, which would evolve into Netscape—was introduced. The Internet boom began. It flamed out seven years later, but in the meantime tens of millions of Americans collected new, higher paychecks. They spent their windfall. Consumer spending exploded. So did government tax revenues. When Bill Clinton left office in 2001, the Office of Management and Budget was projecting a $5 trillion surplus over the next ten years—enough to pay off the national debt and fund Social Security for decades. Unemployment had fallen to four percent. United States GDP accounted for a quarter of the global economy.

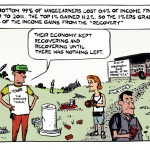

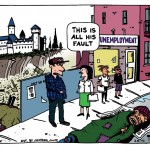

It’s different this time. We are in a deep depression: calculated the same way as it was in the 1930s, the unemployment rate is the same as it was in 1934. Global credit markets have stalled. Investment has ceased.

And help isn’t coming.

Despair oozes between the lines of media interviews of economists. Asked where the recovery will come from, they run down the list of theoretical possibilities, dismissing them one by one. The question remains unanswered. Which is, of course, the answer.

No one knows where the recovery will come from for a simple reason: It isn’t coming. Not any time soon.

“A robust rebound in retail sales earlier in the spring had fueled hopes that consumer spending—which makes up about 70% of U.S. economic activity—would give a strong lift to the recovery. But now that is looking increasingly unlikely,” reported The Los Angeles Times. “Households are not going to be the engine of growth for some time,” Paul Dales of Capital Economics told the newspaper.

“In past recoveries, booming construction activity led the way, fueling spending and other economic activity. That’s not happening this time,” said the Times.

If there’s some new technological innovation—like the Internet in the early 1990s—waiting in the wings, no one has heard or seen it.

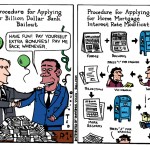

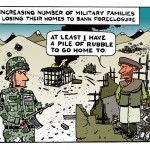

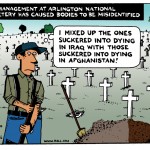

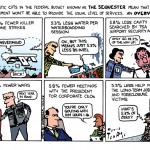

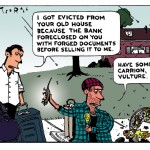

Forget about Congress. The feds wasted hundreds of billions of dollars to bail out banks, insurance companies and big automakers who used our taxpayer money to give raises to their top executives and remodel their offices. Meanwhile, the stimulus that needed to happen—bailing out distressed homeowners, small businesses and individuals who lost their jobs—never happened. Now Congress is worried about the deficit. So read my lips: no new bailouts, not even one that might actually work.

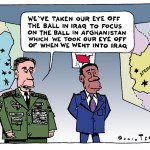

Some think the U.S. could export its way out of the depression. But a radical restructuring of trade agreements and manufacturing infrastructure would have to come first, followed by years of expansion. U.S. policymakers haven’t even begun to think about the first move. Moreover, the rest of the world isn’t in a position to buy our stuff. The rate of expansion of the economies of China and Japan is slowing down. Germany and other EU nations are imposing austerity measures.

Globalization is key. Writing in The Wall Street Journal, John H. Makin argues that the actions of individual G20 nations threaten to bring the whole system crashing down in a Keynesian “paradox of thrift.”

Makin says: “Because all governments are simultaneously tightening fiscal policy, growth is cut so much that revenues collapse and budget deficits actually rise. The underlying hope or expectation that easier money, a weaker currency, and higher exports can somehow compensate for the negative impact on growth from rapid, global fiscal consolidation cannot be realized everywhere at once. The combination of tighter fiscal policy, easy money, and a weaker currency, which can work for a small open economy, cannot work for the global economy.”

Adds Mike Whitney of Eurasia Review: “Obama intends to double exports within the next decade. Every other nation has the exact same plan. They’d rather weaken their own currencies and starve workers than raise salaries and fund government work programs. Class warfare takes precedent over productivity, a healthy economy or even national solvency. Contempt for workers is the religion of elites.”

One can hardly blame workers for fighting back. Two weeks after hundreds of protesters rioted at the G20 summit meeting, Toronto police are pouring through thousands of photos and are using facial recognition software to track down offenders. They have even released a Top 10 “Most Wanted” list and related pictures of activists.

Whether or not the anti-globalization protesters are motivated by the struggle for liberation and economic equality, they symbolize the industrialized world’s best chance to prevent the economy from continuing its current process of slow-motion collapse. If the system cannot be saved by consumers, business or government, the system itself must be revamped and replaced. Late-period global capitalism’s constant cycle of booms and busts is unsustainable and intolerable. States must regulate and equalize incomes, and control production.

If the cops were smart, they would track down and arrest those people who really are ruining the economy. They could start by listing and releasing the photos of the attendees of the G20.

(Ted Rall is the author of “The Anti-American Manifesto,” to be published in September by Seven Stories Press. His website is tedrall.com.)

COPYRIGHT 2010 TED RALL