US citizenship officially means NOTHING. State Dept annulled Snowden’s passport – though he hasn’t been found guilty http://ow.ly/mjcrL

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Get Pissed Off and Break Things

Why Are Americans So Passive?

There’s a reason “Keep Calm and Carry On” is everywhere. When people lose everything — their economic aspirations, their freedom, their privacy — when there’s nothing they can do to restore what they’ve lost — all they have left is dignity.

Remember Saddam? Seconds before he was hanged, disheveled and disrespected, the deposed dictator held his head high, his eyes blazing with contempt as he spat sarcastic insults at his executioners. He “faced death like a lion,” said his supposed body double, Latif Yahia, and no one could argue. He left this life with the one thing he could control intact.

Dignity. That’s what “Keep Calm and Carry On” is all about. That’s what we think of when we think of the Battle of Britain. As German bombs rained down, the English went about their business. Like the iconic photo of the milkman tiptoeing over rubble. Like the bomb-damaged stores whose shopkeepers posted signs that read “We are still open — more open than usual.”

Man, that is so not us.

You’ve seen the T-shirts, with their clean Gill Sans-esque lettering and iconic crown. There are mugs, postcards and posters. Of course. It’s a reproduction of a propaganda poster from World War II, an (unsuccessful, because it wasn’t distributed) attempt by the British government to steel jittery citizens during the Blitz.

“Keep Calm and Carry On” merch dates to 2000 but really took off after 9/11; the popularity of the image, the stoicism of its call to stiffen upper lips everywhere, and numerous parodies (“Stay Alive and Kill Zombies”) has generated millions of dollars of profits, inevitably sparking lawsuits and inspiring a song by John Nolan.

Why is a meme originally prepared for a possible German invasion of the UK (which is why it wasn’t released) popular now? Zizi Papacharissi, communications professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, points to the crappy economy. “We are undergoing a profound and fairly global economic crisis, so it is natural to revisit the saying: Keep calm and carry on. It reminds us of courage shown back then, and how courage shown helped people pluck through a crisis.”

It’s also a reaction to terrorism — or more accurately a reaction to the initial reaction to the 9/11 terrorist attacks: hysteria, jingoism, multiple wars of choice, all doomed. More than any other factor, Obama owed his 2008 victory to his (Maureen Dowd called him) Vulcan personality: cool, implacable, possibly non-sentient, the anti-Dubya.

What wouldn’t we give for a 2001 do-over? No invasions, no Patriot Act, no Gitmo, no “extraordinary renditions,” no New York Times op-ed pieces arguing in favor of “enhanced interrogation techniques.” Treat 9/11 like a crime, let the FBI go after the perps. Reach out to Muslims, reconsider our carte blanche to Israel, and most of all: go slow. Don’t freak out.

Perspective: 3,000 deaths is awful. 9/11 was shocking. We killed 2 million Vietnamese people, yet they’re going strong. With a minimum of whining.

And yet…

Sometimes you need some perspective to your perspective.

There are times when it’s appropriate to freak out. When, in fact, it’s downright weird and unhealthy and wrong not to flip your lid. For example, when you get diagnosed with a terrible disease. When someone you love dies.

There are also times when big-picture, impersonal stuff, including politics and the economy, ought to make you crazy with rage or grief or…something. Not nothing. Not just keeping calm and carrying on.

Keeping calm and carrying on was an appropriate response to the Blitz. Short of moving away from the targeted area, there’s nothing you can do about bombs. Living or dying is a matter of happenstance. Keeping calm might help you make smart decisions. Panic is usually more dangerous than self-control.

The same is true of terrorism. Terrorists will kill you, or not — probably not. You can’t fix your fate.

But that is decidedly not true about the economy. Not when what is wrong with the economy is not something no one can control — a giant meteor, bad weather, panic in the markets — but something that most assuredly can and indeed should be, like the systemic transfer of wealth from the poor and middle-class to the rich that has characterized the class divide in Western nations since the 1970s. The appropriate, intelligent and self-preserving response to mass theft is rage, demands for action, and decisive punishment of political and economic leaders who refuse to change things.

As one revelation about the National Security Agency’s spying follows another, the “Keep Calm and Carry On” meme seems less like an appeal to dignity and calm reserve than the much older, classic response of the power elite to their oppressed subjects: Shut the Fuck Up.

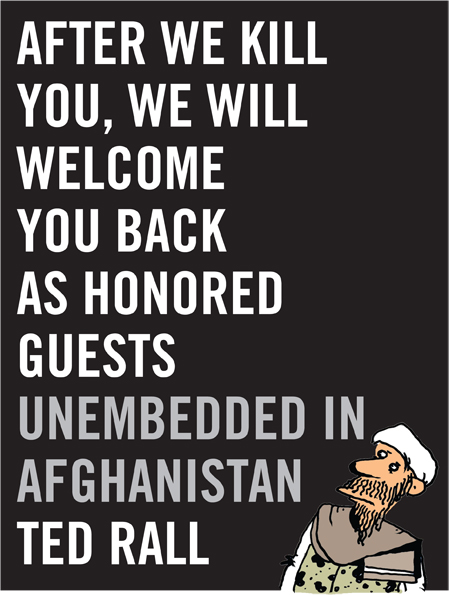

(Ted Rall’s website is tedrall.com. His book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan” will be released in March 2014 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

COPYRIGHT 2013 TED RALL

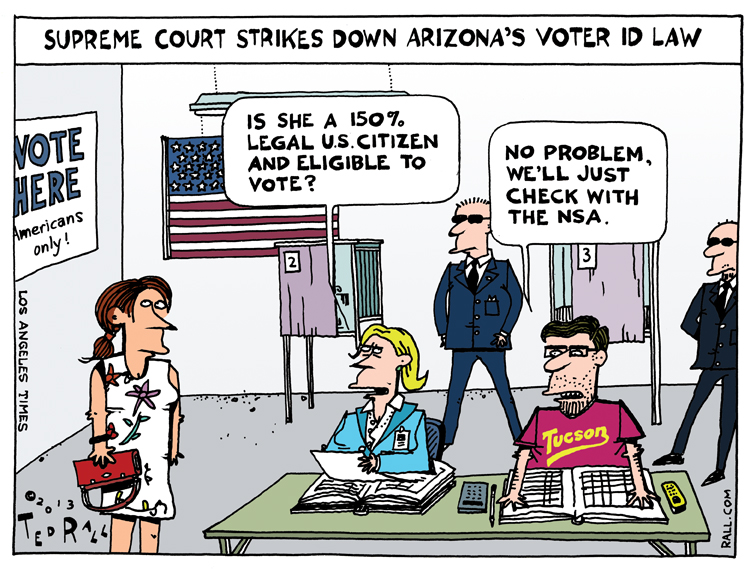

Voter ID Law Struck Down

I draw cartoons for The Los Angeles Times about issues related to California and the Southland (metro Los Angeles).

This week: The US Supreme Court has stricken down Arizona’s Voter ID law. Fortunately, there are other ways to get information about people.

NPR Smears Food Stamp Program

NPR News at 7 am: w/o context, it says cost of food stamp program has doubled since 2008. But that’s because more Americans are poor, not due to government waste. Another way they contribute to the right-wing agenda.

Obsessed with PRISM

I admit it: I’m obsessed with the NSA’s recently revealed PRISM program. Is it just me? I’m still thinking about and commenting on this, but I wonder if this is like torture and drones — just another scandal no one really cares about but the victims.

After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back as Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan

It’s official: my long-awaited book comes out March 25th.

You can pre-order it here.

Here’s the cover:

Are There 10,000 Potential Terrorists on Facebook?

That’s how many requests Facebook for customer data Facebook says it got from the NSA.

Could there really be 10,000 potential terrorists on Facebook? If so, maybe the the solution is to shut down that nest of vipers.

Seriously, sounds like Obama’s NSA is interested in stuff other than terrorism. Occupy movement, anyone?

LinkedIn Cuts Out Writers

For content providers, the Internet is usually a good news – bad news story. It initially sounds like good news; once you dig a little deeper, you learn about the rotten underbelly. And so it goes with today’s New York Times article about LinkedIn and the fact that they are offering original content by the rich and famous.

For free.

LinkedIn is offering original content by content providers, in the form of essays about how to improve your career prospects among other things.

Read down a little bit and you quickly learn that the rich and famous people who have been asked to contribute are not being compensated. Which makes you ask: how did they get these people to do it? Well, the truth is they aren’t.

People like President Clinton don’t write their own opinion columns, they’re ghostwritten by interns. Personally, I don’t think that this should be permitted. If someone’s byline appears under an article, it seems to me to be a basic predicate of journalistic ethics that that piece should be offered by the person it purports to be authored by.

So why do they do it? Or more accurately, why do their interns do it? For the free publicity. For politicians and other people who make their living by selling influence – and speeches and books – it makes sense to promote yourself anyway you can. It doesn’t matter that they don’t get paid.

The problem is, this practice leads to a lot of crappy content by people looking to promote themselves and it drives down the prices for those of us you were actually trying to learn a living as writers. It’s ugly, it’s nasty, and I don’t know when it’s going to come to an end.

New (true) Graphic Novel by David Axe

Check it out! My friend and fellow Afghan war correspondent David Axe has a new graphic novel at Medium.com.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: 10 Things You Don’t Know About How the NSA Spies on You

The Least Most Untruthful Analysis of Obama’s Orwellian Dystopia

Glenn Greenwald of The Guardian says “a lot more significant revelations” about America’s colossal Orwellian surveillance state are coming down the pike — courtesy of the thousands of pages of classified documents he obtained from Edward Snowden, the heroic former CIA contractor. That should be fun.

In the meantime, we’ve got a pair of doozies to digest: Verizon’s decision to turn over its the “metadata” — everything about every phone call (except the sound) to the NSA, and the PRISM program, under which the biggest Internet companies (Google, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, etc., pretty much all the top outfits except Twitter) let the NSA read our emails, see our photos, even watch our Skype chats.

Establishment politicians and their media mouthpieces are spinning faster than a server at the NSA’s new five zettabyte data farm in Utah, doing everything they can to obfuscate in the hope that we’ll forget this whole thing and climb back into our pods in The Matrix.

So let’s get some clarity on what’s really going on with 10 things you probably don’t know about the NSA scandals.

1. PRISM, not Verizon, is the bigger story.

Government-aligned mainstream media outlets like The New York Times and NPR focus more on Verizon because — though what the phone company did was egregious — it’s less indefensible. “Nobody is listening to your telephone calls,” Obama says. (When that’s what passes for reassurance, you’ve got a PR problem.) PRISM, they keep saying, is targeted at “foreigners” so Americans shouldn’t be angry about it. But…

2. PRISM really is directed at Americans.

“Unlike the call data collection program, this program focuses on mining the content of online communication, not just the metadata about them, and is potentially a much greater privacy intrusion,” notes Popular Mechanics.

Director of National Intelligence James Clapper testified to Congress that the NSA does not collect “any type of data at all on millions or hundreds of millions of Americans.” “Not wittingly.” As The New York Times said in an uncharacteristically bold post, this is a lie. Here’s what’s behind the Rumsfeldian logic of what Clapper describes as his “least most untruthful” testimony: “What I was thinking of,” explains Clapper, “is looking at the Dewey Decimal numbers of those books in the metaphorical library. To me the collection of U.S. persons’ data would mean taking the books off the shelf, opening it up and reading it.”

In other words, the NSA collects the search histories, emails, file transfer records and actual live chats of every American. They store them in a data farm. Whenever the NSA wants to look at them, they can. But according to Clapper, this isn’t “collecting.” It’s only “collecting” when they choose to read what they have.

I have bought several books. They’re on my shelf. I haven’t read them yet. Have I “collected” them? Of course.

I don’t want the NSA to read my sexts or look at my dirty pictures. The fact that they may not have gotten around to it yet — but have them sitting on their shelves — doesn’t make me feel better.

3. President Obama should be impeached over this.

Richard Nixon was. Or would have been, if he hadn’t resigned. Obama, his top officials and his political surrogates have repeatedly and knowingly lied to us when they said the NSA didn’t “routinely sweep up information about millions of Americans.” He should go now. So should others who knew about this.

4. PRISM and other NSA spy programs are not approved by courts or by Congress.

White House defenders say the surveillance — which is, remember, a comprehensive vacuuming up of the entire Internet, and of every phone call ever made — has been approved by the legislative and judicial branches, so there’s nothing to worry about. But that isn’t true. The “FISA court” is so secret that, until last week, no one had ever seen a document issued by it. It’s not a real court. It’s a useless rubber stamp panel that literally approves every surveillance request the government asks for. In 2012, that’s 1856 requests and 1856 approvals.

Very few members of Congress were aware of the Verizon or PRISM programs before reading about them in the media. Members of the Senate Intelligence Committee, a few select Friends of Barack, that’s it. That’s not Congressional oversight. Real oversight occurs in full session, in public, on C-SPAN.

5. There is no evidence that NSA spying keeps America safe. And so what if it did?

According to government officials, PRISM saved the New York City subways from being bombed in 2009. Actually, the alleged would-be terrorist was caught by old-fashioned detective work, not data-mining. There is zero evidence that the NSA has saved a single American from being blown up.

But so what if it did? In recent years, between 15 and 17 Americans a year died worldwide from terrorist attacks. You’re as likely to be crushed to death by your television set. It’s sad for the dozen and a half victims, of course. But terrorism is a low, low national priority. Or it should be. Terrorism isn’t enough of a danger to justify taking away the privacy rights of 320 million people.

6. This is not a post-9/11 thing.

We’re being told that PRISM and the latest Patriot Act-approved surveillance state excesses date back to post-9/11 “make us safe at any cost” paranoia. In fact, the NSA has been way up in your business long before that.

Back in December 1998 the French newsweekly Le Nouvel Observateur revealed the existence of a covert partnership between the NSA and 26 U.S. allies. “The power of the network, codenamed ECHELON, is astounding,” the BBC reported in 1999. “Every international telephone call, fax, e-mail, or radio transmission can be listened to by powerful computers capable of voice recognition. They home in on a long list of key words, or patterns of messages. They are looking for evidence of international crime, like terrorism…the system is so widespread all sorts of private communications, often of a sensitive commercial nature, are hoovered up and analyzed.” ECHELON dates back to the 1980s. PRISM picks up where ECHELON left off, adding the Internet to its bag of tricks.

7. Edward Snowden expects to be extradited.

U.S. state media wonders aloud, “puzzled” at whistleblower Snowden’s decision to go to Hong Kong, which routinely extradites criminal suspects to the United States. But Snowden’s explanation is crystal clear. All you have to do is listen. “People who think I made a mistake in picking HK as a location misunderstand my intentions,” he told a local newspaper. “I am not here to hide from justice; I am here to reveal criminality.” Snowden could go to Ecuador, or perhaps Venezuela or Iceland. He’s staying put because he wants to face trial in the U.S. And I doubt he’ll cop a plea when he does. He wants a political hearing so he can put the system on trial. In the meantime, he’ll use the time it’ll take Obama’s legal goons to process the extradition to talk to journalists. To explain himself. To make his case to the public. And, of course, to help shepherd those new revelations Greenwald mentioned.

8. Caught being evil — or collaborating with evil — Google and other tech companies are scared shitless.

And they should be. Consumers and businesses know now that when Big Brother comes calling, Big Tech doesn’t do what they should do — protect their customers’ privacy by calling their lawyers and fighting back. This could hurt their bottom lines. “Other countries will start routing around the U.S. information economy by developing, or even mandating, their own competing services,” speculates Popular Mechanics. Europe, worried about the U.S. exploiting the NSA for industrial espionage, began working on work-around systems that avoid U.S. Internet concerns.

9. 56% of Americans trust the government’s PRISM program, which the government repeatedly lied about. What people don’t know should worry them.

You’re not a terrorist. You don’t hang out with them. So why worry? Because the data collected by the NSA isn’t likely to stay locked up in Utah forever. Data wants to be free — and hackers have already proven they can access the NSA. Some want to sell it to private concerns. To insurance companies, so they can determine whether your buying habits make you a suitable risk. To banks. To security outfits, to run background checks for their clients. To marketers. Mining of Big Data can screw up your life — bad credit, can’t get a job — and you’ll never know what you hit you. Oh, and don’t forget: governments change. Nixon abused the IRS and FBI to attack political opponents. Innocuous census data that collected religious affiliations was used by the Nazis to round up Jews when they came to power.

10. In the long run, the end of privacy will liberate us.

Everyone (who isn’t boring) has a dirty secret. The way things are going, all those secrets will be as out as Dan Savage — and just as happy and self-assured. Blackmail — the nobody-talks-about-real-reason-PRISM-is-creepy — only works if most dirty secrets are hard to come by. But if everyone’s got a nude photo online, if everyone’s sexual deviations are searchable and indexed, the power of shame goes away as quickly as it does at a nudist colony. By the time the surveillance state plays out, we may look back at 2013 as the year when America began to move past Puritanism.

If we’re not in a gulag.

(Ted Rall’s website is tedrall.com. His book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan” will be released in 2014 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

COPYRIGHT 2013 TED RALL