Originally published by ANewDomain.net:

Donald Trump is under fire and losing business for racist remarks about Mexican people. But do the presidential candidate’s words and insults matter more than lives? U.S. President Barack Obama is responsible for the murders of innocent people every day, and no one seems to care about that. Strange but true.

But Germany destroyed massive amounts of infrastructure during World War II — and looted the nation’s Treasury. The Greek government estimates that Germany owes it 279 billion euros for the damage.

But Germany destroyed massive amounts of infrastructure during World War II — and looted the nation’s Treasury. The Greek government estimates that Germany owes it 279 billion euros for the damage.

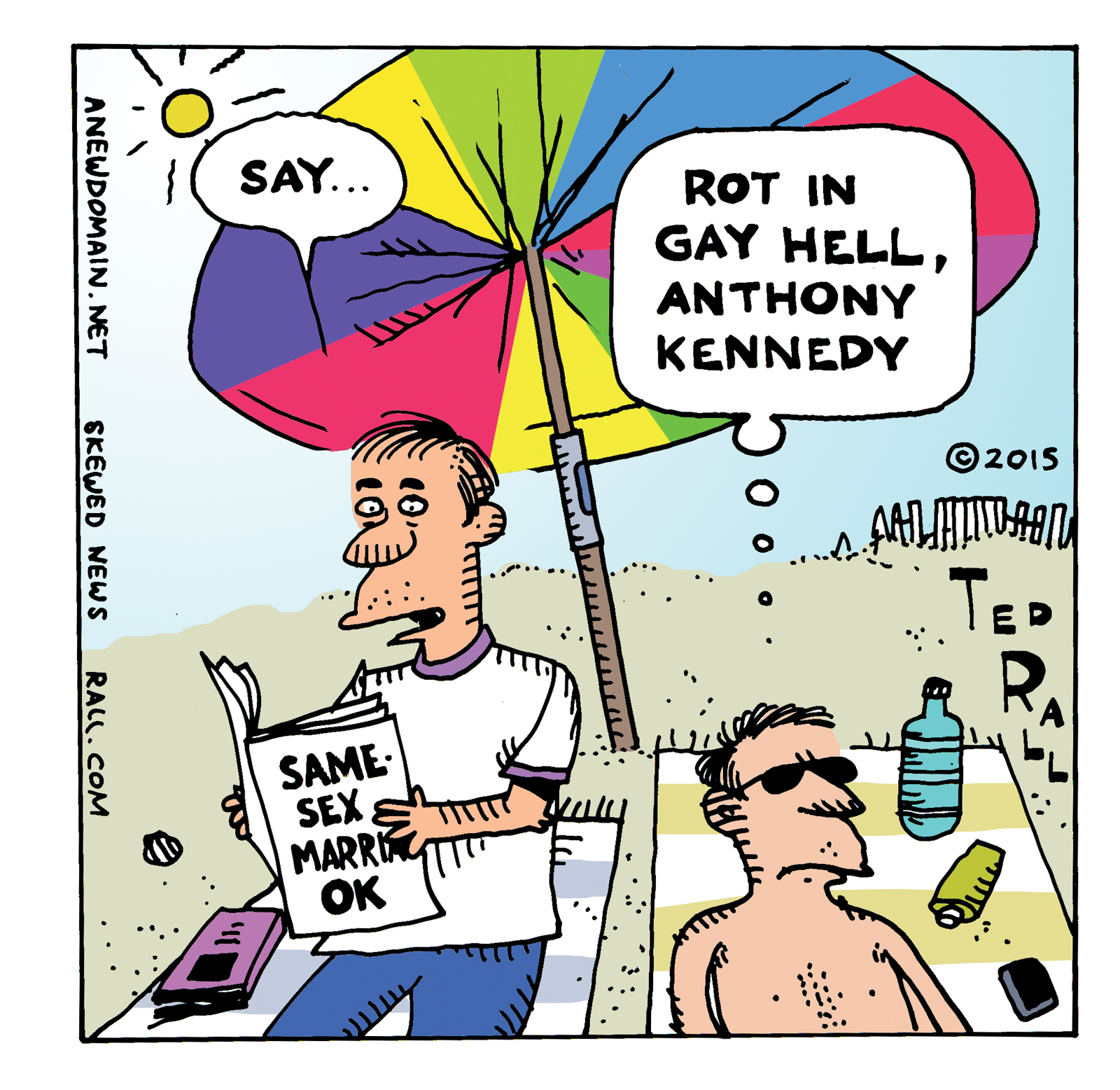

I thought of this famous quote on Friday when I heard that the United States Supreme Court had overturned laws against same-sex marriage in every state.

I thought of this famous quote on Friday when I heard that the United States Supreme Court had overturned laws against same-sex marriage in every state. That is when philosophers and politicians agreed that there were certain inalienable, inherent rights.

That is when philosophers and politicians agreed that there were certain inalienable, inherent rights.  Again, it can and it did. But I think Huckabee and Jindal are wrong — not only on the legal side of the argument, but on the religious one, too.

Again, it can and it did. But I think Huckabee and Jindal are wrong — not only on the legal side of the argument, but on the religious one, too. There is, and there never was, any good reason to prohibit same-sex marriage. When the idea first came up, in the 1980s and 1990s in the United States, I remember asking myself two questions.

There is, and there never was, any good reason to prohibit same-sex marriage. When the idea first came up, in the 1980s and 1990s in the United States, I remember asking myself two questions.  The answer to that question is: It can’t. It doesn’t. Most people realize that. That’s why this debate has moved so quickly.

The answer to that question is: It can’t. It doesn’t. Most people realize that. That’s why this debate has moved so quickly. t their lovers as adults and calling them “nephews” or some other far-fetched relation just to get these basic rights.

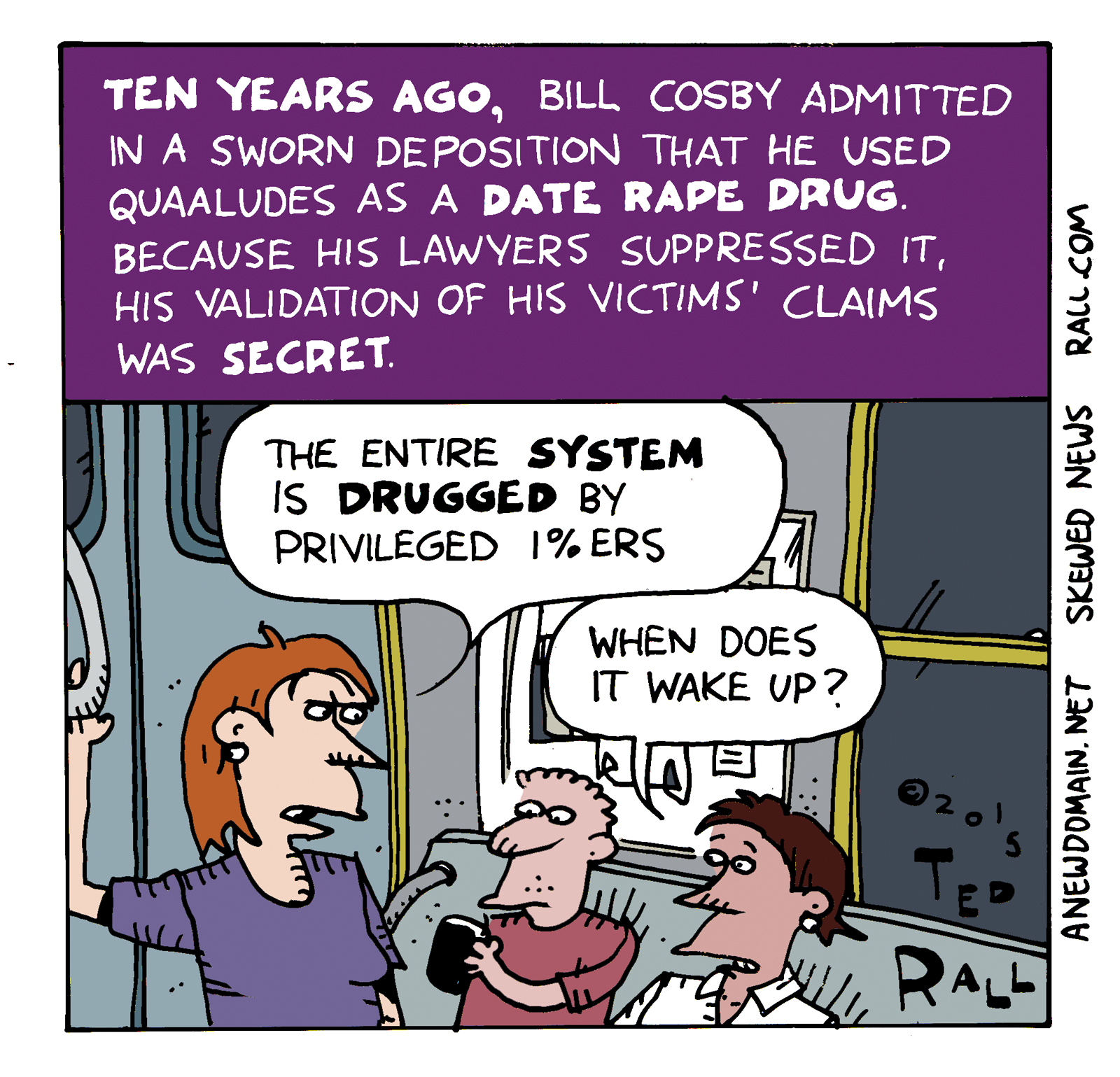

t their lovers as adults and calling them “nephews” or some other far-fetched relation just to get these basic rights. Because Republicans, and many Democrats, including Bill and Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, wouldn’t budge on civil unions, a more radicalized legal process was initiated.

Because Republicans, and many Democrats, including Bill and Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, wouldn’t budge on civil unions, a more radicalized legal process was initiated.

Never mind flying cars.

Never mind flying cars.

Dorsey is currently running Twitter as interim head, and has made no progress yet on the shockingly difficult puzzle of how to monetize billions of brainfarts under 140 characters.

Dorsey is currently running Twitter as interim head, and has made no progress yet on the shockingly difficult puzzle of how to monetize billions of brainfarts under 140 characters.

“Not a fan of the beard,” Dorsey’s mom Marcia tweeted.

“Not a fan of the beard,” Dorsey’s mom Marcia tweeted. Neither have the fabled

Neither have the fabled