One of my complaints about mainstream media is that they recruit reporters from inside the establishment—Ivy League colleges, expensive graduate journalism programs, rival outlets with similar hiring practices. Some staffs develop admirable levels of gender and racial diversity. But they all come from the same elite class. Rich kids believe in the system and they accept its basic assumptions.

On New Year’s Day a reporter (UPenn and Oxford, of course) published a solid piece for The Washington Post about an important issue, how America’s “fractured healthcare system” hurts our response to COVID-19. Seeking to answer the question of why the pandemic is still going on after the miraculously rapid development and distribution of vaccines, the Post identified organizational shortcomings as part of the problem, citing the need for “improvements on the delivery side.” She quoted an expert who called for “increasing staffing and funding for local health departments, many of which have been running on a shoestring. Officials in some local health departments still transfer data by fax.” Both true. I’ve been asked to fax my records recently.

But.

Nowhere in the Post piece was there any mention of what the United States is missing that most other countries in the world are not: a unified national healthcare system like the United Kingdom’s NHS.

I’m not talking here about fully-socialized medicine or a single-payer Medicare For All system like the one championed by Bernie Sanders, although I strongly believe Americans need and deserve one. This isn’t about who pays for healthcare (though it should obviously be covered 100% by the government).

It’s about data integration.

In the same way that law-enforcement agencies across the country can access criminal records from other jurisdictions via the FBI’s National Data Exchange system, public-health officials need access to a real-time, constantly-updated source of every report of disease whether it’s known or novel, the visit was paid for in cash by the patient or covered by insurance, or it was diagnosed by a country doctor, walk-in urgent-care center or a giant urban hospital system.

A fully-integrated national healthcare database would be a powerful side benefit of a national healthcare system like Medicare For All. But how likely is Bernie Sanders’ pet project to cross the mind of a writer who graduated from UPenn and Oxford and has a gold health insurance plan provided by her employer, who is Jeff Bezos?

Here in America, the nation’s top epidemiologists at the Centers for Disease Control are flying blind, relying on algorithmic models that estimate what’s going on rather than providing accurate, precise situational awareness.

I tested positive for COVID-19 on December 30. I notified my doctor’s office on January 1 but due to the holiday didn’t hear back until January 3. Will New York City authorities and/or the CDC be notified about my case and, if so, when?

Several friends and friends of friends also tested positive during the Omicron surge using home tests. Many, probably most, didn’t tell their doctor. You have to assume that official numbers for Omicron have been significantly underreported.

If we had a national healthcare system instead of a medical Wild West in which the ailing are jostling against each other fighting over $24 testing kits like shoppers rushing into Best Buy on Black Friday, testing would be handled through clinics and doctor’s offices in coordination with the federal government—which would instantly compile the results.

A national healthcare database could include “visualization tools to graphically depict associations between people, places, things, and events either on a link-analysis chart or on a map. For ongoing investigations, the subscription and notification feature automatically notifies analysts if other users are searching for the same criteria or if a new record concerning their investigation is added to the system… [allowing] analysts to work with other analysts across the nation in a collaborative environment that instantly and securely shares pertinent information.”

I lifted that last quote from an FBI description of their police database. Crime, by the way, kills a small fraction of the number of Americans who die from disease.

HIPAA regulations governing patient records would need to be modified by Congress, but consider the potentially lifesaving benefits even when there is no longer a pandemic. Medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States.

Decentralized recordkeeping is a public-health disaster. If you live in Wyoming, there is no good reason that your healthcare records shouldn’t be accessible to first responders driving the ambulance that responds to a call that you collapsed and are unconscious at a mall in Florida. As soon as you are identified—something that could be facilitated by a national healthcare ID card that you carry in your wallet or as an app on your smartphone—EMS workers could use your patient history to identify chronic problems. They could avoid a medication to which you might be allergic or feel confident in administering one thanks to the knowledge that you are not.

I didn’t go to UPenn and Oxford. As an independent writer, I pay my own health insurance. I am reminded of America’s crappy healthcare system every time I pay my ACA bill and every time I cough up a co-pay. Newspapers like the Post may or may not need me. But they definitely need people like me if they want to relate to the readers they’re trying to serve.

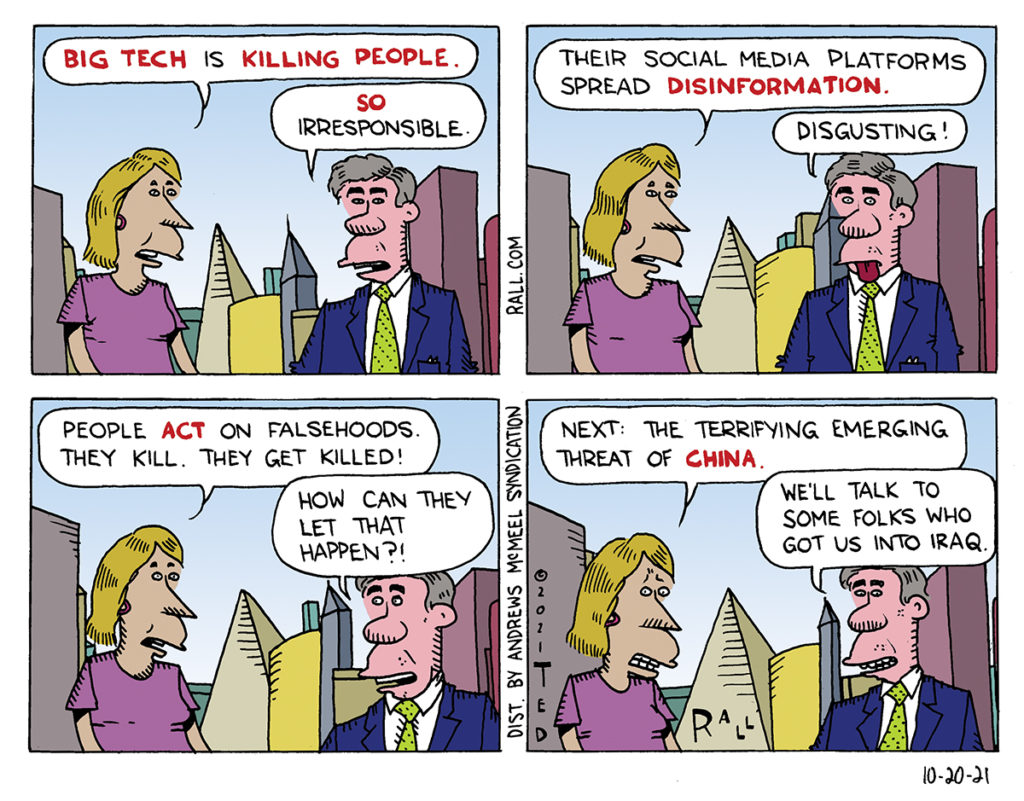

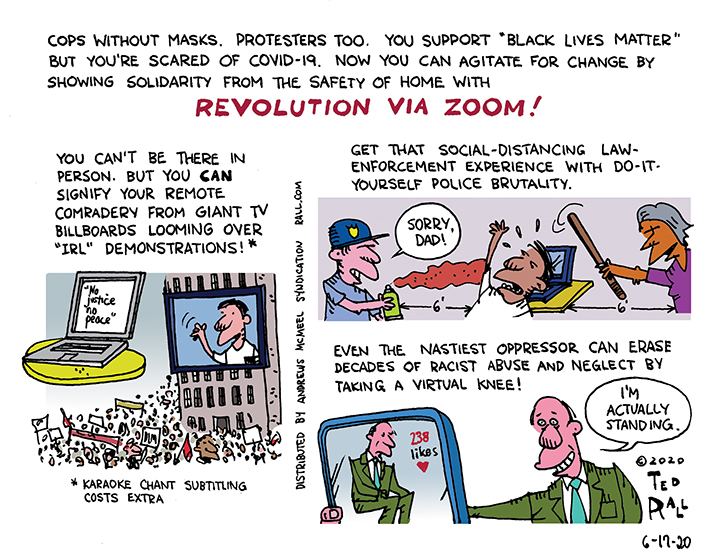

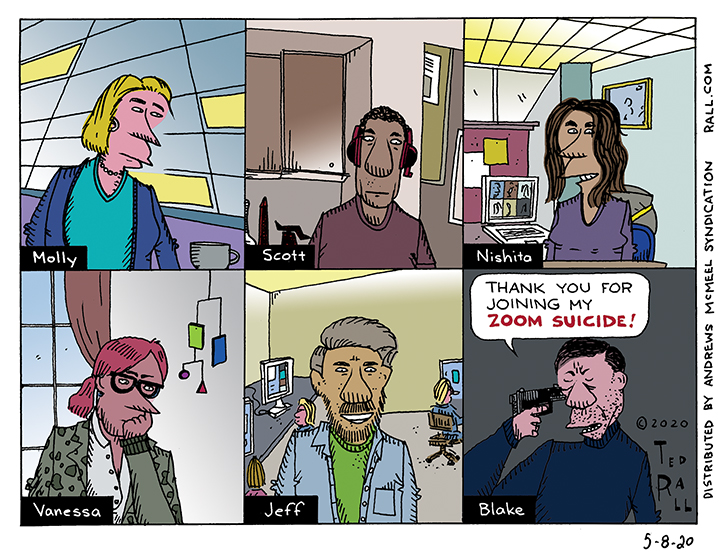

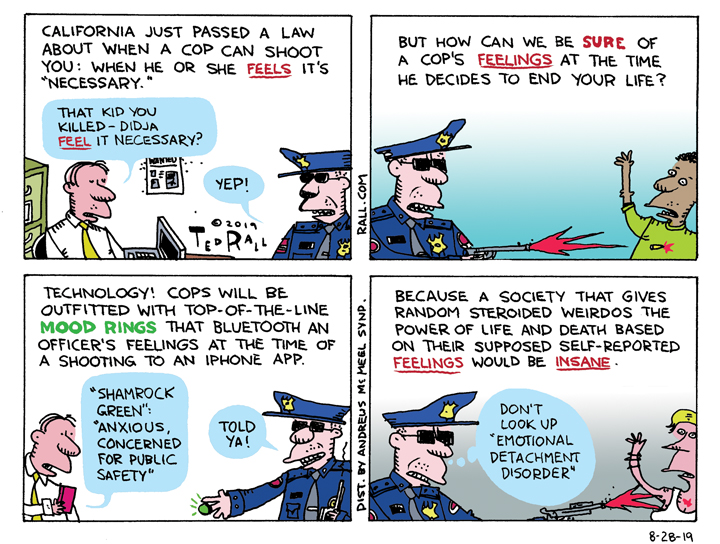

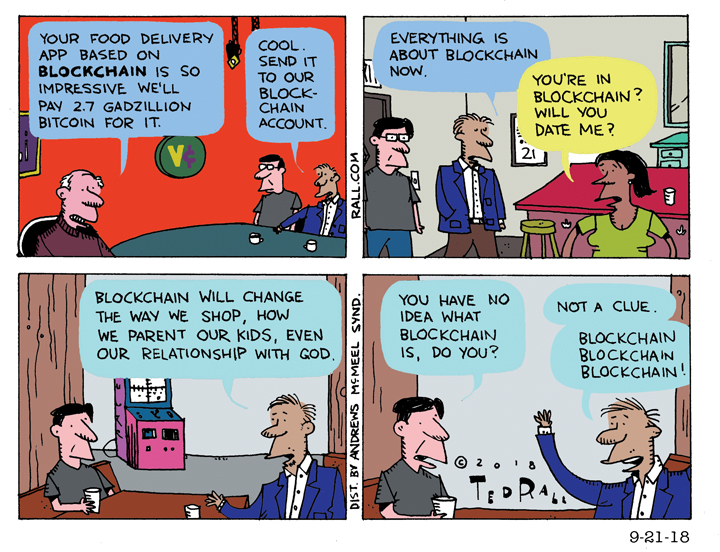

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of a new graphic novel about a journalist gone bad, “The Stringer.” Order one today. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

Ban drones.

Ban drones.