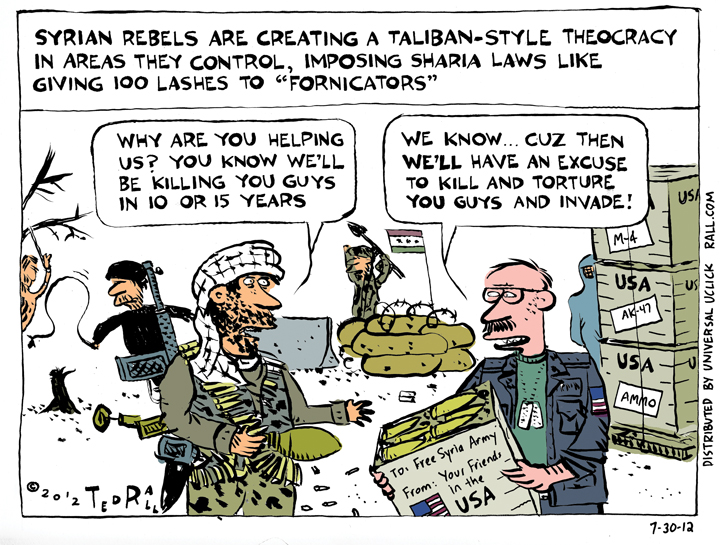

Free Syrian Army rebels, supported with money and arms by the United States, are establishing Taliban-style sharia law in the areas they control. Here we go again, replacing secular socialist governments with Islamist fanatics poised to become our future enemies.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: She Killed Afghans and Iraqis. Now She’s a Peace Child.

Susan Collins and the Precautionary Principle

Susan Collins is a U.S. senator. She is a Republican. She represents the people of Maine.

Senator Collins gets a lot of big things very wrong. Lots of people die because of Senator Collins.

She voted for the invasion of Iraq.

She voted for the invasion of Afghanistan.

Lots of people are dead. Because of her.

In 2007, four years into the Iraq War, when at least 100,000 Iraqis had been killed and the hunt for Saddam’s nonexistent weapons of mass destruction had been called off, Senator Collins nonetheless voted to extend the war.

She had another chance in 2008. Voted the same way. More deaths followed.

Late last year, one or two million dead civilians later, most U.S. occupation troops finally pulled out of Iraq. Remember the main argument for staying there, that we were fighting “them” over “there” to avoid having to fight them in the streets of American cities? It’s only been a few months, and anything can happen, but no one—not even Republicans like Senator Collins—seems worried about hordes of Iraqi jihadis rampaging through Baltimore. Obviously they were wrong.

The danger was false. Thus the war was unjustified.

What happens to Senator Collins after signing off on the mass murder of more than a million innocent people? Nothing. She’s planning a wedding.

Now she’s backing away from her other war.

“Despite the extraordinary heroism of our troops and the brilliance of our military leaders,” she wrote in a March 13th letter, “one has to wonder whether the corrupt central government [of Hamid Karzai] and with the history of Afghanistan, whether we can truly achieve the goal of a secure country.” The letter called for a speedier withdrawal than President Obama has announced.

Finally. Right about something.

Intelligence is the best wedding present ever!

Too bad it comes a decade late for the peoples of Afghanistan and Iraq. Who should, at bare minimum, enjoy the satisfaction of putting Senator Susan Collins (and those like her) on trial for waging wars of aggression and genocide.

Why am I picking on Collins? If there’s anything more appalling than unleashing death upon the innocent, recasting yourself as a “moderate” after your war sours in the polls is a major contender.

Back in 2001, when she cast votes in favor of dropping cluster bombs, full of brightly colored canisters designed to attract and blow up curious Afghan girls and boys, by the thousands and thousands, Senator Collins had a choice.

She could have listened to the experts. People who had been to Afghanistan. People on the Left.

There are two kinds of foreign policy analysts in the U.S. The right-wingers get interviewed and appointed to blue-ribbon presidential committees and are invariably wrong. The lefties, who more often than not turn out to be correct, get ignored.

After 9/11 the Left was against invading Afghanistan. (The Left doesn’t include Democrats, who were so disgustingly eager to be seen as “tough” on terrorism that they willingly went along with a war against a nation that had nothing to do with the attacks.)

No one likes invaders, but leftist analysts pointed out that Afghanistan’s history of slaughtering invading armies was unparalleled. U.S. forces, we warned, would face the usual Afghan reception. First the fighters would vanish into the population or into the mountains. They’d study us. Then they’d start picking us off two or three at a time. It’s what they did to the English (three times) and the Russians (once). We’d win every battle but it wouldn’t matter. They’d bleed us of young men and young women and political will.

Senator Collins could have read our essays and our books. If she did read them, she could have taken heed. She decided not to.

And so many people died.

After the Taliban were driven into the mountains and/or melted into the population, Republicans like Senator Collins thought they’d been vindicated. The Taliban are not really gone, we on the Left said. They’re just waiting. We’d been vindicated. The Right couldn’t see that. They wouldn’t listen.

Then the U.S. installed Hamid Karzai.

Those of us on the Left, who had actually been to Afghanistan and talked to actual Afghans, warned that Karzai had no political base. That his regime was hopelessly corrupt. That he was putting warlords, who ought to have been in prison for crimes they committed during the civil war, into positions of power and influence. That his government was universally despised.

We said that stuff ten years ago. So it’s a little galling to hear warmongers like Susan Collins talk about Karzai’s corruption and Afghanistan’s unique history. As if she were reporting information that came to light recently.

Senator Collins violated the precautionary principle—a precept enshrined in the law of various countries, including in Europe. A politician who proposes an action that might cause harm is obligated to present concrete evidence that it won’t cause harm. If she fails to meet that burden of proof, the proposal is rejected.

In the case of Collins and the other Republican and Democratic legislators, as well as the pundits and journalists who enabled them, all the evidence they needed that the wars against Afghanistan and Iraq would do more harm than good was as close as their computer or nearest bookstore.

Susan Collins ought to cancel the wedding and surrender at The Hague.

Failing that, the least she could do is shut up.

(Ted Rall’s next book is “The Book of Obama: How We Went From Hope and Change to the Age of Revolt,” out May 22. His website is tedrall.com.)

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: U.S. Double Standard: Gaddafi Bad, Karimov Good

The US shows its hypocrisy by accusing “tyrants” of human rights abuses while not owning up to supporting dictators.

“After four decades of brutal dictatorship and eight months of deadly conflict, the Libyan people can now celebrate their freedom and the beginning of a new era of promise,” President Obama said last week. The capture and death of Moammar Gaddafi prompted him and other U.S. officials to congratulate the Libyan people on their liberation from a despot accused of terrible violations of human rights, including the 1996 massacre of more than 1200 prison inmates.

The kudos were as much for the U.S. itself as Libya’s victorious Transitional National Council. After all, the United States played a decisive role in Gaddafi’s death. First President Obama put together the NATO coalition that served as the Benghazi-based rebels’ loaner air force. When the bombing campaign was announced in February, Gaddafi’s suppression of the human rights of protesting rebels was front and center: “The United States also strongly supports the universal rights of the Libyan people,” Obama said at that time. “That includes the rights of peaceful assembly, free speech, and the ability of the Libyan people to determine their own destiny. These are human rights. They are not negotiable. They must be respected in every country. And they cannot be denied through violence or suppression.” (No word on how police firing rubber bullets at unarmed, peaceful protesters at the Occupy movement in Oakland, California fits into that.)

And in the end, it was a Hellfire missile fired by a Predator drone plane controlled by the American CIA—in conjunction with an attack by a French fighter jet—that destroyed the convoy of cars Gaddafi and his entourage used to try to escape the siege of Sirte, driving him into the famous drainage pipe and into the hands of his tormentors and executioners.

American officials and media reports were right about Gaddafi’s human rights record: It was atrocious. They cautioned the incoming TNC to make human rights a priority: “The Libyan authorities should also continue living up to their commitments to respect human rights, begin a national reconciliation process, secure weapons and dangerous materials, and bring together armed groups under a unified civilian leadership,” Obama said. (No word on how Gaddafi’s execution fits in to that.)

Yet the very same week the United States was cozying up to another long-time dictator—one whose style, brutal treatment of prisoners, and notorious massacre of political dissidents is highly reminiscent of the deposed Libyan tyrant.

Like a business that maintains two sets of records, one for the tax inspector and the other containing the truth, the United States has two different foreign policies. Its constitution, laws and treaty obligations prohibit torture, assassinations, and holding prisoners without trial. In reality there are secret prisons like Guantánamo. Similarly, there are two sets of ethical standards in America’s dealing with other countries. Enemies are held to the strictest standards. Allies get a pass. This double standard is the number-one cause of anti-Americanism in the world.

In yet another display that exposes American foreign policy on human rights as hypocritical and self-serving, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton traveled to Uzbekistan to establish closer ties to the Central Asian republic’s president for life, Islam Karimov. Even as her State Department was ballyhooing the bloody conclusion of Gaddafi’s 42-year reign as a victory for freedom and decency, the former First Lady was engaged in the cynical Cold War-style of one of the worst human rights abusers in the world.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: Libya: The triumphalism of the US media

Obama and the US media are taking credit for Gaddafi’s downfall, but it was the Libyan fighters who won the war.

The fall of Moammar Gaddafi was a Libyan story first and foremost. Libyans fought, killed and died to end the Colonel’s 42-year reign.

No doubt, the U.S. and its NATO proxies tipped the military balance in favor of the Benghazi-based rebels. It’s hard for any government to defend itself when denied the use of its own airspace as enemy missiles and bombs blast away its infrastructure over the course of more than 20,000 sorties.

Still, it was Libyans who took the biggest risks and paid the highest price. They deserve the credit. From a foreign policy standpoint, it behooves the West to give it to them. Consider a parallel, the fall 2001 bombing campaign against the Taliban. With fewer than a thousand Special Forces troops on the ground in Afghanistan to bribe tribal leaders and guide bombs to their targets, the U.S. military and CIA relied exclusively on air power to allow the Northern Alliance to advance. The premature announcement that major combat operations had ceased, followed by the installation of Hamid Karzai as de facto president—a man widely seen as a U.S. figurehead—set the stage for what would eventually become America’s longest war.

As did the triumphalism of the U.S. media, who treated the “defeat” (more like the dispersing) of the Taliban as Bush’s victory. The Northern Alliance was a mere afterthought, condescended to at every turn by the punditocracy. To paraphrase Bush’s defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld, the U.S. went to war with the ally it had, not the one it would have liked to have had. America’s attitude toward Karzai and his government reflected that in many ways: snipes and insults, including the suggestion that the Afghan leader was mentally ill and ought to be replaced, as well as years of funding levels too low to meet payroll and other basic needs, thus limiting its power to metro Kabul and a few other major cities. In retrospect it would have been smarter for the U.S. to have graciously credited (and funded) the Northern Alliance with its defeat over the Taliban, content to remain the power behind the throne.

Despite this experience in Afghanistan “victory” in Libya has prompted a renewal of triumphalism in the U.S. media.

Like a slightly drunken crowd at a football match giddily shouting “U-S-A,” editors and producers keep thumping their chests long after it stops being attractive.

When Obama announced the anti-Gaddafi bombing campaign in March, Stephen Walt issued a relatively safe pair of predictions. “If Gaddafi is soon ousted and the rebel forces can establish a reasonably stable order there, then this operation will be judged a success and it will be high-fives all around,” Walt wrote in Foreign Policy. “If a prolonged stalemate occurs, if civilian casualties soar, if the coalition splinters, or if a post-Gaddafi Libya proves to be unstable, violent, or a breeding ground for extremists…his decision will be judged a mistake.”

It’s only been a few days since the fall of Tripoli, but high-fives and victory dances abound.

“Rebel Victory in Libya a Vindication for Obama,” screamed the headline in U.S. News & World Report.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: American Dogs Count More Than Afghan People

Helicopter Shootdown Story Unmasks Bigoted Media

New York Times war correspondent Dexter Filkins couldn’t help liking the young American soldiers with whom he was embedded in U.S.-occupied Iraq. Recognizing that, Filkins tried to maintain some professional distance. “There wasn’t any point in sentimentalizing the kids; they were trained killers, after all. They could hit a guy at five hundred yards or cut his throat from ear-to-ear. They had faith, they did what they were told and they killed people,” he wrote in his book of war vignettes, “The Forever War.”

Alas, he was all but alone.

All wars demand contempt for The Other. But the leaders of a country waging a war of naked, unprovoked aggression are forced to rely on an even higher level of enemy dehumanization than average in order to maintain political support for the sacrifices they require. Your nation’s dead soldiers are glorious heroes fallen to protect hearth and home. Their dead soldiers are criminals and monsters. Their civilians are insects, unworthy of notice. So it is. So it always shall be in the endless battle over hearts and minds.

Even by these grotesque, inhuman rhetorical standards, the ten-year occupation of Afghanistan has been notable for the hyperbole relied upon by America’s compliant media as well as its brazen inconsistency.

U.S. and NATO officials overseeing the occupation of Afghanistan liken their mission to those of peacekeepers—they’re there to help. “Protecting the people is the mission,” reads the first line of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Commander’s Counterinsurgency Guidance statement. “The conflict will be won by persuading the population, not by destroying the enemy. ISAF will succeed when the [Karzai government] earns the support of the people.”

Of course, actions speak louder than words. Since 2001 ISAF has been doing precious little protecting of anything other than America’s geopolitical interests, using Afghanistan as a staging ground for thousands of drone attacks across the border in Pakistan. Protecting Afghanistan civilians has actually been a low ISAF priority, to say the least. They’ve been bombing civilians indiscriminately, then lying about it, sometimes paying off bereaved family members with token sums of blood money.

The verbiage deployed by American officials, dutifully transcribed by journo-stenographers at official press briefings, sends nearly as loud a message as a laser-guided Hellfire missile slamming into a wedding party: Afghan lives mean nothing.

The life of an American dog—literally, as we’ll see below—counts more than that of an Afghan man or woman.

In the worst single-day loss of life for U.S. forces in Afghanistan, Taliban fighters shot down a Chinook CH-47 transport helicopter in eastern Wardak province with a rocket-propelled grenade on August 6th.

(I lifted that “worst single-day loss of life” phrase from numerous press accounts. The implication is obvious—the U.S. isn’t accustomed to taking losses. But tens of thousands of Afghans, possibly hundreds of thousands, have been killed in the war that began in 2001.)

Western media’s attitude toward the Afghans they are supposedly trying to “assist” was as plain as the headlines. “U.S. Troops, SEALs Killed in Afghanistan Copter Crash,” reported Time magazine. (SEALS are U.S. Navy commandos.) “31 Killed in Afghanistan Chopper Crash,” said the ABC television network. “31 Dead in Afghanistan Helicopter Crash,” shouted Canada’s National Post. (The number was later revised to 30.)

Eight Afghan government commandos died too. But dead Afghans don’t rate a headline—even when they’re working for your country’s puppet regime. As far as the American press is concerned, only 30 people—i.e., Americans—died.

An initial Associated Press wire service report noted that the dead included “22 SEALs, three Air Force air controllers, seven Afghan Army troops, a dog and his handler, and a civilian interpreter, plus the helicopter crew.”

The dog. They mentioned the dog.

And the dog’s handler.

After 9/11 American pundits debated the question: Why do they [radical Muslims] hate us [Americans] so much? This is why. It is official Pentagon policy not to count Afghan or Iraqi or Pakistani or Libyan or Yemeni or Somali dead, civilian or “enemy.” But “our” guys are sacred. We even count our dogs.

Lest you think that I’m exaggerating, that this was merely another example of a reporters larding his account with excessive detail, consider this maudlin missive by Michael Daly of the New York Daily News, one of the biggest newspapers in the United States:

“Among the SEALs were a dog handler and a dog that would remind outsiders of Cujo [a rabies-infected beast in one of Stephen King’s horror novels], but held a special place in the hearts of the squadron,” wrote Daly. “SEALs have a soft spot for their dogs, perhaps partly because a canine’s keen senses can alert them to danger and give them a critical edge. A dog also allows resolutely reticent warriors to express a little affection; you can pet a pooch, if not another SEAL.”

Get a grip, Mike. Lots of people like dogs.

“Many of the SEALs have a dog stateside,” continueth Daly. “To take one on a mission may be like bringing along something of home.”

Or maybe they just come in handy for Abu Ghraib-style interrogations.

Daly tortures and twists his cheesy prose into the kind of savage propaganda that prolongs a war the U.S. can’t win, that is killing Afghans and Americans for no reason, that most Americans prefer not to think about. Soon a group of elite commandos—members of Team Six, the same outfit that assassinated Osama bin Laden—become helpless victims of the all-seeing, all-powerful Taliban of Death. In Daly’s bizarre world, it is the Afghan resistance forces and their 1980s-vintage weapons that have all the advantages.

Note the infantile use of the phrase “bad guys.”

“The bad guys knew when the Chinook helicopter swooped down into an Afghan valley that it would have to rise once those aboard were done. All the Taliban needed to do was wait on a mountainside. The Chinook rose with a SEAL contingent that likely could have held off thousands of the enemy on the ground. The SEALs could do nothing in the air against an insurgent with a rocket.”

Helpless! One could almost forget whose country these Americans were in.

Or what they were in Wardak to do.

Early reports had the dead Navy SEALs on a noble “rescue mission” to “assist” beleaguered Army Rangers trapped under “insurgent” fire. Actually, Team Six was on an assassination assignment.

“The American commandos who died when their helicopter crashed in eastern Afghanistan were targeting a Taliban commander directly responsible for attacks on U.S. troops,” CNN television reported on August 7th. “Targeting” is mediaspeak for “killing.” According to some accounts they had just shot eight Talibs in a house in the village of Jaw-e-Mekh Zareen in the Tangi Valley. Hard to imagine, but U.S. soldiers used to try to capture enemy soldiers before killing them.

Within hours newspaper websites, radio and television outlets were choked with profiles of the dead assassins—er, heroes.

The AP described a dead SEAL from North Carolina as “physically slight but ever ready to take on a challenge.”

NBC News informed viewers that a SEAL from Connecticut had been “an accomplished mountaineer, skier, pilot and triathlete and wanted to return to graduate school and become an astronaut.”

What of the Afghans killed by those SEALs? What of their hopes and dreams? Americans will never know.

Two words kept coming up:

Poignant.

Tragedy (and tragic).

The usage was strange, outside of normal context, and revealing.

“Of the 30 Americans killed, 22 were members of an elite Navy SEAL team, something particularly poignant given it was Navy SEALS who succeeded so dramatically in the raid that killed Osama bin Laden,” said Renee Montaigne of National Public Radio, a center-right outlet that frequently draws fire from the far right for being too liberal.

Ironic, perhaps. But hardly poignant. Soldiers die by the sword. Ask them. They’ll tell you.

Even men of the cloth wallowed in the bloodthirsty militarism that has obsessed Americans since the September 11th attacks. Catholic News Service quoted Archbishop Timothy P. Broglio, who called the Chinook downing a “reminder of the terrible tragedy of war and its toll on all people.”

“No person of good will is left unmoved by this loss,” said the archbishop.

The Taliban, their supporters, and not a few random Afghans, may perhaps disagree.

This is a war, after all. Is it too much to ask the media to acknowledge the simple fact that some citizens of a nation under military occupation often choose to resist? That Americans might take up arms if things were the other way around, with Afghan occupation forces bombing and killing and torturing willy-nilly? That one side’s “insurgents” and “guerillas” are another’s patriots and freedom fighters?

Don’t news consumers have the right to hear from the “other” side of the story? Or must we continue the childish pretense that the Taliban are all women-hating fanatics incapable of rational thought while the men (and dog) who died on that Chinook in Wardak were all benevolent and pure of heart?

During America’s war in Vietnam reporters derided the “five o’clock follies,” daily press briefings that increasingly focused on body counts. Evening news broadcasts featured business-report-style graphics of the North and South Vietnamese flags; indeed, they immediately followed the stock market summary. “The Dow Jones Industrial Average was down 16 points in light trading,” Walter Cronkite would intone. “And in Vietnam today, 8 Americans were killed, 18 South Vietnamese, 43 Vietcong.”

Like the color-coded “threat assessment levels” issued by the Department of Homeland Security after 2001, the body counts became a national joke.

In many ways America’s next major conflict, the 1991 Gulf War, was a political reaction to the Vietnam experience. Conscription had been replaced by a professional army composed of de facto mercenaries recruited from the underclass. Overkill supplanted the war for hearts and minds that defined the late-Vietnam counterinsurgency strategy. And reporters who had enjoyed near total freedom in the 1960s were frozen out. Only a few trusted journos were allowed to travel with American forces in Kuwait and Iraq. They relied on the Pentagon to transmit their stories back home; one wire service reporter got back home to find that the military had blocked every single account he had filed.

Citing the five o’clock follies of Vietnam and declaring themselves incapable of counting civilian or enemy casualties, U.S. military officials said they would no longer bother to try. (Covertly, the bureaucracy continued to try to gather such data for internal use.)

Meanwhile, media organizations made excuses for not doing their jobs.

The UK Guardian, actually one of the better (i.e. not as bad) Western media outlets, summarized the mainstream view in August 2010: “While we are pretty good at providing detailed statistical breakdowns of coalition military casualties (and by we, I mean the media as a whole), we’ve not so good at providing any kind of breakdown of Afghan civilian casualties…Obviously, collecting accurate statistics in one of the most dangerous countries in the world is difficult. But the paucity of reliable data on this means that one of the key measures of the war has been missing from almost all reporting. You’ve noticed it too—asking us why we publish military deaths but not civilian casualties.”

No doubt, war zones are dangerous. According to Freedom Forum, 63 reporters lost their lives in Vietnam between 1955 and 1973—yet they strived to bring the war home to homes in the United States and other countries. And they didn’t just report military deaths.

There’s something more than a little twisted about media accounts that portray a helicopter shootdown as a “tragedy.”

A baby dies in a fire—that’s a tragedy. A young person struck down by some disease—that’s also a tragedy. Soldiers killed in war? Depending on your point of view, it can be sad. It can be unfortunate. It can suck. But it’s not tragic.

Alternately: If the United States’ losses in Afghanistan are “tragedies,” so are the Taliban’s. They can’t have it both ways.

“Tragedy Devastates Special Warfare Community,” blared a headline in USA Today. You’d almost have to laugh at the over-the-top cheesiness, the self-evident schmaltz, the crass appeal to vacuous emotionalism, in such ridiculous linguistic contortions. That is, if it didn’t describe something truly tragic—the death and mayhem that accompanies a pointless and illegal war.

On August 10th the U.S. military reported that they had killed the exact Talib who fired the RPG that brought down the Chinook. “Military officials said they tracked the insurgents after the attack, but wouldn’t clarify how they knew they had killed the man who had fired the fatal shot,” reported The Wall Street Journal.

“The conflict will be won by persuading the population, not by destroying the enemy.” But destroying the enemy is more fun.

(Ted Rall is the author of “The Anti-American Manifesto.” His website is tedrall.com.)

COPYRIGHT 2011 TED RALL

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: Tied to a Drowning Man

The interconnectedness of the world economy means that US economic woes will have severe effects on others.

During the Tajik Civil War of the late 1990s soldiers loyal to the central government found an ingeniously simple way to conserve bullets while massacring members of the Taliban-trained opposition movement. They tied their victims together with rope and chucked them into the Pyanj, the river that marks the border with Afghanistan. “As long as one of them couldn’t swim,” explained a survivor of that forgotten hangover of the Soviet collapse as he walked me to one of the promontories used for this act of genocide, “they all died.”

Such is the state of today’s integrated global economy.

Interdependence, liberal economists believe, furthers peace—a sort of economic mutual assured destruction. If China or the United States were to attack the other, the attacker would suffer grave consequences. But as the U.S. economy deteriorates from the Lost Decade of the 2000s through the post-2008 meltdown into what is increasingly looking like Marx’s classic crisis of late-stage capitalism, internationalization looks more like a suicide pact.

Like those Tajiks whose fates were linked by tightly-tied lengths of cheap rope, Europe, China and most of the rest of the world are bound to the United States—a nation that seems both unable to swim and unwilling to learn.

The collapse of the Soviet Union, a process that began in the 1970s and culminated with dissolution in 1991, had wide-ranging international implications. Russia became a mafia-run narco-state; millions perished of famine. Weakened Russian control of Central Asia, especially Afghanistan, set the stage for an emboldened and highly organized radical Islamist movement. Not least, it left the United States as the world’s last remaining superpower.

From an economic perspective, however, the effects were basically neutral. Coupled with its reliance on state-owned manufacturing industries to minimize dependence upon foreign trade, the USSR’s use of a closed currency ensured that other countries were not significantly impacted when the ruble went into a tailspin.

Partly due to its wild deficit spending on the gigantic military infrastructure it claimed was necessary to fight the Cold War—and then, after brief talk of a “peace dividend” during the 1990s, even more profligacy on the Global War on Terror—now the United States is, like the Soviet Union before it, staring down the barrel of economic apocalypse.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: How the US Media Marginalizes Dissent

The US media derides views outside of the mainstream as ‘un-serious’, and our democracy suffers as a result.

“Over the past few weeks, Washington has seemed dysfunctional,” conservative columnist David Brooks opined recently in The New York Times. “Public disgust [about the debt ceiling crisis] has risen to epic levels. Yet through all this, serious people—Barack Obama, John Boehner, the members of the Gang of Six—have soldiered on.”

Here’s some of what Peter Coy of Business Week magazine had to say about the same issue: “There is a comforting story about the debt ceiling that goes like this: Back in the 1990s, the U.S. was shrinking its national debt at a rapid pace. Serious people actually worried about dislocations from having too little government debt…”

Fox News, the Murdoch-owned house organ of America’s official right-wing, asserted: “No one seriously thinks that the U.S. will not honor its obligations, whatever happens with the current impasse on President Obama’s requested increase to the government’s $14.3 trillion borrowing limit.”

“Serious people.”

“No one seriously thinks.”

The American media deploys a deep and varied arsenal of rhetorical devices in order to marginalize opinions, people and organizations as “outside the mainstream” and therefore not worth listening to. For the most part the people and groups being declaimed belong to the political Left. To take one example, the Green Party—well-organized in all 50 states—is never quoted in newspapers or invited to send a representative to television programs that purport to present “both sides” of a political issue. (In the United States, “both sides” means the back-and-forth between center-right Democrats and rightist Republicans.)

Marginalization is the intentional decision to exclude a voice in order to prevent a “dangerous” opinion from gaining currency, to block a politician or movement from becoming more powerful, or both. In 2000 the media-backed consortium that sponsored the presidential debate between Vice President Al Gore and Texas Governor George W. Bush banned Green Party candidate Ralph Nader from participating. Security goons even threatened to arrest him when he showed up with a ticket and asked to be seated in the audience. Nader is a liberal consumer advocate who became famous in the U.S. for stridently advocating for safety regulations, particularly on automobiles.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: Censorship of Civilian Casualties in the US

US mainstream media and the public’s willful ignorance is to blame for lack of knowledge about true cost of wars.

Why is it so easy for American political leaders to convince ordinary citizens to support war? How is that, after that initial enthusiasm has given away to fatigue and disgust, the reaction is mere disinterest rather than righteous rage? Even when the reasons given for taking the U.S. to war prove to have been not only wrong, but brazenly fraudulent—as in Iraq, which hadn’t possessed chemical weapons since 1991—no one is called to account.

The United States claims to be a shining beacon of democracy to the world. And many of the citizens of the world believes it. But democracy is about responsiveness and accountability—the responsiveness of political leaders to an engaged and informed electorate, which holds that leadership class accountable for its mistakes and misdeeds. How to explain Americans’ acquiescence in the face of political leaders who repeatedly lead it into illegal, geopolitically disastrous and economically devastating wars of choice?

The dynamics of U.S. public opinion have changed dramatically since the 1960s, when popular opposition to the Vietnam War coalesced into an antiestablishmentarian political and culture movement that nearly toppled the government and led to a series of sweeping social reforms whose contemporary ripples include the recent move to legalize marriage between members of the same sex.

Why the difference?

Numerous explanations have been offered for the vanishing of protesters from the streets of American cities. First and foremost, fewer people know someone who has gotten killed. The death rate for U.S. troops has fallen dramatically, from 58,000 in Vietnam to a total of 6,000 for Iraq and Afghanistan. Many point to the replacement of conscripts by volunteer soldiers, many of whom originate from the working class, which is by definition less influential. Congressman Charles Rangel, who represents the predominantly African-American neighborhood of Harlem in New York, is the chief political proponent of this theory. He has proposed legislation to restore the military draft, which ended in the 1970s, four times since 9/11. “The test for Congress, particularly for those members who support the war, is to require all who enjoy the benefits of our democracy to contribute to the defense of the country. All of America’s children should share the risk of being placed in harm’s way. The reason is that so few families have a stake in the war which is being fought by other people’s children,” Rangel said in March 2011.

War is extraordinarily costly in cash as well as in lives. By 2009 the cost of invading and occupying Iraq had exceeded $1 trillion. During the 1960s and early 1970s conservatives unmoved by the human toll in Vietnam were appalled by the cost to taxpayers. “The myth that capitalism thrives on war has never been more fallacious,” argued Time magazine on July 13, 1970. Bear in mind, Time leaned to the far right editorially. “While the Nixon Administration battles war-induced inflation, corporate profits are tumbling and unemployment runs high. Urgent civilian needs are being shunted aside to satisfy the demands of military budgets. Businessmen are virtually unanimous in their conviction that peace would be bullish, and they were generally cheered by last week’s withdrawal from Cambodia.”

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: The US Love Affair with Drones

One of the pleasures of traveling through the developing world is that things develop. They change. There’s always something new.

Afghanistan is, depending on one’s point of view, developing, deteriorating, or doing both at once.

Example: Last August found me and two fellow Americans in a hired taxi zooming past bombed-out fuel trucks through Taliban-held Kunduz, a city in northern Afghanistan near the Tajik border. The sense of menace was palpable, but our driver seemed calm.

Then his face darkened. We were passing into the flatlands east of Mazar-i-Sharif. We saw nothing but dirt, dust and rocks, all the way to the horizon. Yet our driver was nervous. He scanned this bleak landscape. “Motorcycles,” he said. “I am looking for the motorcycles.”

The adaptable neo-Taliban increasingly rely on the classic tactics of guerilla warfare. Rather than hold territory, these postmodern Islamists-cum-gangsters rely on hit-and-run strikes using something I hadn’t seen in 2001: motorcycles. Like a scene from the Kazakh film epic about Genghis Khan updated by Quentin Tarantino, squadrons of bearded bikers are terrorizing Afghanistan’s newly/cheaply paved highways.

I call them the Talibikers.

One of the more intriguing revelations in last year’s WikiLeaks data dump was that the Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence spy agency has been supplying the Taliban with thousands of Pamir dirtbikes, including a 2007 shipment of 1,000 to the Waziristan-based network led by Mawlawi Jalaludin Haqqani. Talibs ride the Pamirs and their preferred brand, the Honda 125 and its Chinese knock-offs, to assassinations. They launch attacks on highways from bases in villages 10 to 15 kilometers away.

The Talibikers speed across the desert in great clouds of dust, “Mad Max” style, to ambush and bomb fuel trucks. There they set up checkpoints where they shakedown travelers for cash. Sometimes they kidnap motorists and demand ransom payments from their families. By the time the hapless Afghan national police shows up, the resistance fighters are long gone.

An early report on the Talibikers appeared in the Telegraph in 2003. “The motorcycles have played a key role in Taliban hit-and-run operations in the south of the country where the campaign against international troops and aid workers has intensified,” the British newspaper reported in November of that year. “In the latest incident, a Frenchwoman working for the United Nations was shot dead this month by the pillion passenger on a motorcycle in the south-eastern town of Ghazni. The Taliban later claimed responsibility for the attack. In another recent attack, a group of motorcyclists opened fire on an aid convoy near Kandahar, killing four Afghans. In August, two motorcyclists threw a grenade into the Kandahar compound of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, damaging the building but causing no injuries.”

ISI-funded motorbikes continue to play a vital role in the Taliban’s war to drive U.S. and NATO occupation troops out of Afghanistan. “Day and night, Taliban assassins on motorbikes hunt their victims, often taunting them over the telephone before gunning them down in the city’s streets,” Paul Watson wrote in The Star, a newspaper in Canada in February 2011. “They are working their way through lists, meticulously killing off people fingered as collaborators with the Afghan government or its foreign backers…The build-up of Afghan police and soldiers, and foreign troops, in and around Kandahar city over recent months has improved security, but agile and coldly efficient motorbike death squads remain active.”

Mass attacks continue as well. “About 100 Taliban fighters on motorcycles attacked a northern Afghan village that was working to join the government-sponsored local police program against the insurgency, killing one villager, police said Wednesday. An ensuing battle also left 17 militants dead,” the Associated Press reported in May 2011.

There are fewer than 10,000 Talibikers in Afghanistan. They could be eliminated—if the U.S. and NATO stopped focusing on assassination-by-drone and instead used the same technology to increase security.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) date to the maiden flight of the now-familiar Predator drones in 1994. After 9/11 the United States became addicted to the Predator and its successor, the Reaper.

Today the Air Force and CIA have at least 7000 UAVs in service around the world, representing the biggest and most visible presence of the U.S. military in Pakistan, Somalia, Libya, and Yemen. This trend is likely to accelerate. As of March 2011 the U.S. Air Force was training more remote drone “pilots” than those for conventional planes. Next year the Pentagon wants $5 billion just for drones.

Drones are getting smaller and more numerous. “One of the smallest drones in use on the battlefield is the three-foot-long Raven, which troops in Afghanistan toss by hand like a model airplane to peer over the next hill,” according to The New York Times. “There are some 4,800 Ravens in operation in the Army, although plenty get lost.” More on this later.

It’s easy to see why generals and politicians are so enthusiastic. The pilotless planes, guided by operators manning a joystick at military and pseudomilitary agencies such as CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia and armed by Xe, the private contractor formerly called Blackwater, are relatively cheap. A Predator costs $4.5 million; an F-22 Raptor fighter jet runs $150 million a unit. Peter Singer, director of the 21st Century Defense Initiative at the Brookings Institution, cites the “three Ds.” Drones are “dull” because they can patrol empty stretches of barren land 24 hours a day. They’re “dirty” because they can fly in and out of toxic clouds, including radiation. Most appealingly, they are “dangerous” because the absence of a pilot eliminates the risk that a pilot—they cost millions to train–will be killed or captured by enemy forces. UAVs exploit the element of surprise: though relatively unobtrusive, they fire supersonic armor-piercing Hellfire missiles capable of striking a target as far as five miles away.

“People who have seen an air strike live on a monitor described it as both awe-inspiring and horrifying,” The New Yorker magazine reported in 2009. “‘You could see these little figures scurrying, and the explosion going off, and when the smoke cleared there was just rubble and charred stuff,’ a former C.I.A. officer who was based in Afghanistan after September 11th says of one attack. (He watched the carnage on a small monitor in the field.) [Bleeding] human beings running for cover are such a common sight that they have inspired a slang term: ‘squirters.'”

Charming.

According to the Pentagon, drones hit their targets with 95 percent accuracy. The problematic question is: who are their targets?

Thousands of people have been rubbed out by drones since 9/11.

(Press accounts document between 1400 and 2300 extrajudicial killings by allied forces, mostly in the Tribal Areas adjacent to Pakistan’s Northwest Frontier Province. According to media reports cited by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, at least 957 Pakistanis were murdered by American drones in 134 airstrikes during the year 2010 alone. Since the media only learns about a fraction of these “secret” killings, the real number must be many times higher.)

Since the Pakistani government does not officially acknowledge, much less authorize, such attacks, they are illegal acts of war.

Political philosopher Michael Walzer asked in 2009: “Under what code does the CIA operate? I don’t know. There should be a limited, finite group of people who are targets, and that list should be publicly defensible and available. Instead, it’s not being publicly defended. People are being killed, and we generally require some public justification when we go about killing people.”

One would think.

Legal or not, Christine Fair of Georgetown University says the U.S. doesn’t use drone planes indiscriminately: “You have lawyers, you have targeteers, you have intelligence operatives, you actually have pilots who are manning the drones. These are not 14-year-old kids right out of basic training, playing around with a joystick,” she told National Public Radio.

In the real world, it’s often hard to tell the difference. There’s no doubt that drone operators make mistakes. In April 2011, for example, two American marines were killed by a Predator in Afghanistan.

Of course, the majority of victims are local civilians. In Afghanistan and Pakistan drone strikes have killed countless children and wiped out so many wedding parties that it’s become a sick joke. Estimates of the civilian casualty rate range from a third (by the New America Foundation) to 98 percent (terrorism expert Amir Mir). There is no evidence that a single “terrorist” has ever been killed by a drone—only the say-so of U.S. and NATO spokesmen.

Errors are inherent due to the principal feature of the technology: remoteness. Manned aerial warfare is notoriously inaccurate; pilots zooming close to the speed of sound tens of thousands of feet above the ground have little idea who or what they’re shooting at. Drone operators have even less information than old-school pilots. Like a submariner peering out of a periscope, they are supposed to decide whether people live or die based on fuzzy images through layers of glass. They call it the “soda straw.”

Nowadays, staffing is a troubling challenge: it takes 19 analysts to study images and other data from one drone. In the future, a war could eliminate unemployment entirely: it will take approximately 2000 men and women to process information from one drone equipped with “Gorgon stare” optics capable of scanning an entire city at once.

There’s also a huge gap in education, experience and culture. Virtual warriors require simple rules that don’t apply when trying to kill jihadis. At the beginning of the U.S. war against Afghanistan in 2001, for example, it was an article of faith within the Pentagon that men wearing black long-tailed turbans were Talibs. Dozens, possibly hundreds, of noncombatants were killed because of this incorrect assumption. In February 2002 a drone operator blew up a man because he was tall—as was Osama bin Laden. In fact, he and two other men killed were poor villagers gathering scrap metal. Again, this doesn’t address the broader issue of whether it’s OK to murder people simply because they are members of the Taliban.

At least as interesting as the choice of target is whom the U.S. does not try to kill: the Talibikers.

Unlike the wedding parties, houses and tribal councils that have been mistakenly incinerated by the aptly-named Hellfire missiles, Taliban bike gangs are easy to identify from the air. One or two hundred dirtbikes speeding across the desert toward a truck on an Afghan highway are unmistakable. Most Afghans, even those who oppose the U.S. occupation, fear the Talibikers and resent being robbed at impromptu checkpoints. There have been a few scattershot drone strikes, nothing more. Why don’t the CIA whiz kids make these easily identified fighters a primary target?

I posed the question to Afghan government officials. They told me that the same U.S. military that blows $1 billion a week on the war won’t lift a finger to save Afghan lives by providing basic security. “Afghan lives are worth nothing to the Americans,” a provincial governor told me.

Last week the United Nations announced that civilian casualties were up 15 percent during the first six months of 2011. If the same rate continues, this will be the worst year of the ten-year-long American occupation.

A well-placed U.S. military source confirms that Afghan security “isn’t a priority, it isn’t even much of a passing thought.” Contrary to President Obama’s claim that U.S. is in Afghanistan in order to prevent the country from becoming a base for Al Qaeda and other extremist groups and to combat opium cultivation, he says that Afghanistan isn’t about Afghanistan at all. “Afghanistan is a staging area for drone and other aerial strikes in western Pakistan,” he says. “Nothing more, nothing less. Afghanistan is Bagram [airbase].”

Under Obama the death toll has risen, worsening relations between the White House and its puppet president, Hamid Karzai. Beyond the horror of the deaths themselves, it would be impossible to overstate the contempt that ordinary people in nations like Afghanistan and Pakistan feel for the drone program. “Americans are cowards” was one refrain I heard last year. Real soldiers risk their lives. They do not send buzzing machines to kill people half a world away…people they know nothing about.

Back in 2002, former CIA general counsel Jeffrey Smith worried about blowback. “If [Taliban leaders and soldiers are] dead, they’re not talking to you, and you create more martyrs,” he noted. Ongoing drone attacks “suggest that it’s acceptable behavior to assassinate people…Assassination as a norm of international conduct exposes American leaders and Americans overseas.”

These days, the media gives little to no time or space to such concerns. Americans have moved into postmorality. Right or wrong? Who cares?

Recently international law professor Mary Ellen O’Connell of Notre Dame University said that the new reliance on drones could prompt an already militaristic superpower to fight even more wars of choice. “I think this idea that somehow this technology is allowing us to kill in more places and…aim at more targets is for me the fundamental ethical and legal problem.”

Meanwhile, adds Mary Dudziak of the University of Southern California’s Gould School of Law: “Drones are a technological step that further isolates the American people from military action, undermining political checks on…endless war.” No casualties? No problem.

Meanwhile, at a “microaviary” inside an air force base north of Dayton, Ohio, “military researchers are at work on another revolution in the air: shrinking unmanned drones, the kind that fire missiles into Pakistan and spy on insurgents in Afghanistan, to the size of insects and birds,” approvingly reports The New York Times.

Ted Rall is an American political cartoonist, columnist and author. His most recent book is The Anti-American Manifesto. His website is rall.com.