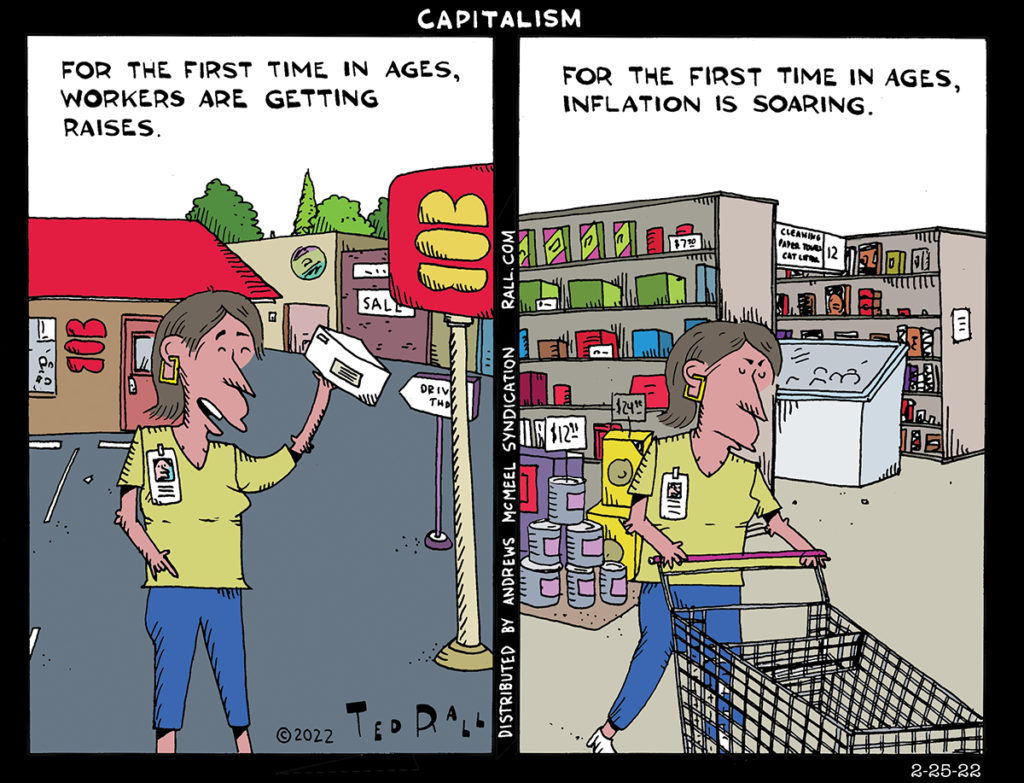

If you are an American worker who is finally getting a higher salary after decades of losing ground to inflation, there is something especially dispiriting about seeing your raise get completely me up by inflation that is increasing even faster.

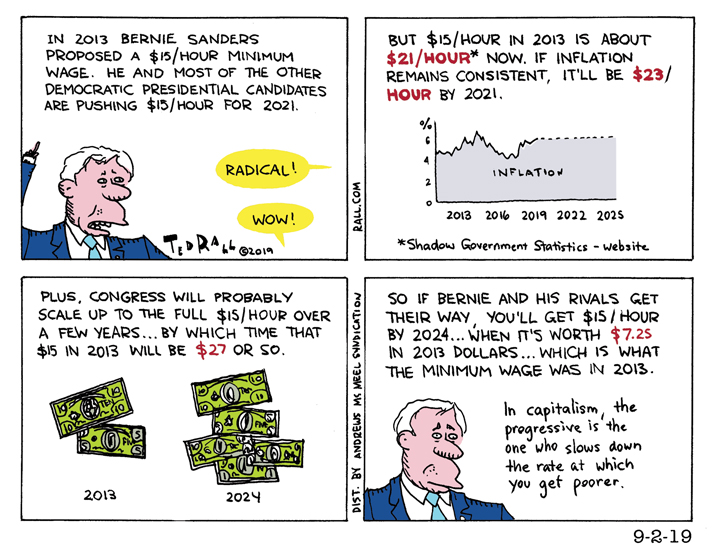

Bernie Sanders Is the Best on the Minimum Wage and It’s Not Near

On the issue of the minimum wage, no top contender for the presidency has been as aggressive as Bernie Sanders. But for workers, that’s not nearly enough. For the last six years, Sanders has been pushing a $15 an hour minimum wage. That’s a major improvement over the current rate but it’s not nearly enough to keep up with inflation. Even under Sanders, workers would, at best, fail to lose more ground. They wouldn’t gain anything. Just another case study of how capitalism is not reformable.

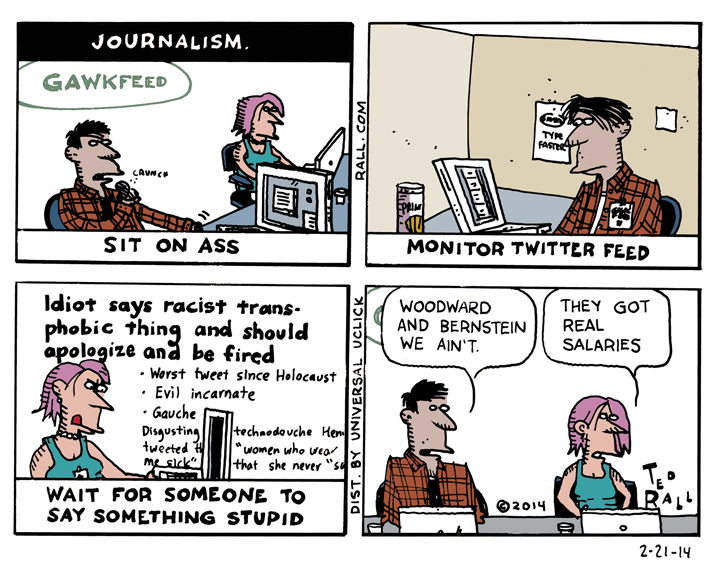

The New Journalism

Not long ago, journalists were expected to work stories by getting out of the office and tracking them down. The new breed of online journalists who have replaced them sit on their butts, monitoring tweets in the hope that some celebrity or politician will say something stupid so they can trash them. This is what, in an age of minute budgets, passes for journalism.

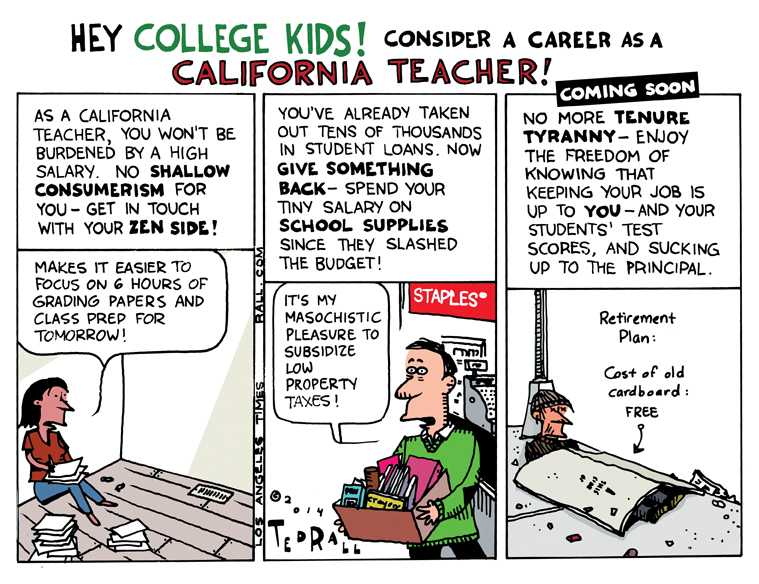

LOS ANGELES TIMES CARTOON: The War on Teacher Tenure

This week:

My mother retired recently from teaching under pretty much the best possible working conditions one could expect in an American high school: she taught high school French in an Ohio suburb whose demographics are at least 90% white, ranging from middle to upper-middle class. By the end of her career, she was relatively decently paid. Her students weren’t hobbled by poverty or challenged due to not having mastered English. Since French was an elective, her kids pretty much wanted to be there (though getting cut due to low enrollment was a worry).

Still, it was a tough job. Sure, class is 8 to 3 and she got those long summer vacations. But I remember watching her get up at 5:45 so she could prepare for class during the calm before the morning bell. She rarely got home before 5 — there’s always some meeting to attend — and then she had to grade papers and prepare the next day’s classes. Teaching is a performance. You’ve got roughly six hours to fill, keeping the kids entertained and engaged enough to get them to pay attention to what they need to learn. It’s exhausting, especially when you were up until 11 the night before correcting tests and averaging grades.

The summers were nice, but my mom spent the last half of June and the better part of July crashed out, recuperating. As for the last half, it wasn’t like we could afford to go on any trips. Not on a crummy teacher’s salary. For the first few decades of a teacher’s career, the pay is crap.

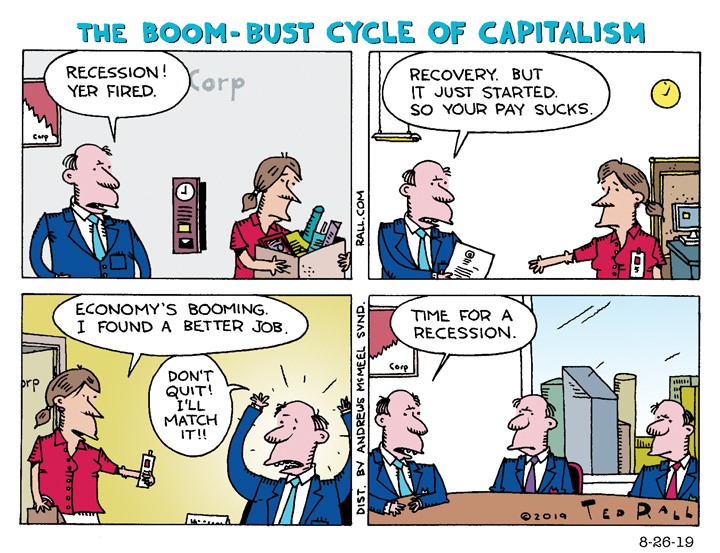

Raises don’t keep up with inflation. Parents constantly complain, often without cause. Administrators constantly lard on more responsibility, more paperwork, more rules, always more stuff to do on the same crummy salary. Moreover, budgets are always being cut. Even in lily-white districts like my mom’s, teachers find themselves hitting the office supply store to buy stuff for their students — out of that crummy paycheck.

During the last few decades, particularly since Reagan, the Right has waged war on teachers and their unions. From No Child Left Behind to the sneakily anti-unon, anti-professionalization outfit Teach for America to the Common Core, conservatives are holding teachers accountable for their kids’ academic performance. Sometimes it’s fair. Sometimes it’s not. Even the smartest and hardest-working teacher is going to have trouble getting good state test scores out of a classroom full of kids brutalized by abuse at home, poverty, crime and neglect.

The latest skirmish in the edu-culture war is over tenure, and it’s unfolding this week in Los Angeles County Superior Court. Superintendent John Deasy of the Los Angeles Unified School District is supporting a lawsuit, backed by a right-wing front group called Students Matter, that would eliminate teacher tenure as we know it in California. Tenure, say nine students recruited as plaintiffs, makes it too hard to fire bad teachers.

Not so fast, counter the unions. “Tenure is an amenity, just like salary and vacation, that allows districts to recruit and retain teachers despite harder working conditions, pay that hasn’t kept pace and larger class sizes,” James Finberg, a union lawyer, told the court. It also protects workers/teachers from being fired over their political beliefs, gender and religion — or just being too “mouthy,” i.e., speaking out against budget cuts.

As a parent, it’s easy to see why it would be good to make it easier to fire bad teachers. As the son of a hard-working teacher, it’s easier to see why teachers would need tenure. As in any other workplace, which teachers are judged “good” or “bad” falls to the boss — in this case, usually the school principal — who may or may not render a fair judgment free of personal bias based on personality or philosophy. Accusations of wrongdoing or incompetence levied by parents may or may not be fair.

Until my mom got tenure, she was afraid of disciplining students. She didn’t dare be active in her union. She didn’t want to reveal, in a Republican town, that she was a Democrat. Tenure didn’t make her lazy after she got it, but it did make her more relaxed, less terrified of her boss. Which made her a better, wiser, smarter teacher.

Tenure doesn’t prevent districts from firing teachers. It makes it hard. (Not impossible: two percent of teachers get fired for poor performance annually.) Which, frankly, is something that every worker who has ever experienced an unfair review should be able to empathize with. If anything, the only thing wrong with tenure is that only teachers can get it.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Why Does the Military Treat Soldiers Like Children?

Why Doesn’t the Pentagon Let Its Employees Be All They Can Be?

The U.S. military isn’t supposed to allow child soldiers to enlist (though reality can differ). So why does it treat recruits like children?

Other than religious avocations, it’s impossible to think of another major employer that asks as much of prospective workers as the Pentagon, yet offers so little. Salaries are lower than for comparable private-sector jobs. The skills one acquires don’t translate easily to other fields. The risks couldn’t be higher. But most baffling, for a force supposedly dedicated to defending our freedom, is that they get little freedom of their own.

You’ve heard the drill sergeant line in movie boot-camp scenes: “You are now the property of the United States of America.” That’s true. Once signed up, soldiers and sailors can be assigned anywhere, to any job, completely at their commanders’ discretion. Sometimes they take your skills, desires or ambitions into consideration. Not always.

Active duty, recruiters tell young men and women, lasts two to five years — after which they’re supposed to wind up in the reserves, free to go home unless there’s a national emergency. But the President can invoke the “stop-loss” provision, which means you can get stuck as long as eight.

It’s time for the military to catch up to the modern workplace.

American workers are getting more of a raw deal in many ways: lower wages and benefits, companies that ignore the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, no more pensions. Yet the fraying of the postwar labor-management social contract has also provided employees with greater flexibility. You may have to work three crappy jobs to make ends meet, but crappy jobs are easy to replace. You can move to another city and probably find three crappy jobs there. You certainly don’t have to worry about one of your crappy employers shipping you off to Afghanistan, much less coming home in a coffin.

The military’s insistence on treating its workers like property to be disposed of at whim is obsolete, making it increasingly difficult — even in a high-unemployment economy — to compete for recruits.

One example making recent headlines is the Air Force’s increasingly severe shortfall of fighter pilots. A new signing bonus totaling nearly a quarter million bucks (albeit spread over nine years), isn’t enough to compensate for starting salaries ($34,500 to $97,400) — not when the airlines are paying a median salary of $103,210 to commercial jet pilots. Nor are benefits like lower taxes and on-base housing.

“The military is difficult on the family with all the moving around,” Rob Streble, a former Top Gun and an official of the union that represents US Airways pilots, told The Los Angeles Times. “I added more stability by joining the airline.”

“People have no idea how hard it is when you have to move your family all the time,” admits John Wigle, a former F-15 pilot who is now a program analyst in the USAF’s operations, plans and requirements directorate.

Freedom was a determining factor for me.

The recruiter manning the desk at the Army Recruiting Office in Kettering, Ohio was way into me when I walked through the door at age 18. I had what they’re looking for: I was human, sentient, and ambulatory. I was also a catch: a straight-A engineering student who’d gone to an Ivy League school on full scholarship. When Reagan slashed financial aid for me and millions of other college students, I considered other options.

I aced the Army aptitude test. This didn’t surprise me, considering the lugs sitting in the test center next to me. Anyway, I test great. I drew the attention of a big über recruiter for the entire Midwest who wouldn’t stop calling. He made a lot of promises. We’ll fast-track you for officer! When you get out, we’ll pay your college tuition! What’s that, you want to draw cartoons for Stars and Stripes, just like Bill Mauldin during World War II? Sure, why not?

As a child of divorce, I’d learned to get promises in writing. Which, of course, military recruiters can’t and won’t do. (At the time, the Army paid “up to” $5,000 a year for college. Columbia was $13,000.) Sure, despite Reagan’s efforts, we weren’t at war. So getting killed was unlikely. But they could send me anywhere in the world, assign me to any job they wanted (from a military website today: “The Military will make every effort to match your interests and aptitudes with its needs. However, job assignments are ultimately made based on Service needs, as well as individual skills and test scores”), and the bottom line was, there’d be nothing I could do but salute and say yessir. That was the end of my flirtation with a military career. I wanted the basic freedom to choose where I lived and what I did for work.

I’m not alone. 89% of young Americans say they’d never consider a military career.

It will be a bummer for military officers, by temperament the biggest control freaks ever, but sooner or later they’re going to have to face reality: slavery is over. If you want to find quality sailors and soldiers, you have to treat them like adults. Let recruits choose their positions and where they live. Act like they’re workers. Which they are. For example, why can’t soldiers put in for vacation as opposed to applying for leave? If their chosen job is no longer needed, fine — they should be free to go. Yes, even during wartime — at least during the optional wars of choice the United States has fought since 1945.

During an invasion or serious attack against the U.S. by another nation, obviously, all bets are off. But don’t worry — that hasn’t happened since 1812.

(Ted Rall’s website is tedrall.com. His book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan” will be released in 2014 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

COPYRIGHT 2013 TED RALL

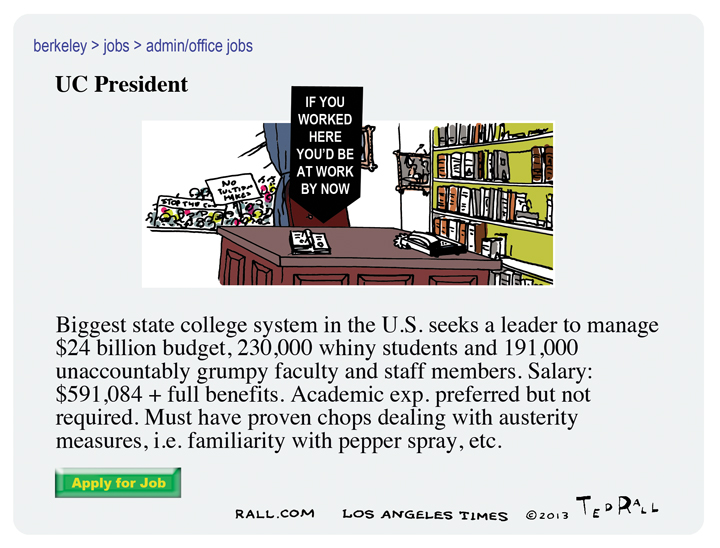

LOS ANGELES TIMES CARTOON: Help Wanted – UC President

I draw cartoons for The Los Angeles Times about issues related to California and the Southland (metro Los Angeles).

This week: The University of California is reaching outside of academia in its search for a new President for the nation’s largest state college system.