When I was young, I knew a lot about old people. Especially about old people I knew personally: members of my family, my mother’s contemporaneous older friends, teachers, clients on my paper route.

It wasn’t a choice. When I was young, no one asked whether I was interested about events that significantly preceded my birth. They just talked. My mom told me countless detailed stories about her childhood growing up during the Nazi occupation of France; many if not most of these tales of woe were repeated despite my reminders that I was already familiar with them. I was expected to listen as the schoolteacher got shot, the cat was abandoned and the Allied tanks rolled in.

Children, teenagers and young adults were expected less to be seen and not heard than to listen politely nodding their heads as their elders described watching the Beatles arrive at Idlewild (on black-and-white TV with rabbit ears, natch), where they were when they heard that Kennedy had been shot and, in the case of my seventh-grade homeroom teacher, what it was like to be in the convention hall when FDR accepted the Democratic nomination.

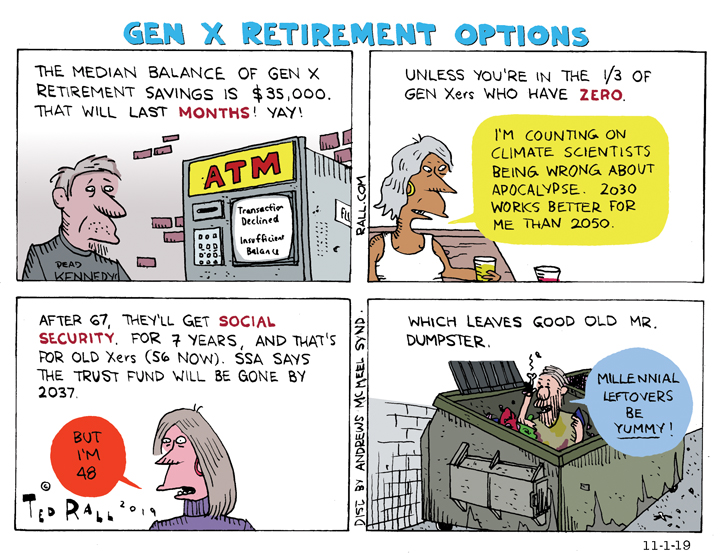

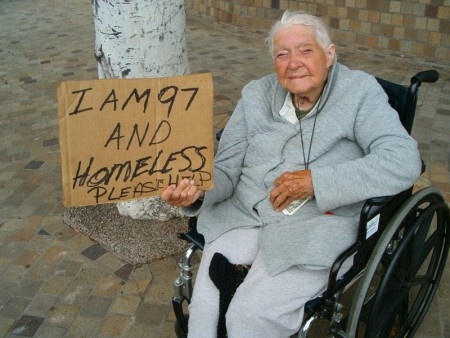

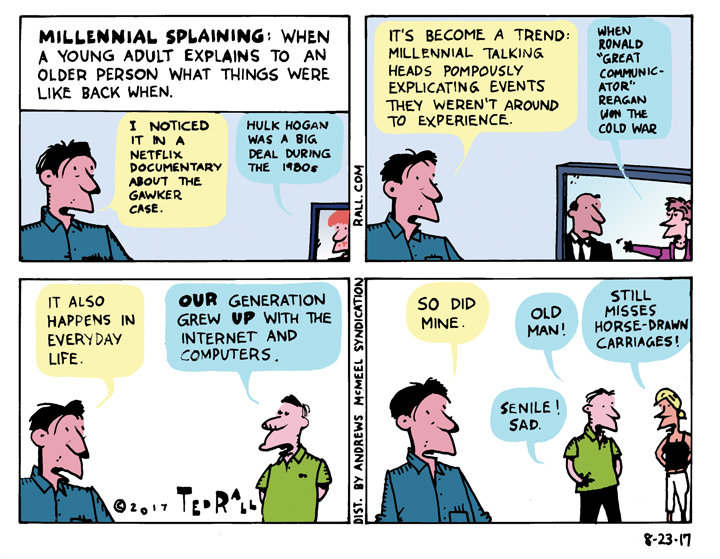

Pop culture, politics and personal histories from decades prior persisted in a way that doesn’t seem possible today, when youth culture and the Internet have delivered a clear message to older generations like mine (I’m an old Gen Xer) that our stories are neither wanted nor sought out.

And sought out they would have to be. Unlike my Baby Boomer babysitter who taught my nine-year-old self hippie slang, how to curse and how much fun she’d had at a free-love commune, and also unlike my Silent Generation father who schooled me on Jack Benny and Benny Goodman, we members of Generation X survived our histories of childhood neglect and adulthood underappreciation only to graduate into our later years assuming that no one cares about us and no one ever will. So yeah, there was that time I stood three feet away from Johnny Thunders when he gave his last concert and the hilarious lunch I had with Johnny Ramone and the time Ed Koch gave me the finger after I bounced a bottle off the roof of his limousine, but I’m pretty sure nobody under age 45 cares.

As the author and psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist says: “In the old days young people went to university to learn from people who were perhaps three times their age and had read an enormous amount. But nowadays they go in order to tell those older people what they should be thinking and what they should be saying.”

Or maybe younger people would care. But they’d have to ask. And I’d have to be convinced that they weren’t just being polite. Probably not going to happen.

Whatever the cause is, and what I’ve written so far is no doubt only part of the reason, there is probably less familial, cultural and popular history being transferred from older generations to younger ones than ever before. Changes in technology and education are contributing to our failure to pass on knowledge and wisdom.

If you don’t know where you came from, you don’t know who you are.

Generation Z, for example, never learned to write in cursive. Which means they can’t read it. In the same way that Ataturk’s decision to abolish Arabic script in favor of a Latinate alphabet suddenly made hundreds of years of incredible literature inaccessible to Turks after 1928 and Mao’s simplified Chinese characters meant that only scholars can read older texts, newer generations of Americans won’t be able to read an original copy of the Declaration of Independence or a letter from their grandmother.

Similarly, the dark ages of photography are well upon us. Though it has never been cheaper or easier to take or store or transmit a high-resolution photo, the number that are likely to pass from one generation to the next has never been smaller. When mom dies, her smartphone password usually dies with her. Even when obtaining a court order is not required, how likely is a grieving child to sort through an overwhelming volume of photos, few of them worth preserving, and have the presence of mind to carefully store the keepers somewhere where their own children will be easily be able to access them someday? And let’s not mention the digital disasters that can instantly wipe out entire photo archives.

For all their shortcomings—fading, development costs—film-based photos survived precisely because they were more expensive, which made them precious, which prompted people to store them in albums. We’ve all read stories about how victims of a flood or fire sometimes only escaped with one possession, the family photo album.

I’m grateful for all the old stuff old people told me whether or not I wanted to hear it. Some stuff was pretty enlightening, like the couple on my paper route where the husband had fought in World War I and still had his gas mask on which he had written the names of each little French village through which he and his squadron had passed. They invited me in for tea when I came to collect my money. It’s one thing to read about the horrors of mustard gas. Holding that contraption in my hands made it feel real.

Other things I picked up probably didn’t teach me much of anything at all. Still, it was pretty interesting to learn how to use an old-fashioned adding machine, Victrola record player and self-playing piano one of my neighbors had in her garage. My mom taught me how to use carbon paper; recalling the fact that businesses and government agencies routinely made numerous copies to be distributed to different files proved useful when I researched my senior thesis at the National Archives.

When I complain about a problem, I like to offer a solution. But I’m not entirely sure that the fact that billions of yottabytes worth of human knowledge is getting memory-holed, mostly because Millennials and Gen Zers aren’t particularly interested is necessarily a problem. Maybe they don’t need that stuff to try to save themselves from climate change or killer asteroids.

What I do know, if indeed it is a problem, is that it is one without a possible solution. In the same way that streets would be clean if nobody littered but people always do so they never are, there is no way to convince today’s 30-year-olds that they should take an interest in what today’s 60-year-olds have to say.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” William Faulkner wrote. But he’s so old, he’s dead.

Nowadays, even the present is past.

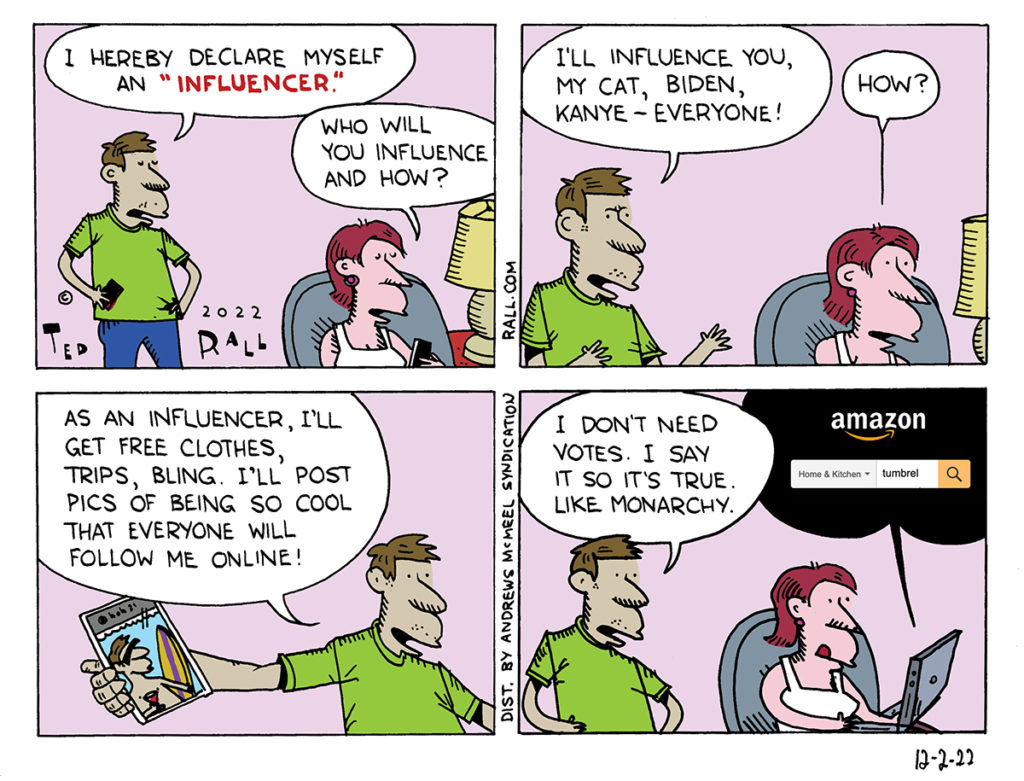

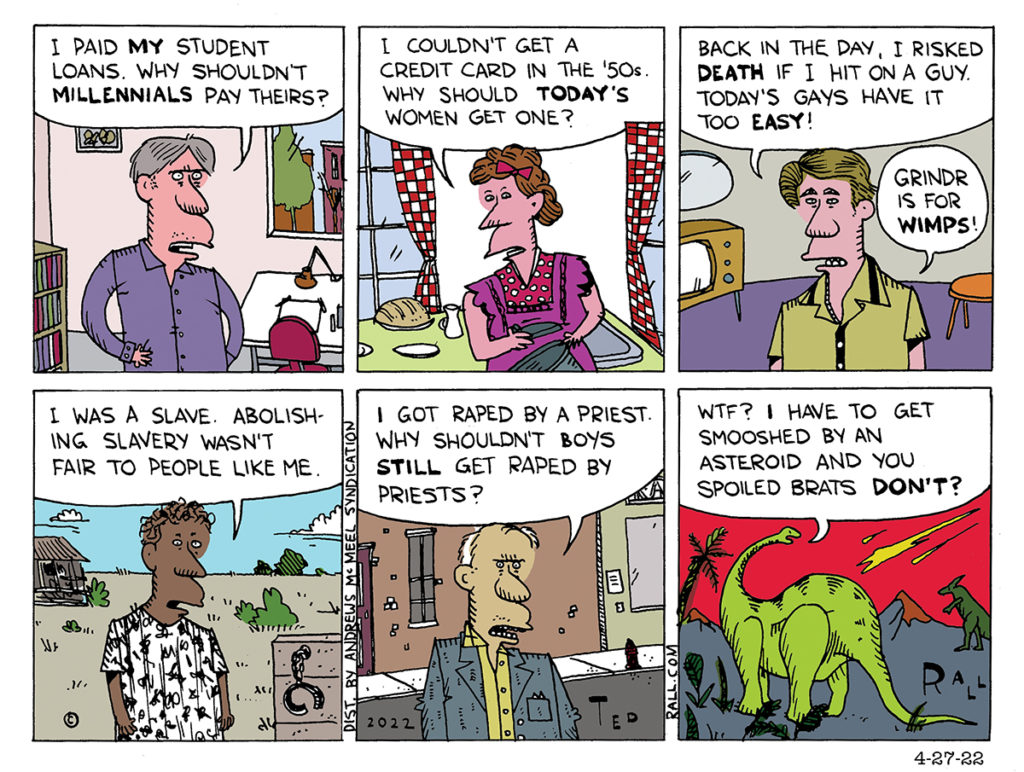

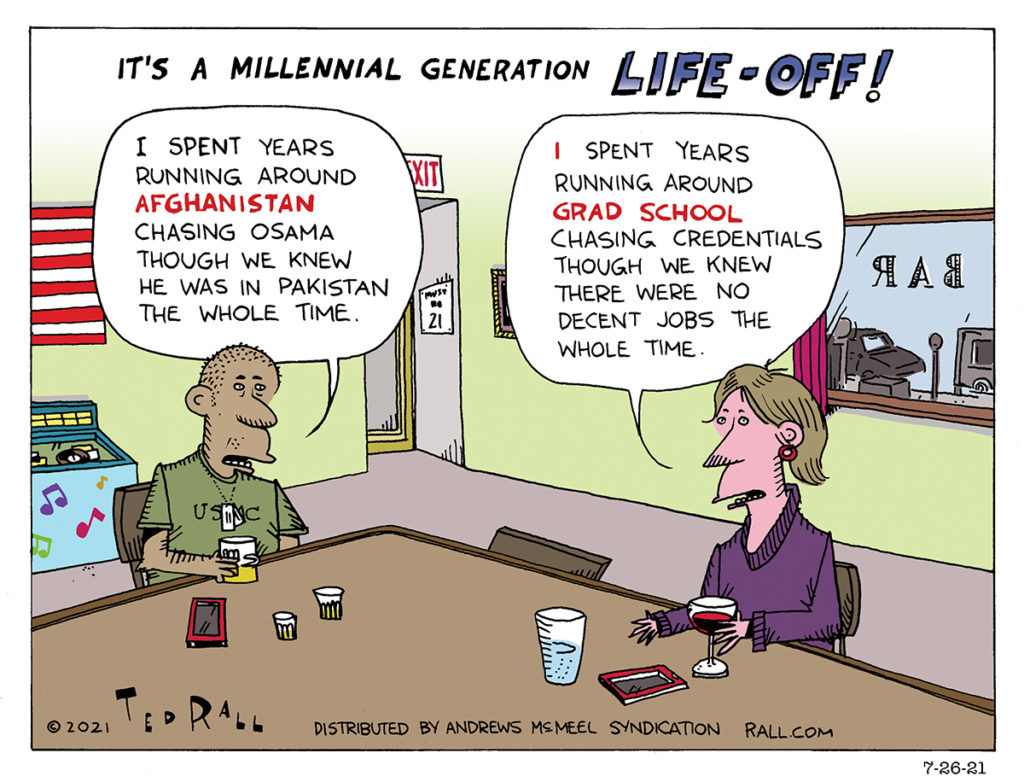

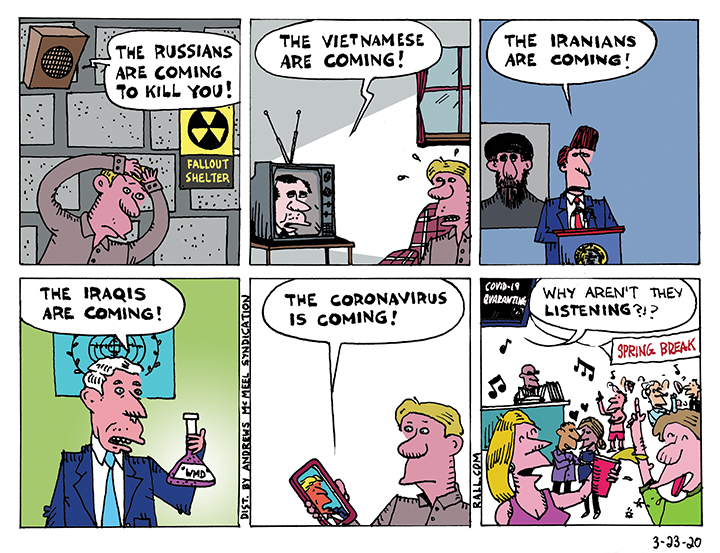

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis and The TMI Show with political analyst Manila Chan. His latest book, brand-new right now, is the graphic novel 2024: Revisited.)