A sinister transformation results in…nothing at all.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: United We Bland

Calls for a return to post-9/11 “unity” in the US, flirt with the elementary constructs of fascism, author says.

In the days and weeks after 9/11 the slogan was everywhere: T-shirts, bumper stickers, billboards that previously read “Your Ad Here” due to the dot-com crash, inevitably next to an image of the American flag.

The phrase carried with it a dark subtext. It wasn’t subtle:

United We Stand —or else.

Or, as George W. Bush, not known for his light rhetorical touch, put it: “You’re either with us or against us.”

“Us” was not meant to be inclusive. Le Figaro’s famous “nous sommes tous américains” headline aside, non-Americans were derided on Fox News (the Bush Administration’s house media organ) as “cheese-eating surrender monkeys.” (Never mind that that phrase, from the TV show “The Simpsons,” was conceived as derisive satire of the Right, which frequently derided the French as intellectual and thus weak and effete.)

Many Americans were disinvited from the “us” party of the early 2000s. Democrats, liberals, progressives, anyone who questioned Bush or his policies risked being smeared by Fox, right-wing talk radio hosts and their allies. The Wall Street Journal editorial page, for example, called me “the most anti-American cartoonist in America.”

For a day or two after the attacks on New York and Washington, it was possible even for the most jaundiced leftist to take comfort in patriotism. We were shocked. More than that, we were puzzled. No group had claimed responsibility. (None ever did.) Who was the enemy? Sure, there was conjecture. But no facts. What did “they” want?

“We watched, stupefied—it was immediately a television event in real time—and we were bewildered; no one had the slightest idea of why it had happened or what was to come,” writes Paul Theroux in the UK Telegraph. “It was a day scorched by death—flames, screams, sirens, confusion, fear and extravagant rumors (‘The Golden Gate Bridge has been hit, Seattle is bracing’).”

Politically, the nation reminded deeply divided by the disputed 2000 election. According to polls most voters believed that Bush was illegitimate, that he had stolen the presidential election in a judicial coup carried out by the Supreme Court. Even at the peak of Bush’s popularity in November 2001—89 percent of the public approved of his performance—47 percent of respondents to the Gallup survey said that Bush had not won fair and square. During those initial hours, however, most ordinary citizens saw 9/11 as a great horrible problem to be investigated, analyzed and then solved. Flags popped up everywhere. Even liberal Democrats gussied up their rides to make their cars look like a general’s staff car.

Dick Cheney and his cadre of high-level fanatics at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue were salivating over newly-drawn-up war plans. “There just aren’t enough targets in Afghanistan,” Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld told Cheney and Secretary of State Colin Powell. “We need to bomb something else to prove that we’re, you know, big and strong and not going to be pushed around.”

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: The US’ War of Words Against Syria

The US war of words against Syria is marred by hypocrisy and a lack of realism.

You’d need a team of linguists to tease out the internal contradictions, brazen hypocrisies and verbal contortions in President Barack Obama’s call for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to relinquish power.

“The future of Syria must be determined by its people, but…”

The “but” belies the preceding phrase—particularly since its speaker controls the ability and possible willingness to enforce his desires at the point of a depleted uranium warhead.

“The future of Syria must be determined by its people, but President Bashar al-Assad is standing in their way. His calls for dialogue and reform have rung hollow while he is imprisoning, torturing and slaughtering his own people,” Obama continued. One might say the same thing of Obama’s own calls for dialogue and reform in Iraq and Afghanistan. Except, perhaps, for the fact that the Iraqis and Afghans being killed are not Obama’s “own people”. As you no doubt remember from Bush’s statements about Saddam Hussein, American leaders keep returning to that phrase: “killing his own people”.

Now the Euros are doing it. “Our three countries believe that President Assad, who is resorting to brutal military force against his own people and who is responsible for the situation, has lost all legitimacy and can no longer claim to lead the country,” British Prime Minister David Cameron, French President Nicolas Sarkozy and German Chancellor Angela Merkel said in a joint statement.

If you think about this phrase, it doesn’t make sense. Who are “your” own people? Was Hitler exempt because he didn’t consider his victims to be “his” people? Surely Saddam shed few tears for those gassed Kurds. Anyway, it must have focus-grouped well back in 2002.

“We have consistently said that President Assad must lead a democratic transition or get out of the way,” Obama went on. “He has not led. For the sake of the Syrian people, the time has come for President Assad to step aside.” Here is US foreign policy summed up in 39 words: demanding the improbable and the impossible, followed by the arrogant presumption that the president of the United States has the right to demand regime change in a nation other than the United States.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: Tied to a Drowning Man

The interconnectedness of the world economy means that US economic woes will have severe effects on others.

During the Tajik Civil War of the late 1990s soldiers loyal to the central government found an ingeniously simple way to conserve bullets while massacring members of the Taliban-trained opposition movement. They tied their victims together with rope and chucked them into the Pyanj, the river that marks the border with Afghanistan. “As long as one of them couldn’t swim,” explained a survivor of that forgotten hangover of the Soviet collapse as he walked me to one of the promontories used for this act of genocide, “they all died.”

Such is the state of today’s integrated global economy.

Interdependence, liberal economists believe, furthers peace—a sort of economic mutual assured destruction. If China or the United States were to attack the other, the attacker would suffer grave consequences. But as the U.S. economy deteriorates from the Lost Decade of the 2000s through the post-2008 meltdown into what is increasingly looking like Marx’s classic crisis of late-stage capitalism, internationalization looks more like a suicide pact.

Like those Tajiks whose fates were linked by tightly-tied lengths of cheap rope, Europe, China and most of the rest of the world are bound to the United States—a nation that seems both unable to swim and unwilling to learn.

The collapse of the Soviet Union, a process that began in the 1970s and culminated with dissolution in 1991, had wide-ranging international implications. Russia became a mafia-run narco-state; millions perished of famine. Weakened Russian control of Central Asia, especially Afghanistan, set the stage for an emboldened and highly organized radical Islamist movement. Not least, it left the United States as the world’s last remaining superpower.

From an economic perspective, however, the effects were basically neutral. Coupled with its reliance on state-owned manufacturing industries to minimize dependence upon foreign trade, the USSR’s use of a closed currency ensured that other countries were not significantly impacted when the ruble went into a tailspin.

Partly due to its wild deficit spending on the gigantic military infrastructure it claimed was necessary to fight the Cold War—and then, after brief talk of a “peace dividend” during the 1990s, even more profligacy on the Global War on Terror—now the United States is, like the Soviet Union before it, staring down the barrel of economic apocalypse.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: How the US Media Marginalizes Dissent

The US media derides views outside of the mainstream as ‘un-serious’, and our democracy suffers as a result.

“Over the past few weeks, Washington has seemed dysfunctional,” conservative columnist David Brooks opined recently in The New York Times. “Public disgust [about the debt ceiling crisis] has risen to epic levels. Yet through all this, serious people—Barack Obama, John Boehner, the members of the Gang of Six—have soldiered on.”

Here’s some of what Peter Coy of Business Week magazine had to say about the same issue: “There is a comforting story about the debt ceiling that goes like this: Back in the 1990s, the U.S. was shrinking its national debt at a rapid pace. Serious people actually worried about dislocations from having too little government debt…”

Fox News, the Murdoch-owned house organ of America’s official right-wing, asserted: “No one seriously thinks that the U.S. will not honor its obligations, whatever happens with the current impasse on President Obama’s requested increase to the government’s $14.3 trillion borrowing limit.”

“Serious people.”

“No one seriously thinks.”

The American media deploys a deep and varied arsenal of rhetorical devices in order to marginalize opinions, people and organizations as “outside the mainstream” and therefore not worth listening to. For the most part the people and groups being declaimed belong to the political Left. To take one example, the Green Party—well-organized in all 50 states—is never quoted in newspapers or invited to send a representative to television programs that purport to present “both sides” of a political issue. (In the United States, “both sides” means the back-and-forth between center-right Democrats and rightist Republicans.)

Marginalization is the intentional decision to exclude a voice in order to prevent a “dangerous” opinion from gaining currency, to block a politician or movement from becoming more powerful, or both. In 2000 the media-backed consortium that sponsored the presidential debate between Vice President Al Gore and Texas Governor George W. Bush banned Green Party candidate Ralph Nader from participating. Security goons even threatened to arrest him when he showed up with a ticket and asked to be seated in the audience. Nader is a liberal consumer advocate who became famous in the U.S. for stridently advocating for safety regulations, particularly on automobiles.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: Censorship of Civilian Casualties in the US

US mainstream media and the public’s willful ignorance is to blame for lack of knowledge about true cost of wars.

Why is it so easy for American political leaders to convince ordinary citizens to support war? How is that, after that initial enthusiasm has given away to fatigue and disgust, the reaction is mere disinterest rather than righteous rage? Even when the reasons given for taking the U.S. to war prove to have been not only wrong, but brazenly fraudulent—as in Iraq, which hadn’t possessed chemical weapons since 1991—no one is called to account.

The United States claims to be a shining beacon of democracy to the world. And many of the citizens of the world believes it. But democracy is about responsiveness and accountability—the responsiveness of political leaders to an engaged and informed electorate, which holds that leadership class accountable for its mistakes and misdeeds. How to explain Americans’ acquiescence in the face of political leaders who repeatedly lead it into illegal, geopolitically disastrous and economically devastating wars of choice?

The dynamics of U.S. public opinion have changed dramatically since the 1960s, when popular opposition to the Vietnam War coalesced into an antiestablishmentarian political and culture movement that nearly toppled the government and led to a series of sweeping social reforms whose contemporary ripples include the recent move to legalize marriage between members of the same sex.

Why the difference?

Numerous explanations have been offered for the vanishing of protesters from the streets of American cities. First and foremost, fewer people know someone who has gotten killed. The death rate for U.S. troops has fallen dramatically, from 58,000 in Vietnam to a total of 6,000 for Iraq and Afghanistan. Many point to the replacement of conscripts by volunteer soldiers, many of whom originate from the working class, which is by definition less influential. Congressman Charles Rangel, who represents the predominantly African-American neighborhood of Harlem in New York, is the chief political proponent of this theory. He has proposed legislation to restore the military draft, which ended in the 1970s, four times since 9/11. “The test for Congress, particularly for those members who support the war, is to require all who enjoy the benefits of our democracy to contribute to the defense of the country. All of America’s children should share the risk of being placed in harm’s way. The reason is that so few families have a stake in the war which is being fought by other people’s children,” Rangel said in March 2011.

War is extraordinarily costly in cash as well as in lives. By 2009 the cost of invading and occupying Iraq had exceeded $1 trillion. During the 1960s and early 1970s conservatives unmoved by the human toll in Vietnam were appalled by the cost to taxpayers. “The myth that capitalism thrives on war has never been more fallacious,” argued Time magazine on July 13, 1970. Bear in mind, Time leaned to the far right editorially. “While the Nixon Administration battles war-induced inflation, corporate profits are tumbling and unemployment runs high. Urgent civilian needs are being shunted aside to satisfy the demands of military budgets. Businessmen are virtually unanimous in their conviction that peace would be bullish, and they were generally cheered by last week’s withdrawal from Cambodia.”

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: The Emperor Has No Economy

Corporate Profits Up, Consumer Income Down, Orwellian Talking Points Soar

The Associated Press’ Paul Wiseman had one of the snappier headlines last week: “The Economic Recovery Turns Two—Feel Better?”

“After previous recessions, people in all income groups tended to benefit,” Wiseman wrote. “This time, ordinary Americans are struggling with job insecurity, too much debt and pay raises that haven’t kept up with prices at the grocery store and gas station. The economy’s meager gains are going mostly to the wealthiest…A big chunk of the economy’s gains has gone to investors in the form of higher corporate profits.”

Wiseman quoted David Rosenberg, chief economist at Gluskin Sheff + Associates in Toronto: “The spoils have really gone to capital, to the shareholders.”

Karl Marx, call your office.

More than at any previous time in their lives, Americans looking for answers and facts are forced to read between the lines of press and broadcast accounts that bear little resemblance to reality “on the ground,” as they say on cable news. Truth, when it can be coaxed out of propaganda so patently ridiculous that it has become indiscernible from the standard-issue “everything is great, our leaders know best” nonsense of the world’s autocracies, is revealed in sloppy contradictions. Wiseman, though flying on the side of the agenda-busting angels, is no exception: is the U.S. economy generated “meager gains” or “spoils”? Hm.

On its face the official narrative is false to a laughably Orwellian extreme. The recession is over; the recovery is well underway, they say. However, as The Wall Street Journal reports, the recovery is slow and mainly benefiting big business. “While the U.S. economy staggers through one of its slowest recoveries since the Great Recession,” the paper wrote July 5th, “American companies are poised to report strong earnings for the second quarter—exposing a dichotomy between corporate performance and the overall health of the economy.”

The same “dichotomy” afflicts every industrialized nation except for Germany and Luxembourg, both of which have seen unemployment return to the levels before the global fiscal crisis that began in September 2008.

Logical holes in the argument gape so wide you could drive a truck through it—if it was worth putting it out on the road without goods to fill it with, or consumers to buy them.

First, high bottom lines don’t necessarily reflect healthy companies. A company can suffer declining sales and market share yet still increase profits by laying off workers, thus reducing payroll expenses. For example, the Internet search giant Yahoo! saw revenues decline 12 percent in late 2010 yet doubled its profits. How’d they do it? They fired one percent of their workforce. If Yahoo! were to continue this trend, it would soon cease to exist.

Second, First World economies are two-thirds reliant on consumer spending. Consumers in the United States, as well as those throughout the world, are in big trouble. The official U.S. unemployment rate is 9.1 percent but the “real rate”—the one calculated the way most other countries do theirs, which includes people whose unemployment benefits have lapsed—is closer to 20 percent, higher than those of Tunisia and Egypt at the start of the Arab Spring. People who still have jobs have suffered pay cuts both visible and invisible, the latter from galloping inflation in fuel and other costs that government agencies intentionally omit from calculations of consumer price indices.

Question one: Can an economy “recover” without its people?

Airports and shopping malls throughout the United States are empty. Advertising space on billboards and newspapers go begging. Storefronts from Fifth Avenue in New York to the Las Vegas Strip to small towns in the Midwest are boarded up. The price of homes, which for middle-class Americans are often their sole substantial form of savings, continues to decline after the real estate bubble burst in 2008. Consumer confidence, the measure of people’s willingness to part with cash to buy goods and services, is in the tank.

When 60 percent of Americans rate the economy as poor, don’t count on them to buy stuff.

They’re not.

“Workers’ wages and benefits [now] make up 57.5 percent of the economy, an all-time low,” wrote the AP’s Wiseman. “Until the mid-2000s, that figure had been remarkably stable—about 64 percent through boom and bust alike.”

Corporate CEOs may be whistling past the graveyard, raking in huge bonuses and pay raises approved by compliant boards of directors, but the overall state of the economy is a disaster. Recovery? Forget it—there isn’t one. Are we still in a recession? That would be an improvement. By most measures—unemployment, collapsing gross domestic product, falling incomes—this is a global depression. But the government won’t even admit that there’s a problem—except for unemployment and falling wages.

“Who are you going to believe?” the comedian Groucho Marx asked. ” Me, or your lying eyes?”

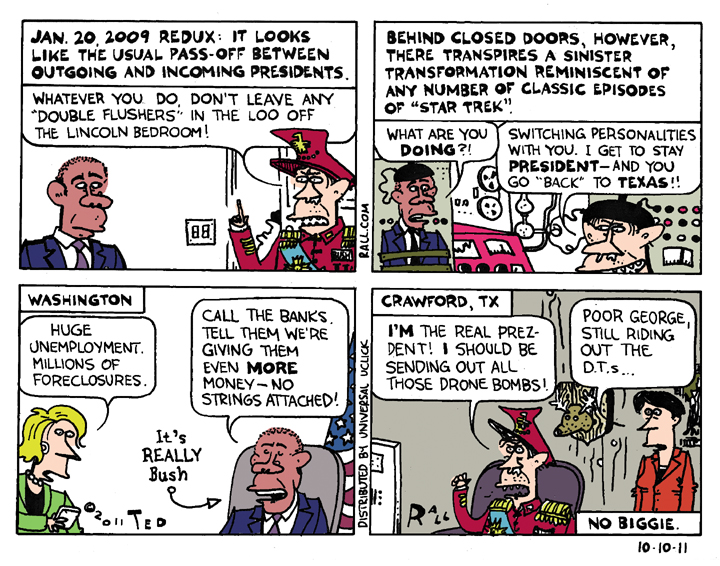

In the role of Mr. Marx is one Barack Obama. Like his outgoing predecessor George W. Bush, Obama’s response to the 2008 meltdown was to transfer trillions of dollars out of the U.S. treasury into the portfolios of investment banks, insurance companies, airlines and automobile manufacturers, no questions asked. This corporate-based approach relied upon Reagan-style trickle-down economics, the repeatedly failed theory that wealth transferred to the highest echelons of the ruling classes eventually “trickles down” in the form of increased spending, economic activity and hiring to the middle- and working classes. Not surprisingly, this non-response response succeeded in one area: increasing the salaries and perks of corporate executives. Job growth has been non-existent.

When Bush’s invading armies failed to find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, his administration’s answer was to claim that, in fact, they had. Obama’s economic strategy takes the same tack, repeatedly “talking up” the economy despite the hard evidence right before his listeners—in their paychecks or lack thereof—that there is little to brag about. Back in April 2009, Obama claimed that his pseudo-stimulus banker-enrichment program was “starting to generate signs of economic progress.”

The president stayed the course in 2010. “Make no mistake, we are headed in the right direction,” Obama said in July, while allowing: “We are not headed there fast enough for a lot of Americans. We’re not headed there fast enough for me either.”

January 2011: “We know these numbers can bounce around from month to month, but the trend is clear…The economy added 1.3 million jobs last year, and each quarter was stronger than the previous quarter, which means that the pace of hiring is beginning to pick up.”

Obama omitted the fact that the U.S. economy must add a net of 1.2 million jobs annually just to keep up with the increasing size of the labor force due to immigration and population growth.

June 2011: “There will be bumps on the road to recovery.”

Question two: What happens when you try to convince people who are suffering that, in fact, they are just fine?

Either Obama’s powers of persuasion are lacking or the American people have wised up. Whatever the reason, they don’t believe him. According to the Gallup poll, which asks whether respondents think the economy is improving or getting worse, the mood has become increasingly pessimistic along the bumpy road to recovery.

The Department of Labor announced this week that the U.S. economy had added a mere 18,000 jobs in June, a net loss of 82,000. Eight million jobs were lost during the 2008-09 debacle; some two to three million more since the “recovery” began.

The respected website Shadow Government Statistics currently places the real unemployment rate at 22.8 percent—equivalent to the worst months of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

With nearly one out of four Americans jobless and countless more underemployed, tensions are emerging between classes in this traditionally “classless” society in which both the rich and poor identify themselves as “middle class.” Though the wealthy always do better during tough times (well, during any times!), the gap is widening at an astonishing rate. “U.S. workers averaged $46,742 in 2010, up 2.6 percent from 2009,” according to USA Today. Bear in mind, with a real inflation rate (calculated the same way as inflation is calculated by other Western countries) of 11.2 percent, these workers are losing ground. Meanwhile, the paper noted, “average compensation among S&P 500 CEOs rose to $12 million in 2010, up 18 percent from 2009—and that’s not counting the potential multimillion-dollar value of stock or stock options, which are granted at set prices and provide holders profits as stock values rise.”

The numbers are jaw-dropping. John Hammergren, CEO of the McKesson healthcare services firm, received $150.7 million in 2010. Fashion maven Ralph Lauren paid himself $75.2 million. “Some of the gains are humongous,” said Paul Hodgson of GovernanceMetrics.

To the citizens of countries for whom $46,000 a year would seem like a king’s ransom, Americans’ resentment of CEOs who receive annual salaries on par with the gross domestic products of some nations no doubt seems petty if not a little silly. Yet they (and the CEOs) should ignore the prosperity chasm at their own peril. American politics, already more divisive as seen through such phenomena as the nativist Tea Party movement on the far right and the anarcho-libertarians of the left, will fracture further until the center (what center?) no longer holds.

Americans may be better off than most people on the planet. But they don’t feel like it. Perception becomes reality when people are scared.

The world cannot feel safe when its sole remaining superpower is falling apart at the seams. If patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel, militarism is the desperate last act of an oppressive government in a state of economic collapse.

At the core of the when-is-a-recovery-not-a-recovery question is vocabulary. What is a recession? How do we know when it’s over?

Beginning in the 1970s American economists began to define recession as being in effect when GDP falls during two consecutive fiscal quarters.

One result of this definition is that a recession is often not officially “declared” by mainstream economists until it is over—i.e., when GDP begins to rise again. This contributes to a strange reality gap: We are not in a recession until we are in a recovery. Effectively, then, it is rare for the American news media to state at any given time that the U.S. economy is then in a recession. Naturally, this contributes to the perception that newspapers and TV stations lie to them, and that they do so on behalf of an uncaring regime.

The 2008 collapse was exceptionally long. Nevertheless, this rule of the undeclared recession held. On December 1, 2008 the National Bureau of Economic Research declared that a recession head begun on December 1, 2007. They later declared it over as of June 2009. Thus a recession that had lasted one and a half years was only officially acknowledged for six months.

Moreover, the definition of recession is obviously faulty.

For most ordinary people, unemployment is the leading economic indicator. A secondary indicator is income.

Do I have a job?

Can I find a job?

How much can I earn?

The answers to those questions provide the most accurate indicators of economic health. When two-thirds of the economy (or 59 percent now) relies on consumer spending, who gives two figs about whether GDP goes up or down during two consecutive quarters? The fact that the press takes this non-people-based definition of recession seriously provides strong insight into its mindset: People are irrelevant.

“The average American does not view the economy through the prism of GDP or unemployment rates or even monthly jobs numbers,” top presidential advisor David Plouffe says, nearly sounding human. “People won’t vote based on the unemployment rate. They’re going to vote based on: ‘How do I feel about my own situation? Do I believe the president makes decisions based on me and my family?'”

Based on that assessment, Obama should start packing. He has not done anything that might have helped the unemployed: extending jobless benefits, forcing banks to renegotiate mortgages for homeowners, imposing national commercial and residential rent control, substantial tax credits for the poor and working class. And it shows: the consumer who lays the golden egg has no money to spend—and economic activity has all but ceased.

People are furious. But they are angrier at the thought that the rich are getting richer and that the president isn’t actively searching for solutions than they are about the fact that they can’t pay their bills.

Two years into Obama’s presidency “we are still treading water at the bottom of a deep hole,” summarizes economist Heidi Shierholz.

In the not-so-long run, however, things could get a lot uglier than the Democrats taking a beating in America’s November 2012 elections. The R-word—not recession, but revolution—could be in the offing.

Ted Rall is an American political cartoonist, columnist and author. His most recent book is The Anti-American Manifesto. His website is rall.com.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: Too Soon To Tell

I am pleased to announce that I am now writing a weekly long-form column for Al Jazeera English. Here is my second piece for Al Jazeera:

One Year Early, Obama’s Reelection Far From Certain

The American punditocracy (and, perhaps more importantly, Las Vegas oddsmakers) currently cite Barack Obama as their odds-on favorite to win next year’s presidential election. Some even predict a landslide.

Mainstream media politicos acknowledge the atrocious economy, with its real unemployment rate nearly matching the worst years of the Great Depression of the 1930s, as an obstacle to reelection. But most of them believe that other factors will prove decisive: disarray in the field of candidates for the nomination of the opposition Republican Party, the GOP’s reliance on discredited Reagan-style austerity measures for the masses coupled with tax cuts for the wealthy, and Obama’s assassination of Osama bin Laden.

Maybe they’re right. But if I were the President, I wouldn’t be offering the White House chef a contract renewal any time soon. Count me among the majority of Americans (54 to 44 percent) who told a March 2011 CNN/Opinion Research poll they think Obama will lose the 2012 election.

I could be wrong.

Scott Keeter, director of survey research at the Pew Research Center, doesn’t think much of these so-called “trial-run” polls. “A review of polls conducted in the first quarter of the year preceding the election found many of them forecasting the wrong winner—often by substantial margins,” Keeter wrote in 2007, citing three elections as far back as 1968.

However, a historical analysis of the more recent presidential races, those over the two decades, reveals an even bigger gap. The year before a U.S. presidential election, the conventional wisdom is almost always wrong. The early favorite at this point on the calendar usually loses. So betting against the pundits—in this case, against Obama—is the safe bet at this point.

The meta question is: what difference does it make who wins next year? In practical terms, not much.

For one thing, American presidents tend to find more heartbreak than political success during their second terms. Had Richard Nixon retired in 1972, for example, he would have been fondly remembered as the architect of the Paris peace talks that ended the Vietnam War, the founder of the Environmental Protection Agency, and the defender of the working and middle class (for imposing wage and price controls to soften the effect of inflation). His second term saw him sinking into, and ultimately succumbing, to the morass of the Watergate scandal.

The next second termer, Ronald Reagan, was similarly preoccupied by scandal, in case the Iran-Contra imbroglio in which the United States traded arms to Iran in return for hostages held by students in Tehran and illegally funded right-wing death squads in Central America. Bill Clinton’s last four years were overshadowed by his developing romance, and the consequences of the revelation thereof, with intern Monica Lewinsky. George W. Bush’s second term, from 2005 to 2009, was defined by his administration’s inept response to hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, the deteriorating security situation in U.S.-occupied Afghanistan and Iraq, and the economic collapse that began in 2008. His number-one political priority, privatizing the U.S. Social Security system, never got off the ground.

Presidents rarely accomplish much of significance during their second term. So why do they bother to run again? Good question. Whether it’s ego—1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is one hell of an address—or something else, I don’t know. Whatever, I have long maintained that a sane president would think of himself as standing for one four-year term, then announce his intention not to run again at the last possible moment.

From the standpoint of the American people and the citizens of countries directly affected by U.S. foreign policy, it is unlikely that the basic nature of the beast will change much regardless of Obama’s fortunes in the next election. One only has to consider the subtle “differences” between the tenures of Presidents Bush and Obama.

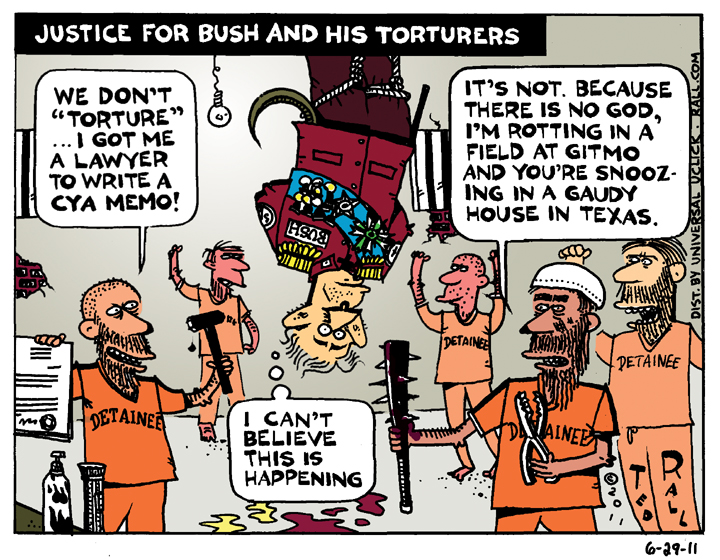

On the domestic front Obama continued and expanded upon Bush’s non-reaction to the economic crisis, exploiting the panic created by widespread unemployment, the bursting of the housing bubble and a massive foreclosure crisis that put tens of millions of Americans out of their homes in order to pour hundreds of billions of federal dollars into the pockets of the top executives of the nation’s largest banks, with no resulting stimulus effect whatsoever. Controversial attacks on privacy rights and civil liberties inaugurated by the Bush years were expanded and extended: the USA-Patriot Act, the National Security Agency “domestic surveillance” program that allowed the government to spy on U.S. citizens’ phone calls, emails and other communications. Obama even formalized Bush’s assertion that the president has the right to unilaterally order the assassination of anyone, including a U.S. citizen, without evidence or proof that he or she has committed a crime.

As promised during the 2008 campaign, Obama expanded the U.S. war against Afghanistan, transforming what Bush described as a short-term attempt to find Osama bin Laden after 9/11 into the most protracted military conflict in the history of the United States. The war continued in Iraq, albeit with “combat” troops redefined as “trainers.” During the last few years, the “global war on terror” expanded into Pakistan, east Africa, Libya and Yemen. Drone attacks escalated. Violating his campaign promises, he continued to keep torture available as a legal option—indeed, he ordered it against a U.S. solder, Private First Class Bradley Manning—and kept Guantánamo and other Bush-era concentration camps open.

If Obama goes down to defeat next year, then, the results should be viewed less as a shift in overall U.S. policy—hegemonic, imperialistic, increasingly authoritarian—than one that is symbolic. An Obama defeat would reflect the anger of ordinary Americans caught in the “two-party trap,” flailing back and forth between the Dems and the Reps, voting against the party in power to express their impotent rage, particularly at the economy. Mr. Hopey-Changey’s trip back to Chicago would mark the end of a brief, giddy, moment of reformism.

The argument that an overextended, indebted empire can be repaired via internal changes of personnel would be dead. With the reformism that Obama embodied no longer politically viable, American voters would be once again faced, as are the citizens of other repressive states, with the choice between sullen apathy and revolution.

Obamaism is currently believed to be unstoppable. If history serves as an accurate predictor, that belief is good cause to predict its defeat next November.

During the late spring and early summer of 1991, just over a year before the 1992 election, President George H.W. Bush was soaring in the polls in the aftermath of the Persian Gulf War, which the American media positively portrayed as successful, quick, internationalist, and cost the lives of few America soldiers. A March 1991 CBS poll gave him an 88 percent approval rating—a record high.

By October 1991 Bush was heavily favored to win. A Pew Research poll found that 78 percent of Democratic voters thought Bush would defeat any Democratic nominee. New York governor Mario Cuomo, an eloquent, charismatic liberal star of the party, sized up 1992 as unwinnable and decided not to run.

When the votes were counted, however, Democrat Bill Clinton defeated Bush, 43 to 37.5 percent. Although Republicans blamed insurgent billionaire Ross Perot’s independent candidacy for siphoning away votes from Bush, subsequent analyses do not bear this out. In fact, Perot’s appeal had been bipartisan, attracting liberals opposed to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the U.S., Canada and Mexico and globalization in general, as well as conservative deficit hawks.

The most credible explanation for Bush’s defeat was handwritten on a sign that the victorious Bill Clinton’s campaign manager famously taped to the wall of the Dems’ war room: “It’s the economy, stupid.” As the 1989-1993 recession deepened Bush’s ratings tumbled to around 30 percent. A February 1992 incident, in which Bush was depicted by The New York Times as wearing “a look of wonder” when confronted with a supermarket price scanning machine, solidified his reputation with voters as patrician, out of touch, and unwilling to act to stimulate the economy or alleviate the suffering of the under- and unemployed. “Exit polls,” considered exceptionally reliable because they query voters seconds after exiting balloting places, showed that 75 percent of Americans thought the economy was “bad” or “very bad.”

In 1995, Bill Clinton was preparing his reelection bid. On the Republican side, Kansas senator and 1976 vice presidential candidate Bob Dole was expected to (and did) win his party’s nomination. Perot ran again, but suffered from a media blackout; newspapers and broadcast outlets had lost interest in him after a bizarre meltdown during the 1992 race in which he accused unnamed conspirators of plotting to violently disrupt his daughter’s wedding. He received eight percent in 1996.

Clinton trounced Dole, 49 to 40 percent. In 1995, however, that outcome was anything but certain. Bill Clinton had been severely wounded by a series of missteps during his first two years in office. His first major policy proposal, to allow gays and lesbians to serve openly in the U.S. military, was so unpopular that he was forced to water it down into the current “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” compromise. Clinton’s 1993 attempt to deprivatize the healthcare system, mocked as HillaryCare after he put his wife in charge of marketing it, went down to defeat. He signed the pro-corporate, Republican-backed trade agreement, NAFTA, alienating his party’s liberal and progressive base. Low voter turnout by the American left in the 1994 midterm elections led to the “Republican Revolution,” a historic sweep of both houses of the American Congress by right-wing conservatives led by the fiery new Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich.

1995 saw the so-called “co-presidency” between Gingrich and a cowed Bill Clinton, who was reduced to telling a press conference that “the president is relevant.” The United States, which does not have a European-style parliamentary system, had never seen a president so politically weak while remaining in office.

During the spring and summer of 1995 Bob Dole was already the heir apparent to the nomination of a Republican Party that traditionally rewards those who wait their turn. Dole was a seasoned campaigner, a Plains States centrist whose gentlemanly demeanor and credentials as a hero of World War II. Conventional wisdom had him beating Clinton. So did the polls. A March 1995 Los Angeles Times poll had Dole defeating Clinton, 52 to 44 percent in a head-to-head match-up. “Among all voters, Clinton’s generic reelect remains dismal, with 40 percent inclined to vote him in again and 53% tilting or definitely planning a vote against him,” reported the Times.

By late autumn, however, the polls had flipped. Though statisticians differ about how big a factor it was, a summer 1995 shutdown of the federal government blamed on the refusal of Gingrich’s hardline Republicans to approve the budget turned the tide. At the end of the year the die was cast. As Americans began to pay more attention to his challenger they recoiled at Dole’s age—if elected, he would have been the oldest president in history, even older than Reagan—as it contrasted with Clinton’s youthful vigor. The Democrat coasted to reelection. But that’s not how things looked at this stage in the game.

When analyzing the 2000 race, remember that Republican George W. Bush lost the election to Al Gore by a bizarre quirk of the American system, the Electoral College. The U.S. popular vote actually determines the outcome of elected delegates to the College from each of the 50 states. The winner of those delegates is elected president.

Most of the time, the same candidate wins the national popular vote and the Electoral College tally. In 2000, there is no dispute: Democrat Al Gore won the popular vote, 48.4 to 47.9 percent. There was a legal dispute over 25 electoral votes cast by the state of Florida; ultimately the U.S. Supreme Court decided, along party lines, to award the state to Bush despite clear indications that Gore would have won recounts by tens of thousands of votes in that state.

Regardless of one’s views of the 2000 Florida recount controversy, from a predictive standpoint, one should assume that Gore won because no one could have anticipated a difference between the results of the electoral and popular votes.

Under normal circumstances Gore should have faced, as Dick Cheney said about the Iraq invasion, a cakewalk. A popular sitting vice president, he enjoyed the trappings of incumbency and a reputation as a thoughtful environmentalist and government efficiency expert. The economy was booming—always a good argument for the “don’t change horses in midstream” sales pitch. The early favorite on the Republican side, George W. Bush, was considered an intellectual lightweight who would get eaten alive the first time the two met in a presidential debate. But Monicagate had wounded Bill Clinton to the extent that Gore made a fateful decision to disassociate himself from the president who had appointed him.

A January 1999 CNN poll had Bush over Gore, 49 to 46 percent. By June 2000 the same poll had barely budged: now it was 49 to 45 percent. “The results indicate that the public is far more likely to view Texas Governor George W. Bush as a strong and decisive leader, and is also more confident in Bush’s ability to handle an international crisis—a worrisome finding for a vice president with eight years of international policy experience,” analyzed CNN in one of the most frightening summaries of the American people’s poor judgment ever recorded.

Gore didn’t become president. But he won the 2000 election. Once again, the media was wrong.

In the 2004 election, it was my turn to screw up. Howard Dean, the combative liberal darling and former Vermont governor, was heavily favored to win the Democratic nomination against incumbent George W. Bush. I was so convinced at his inevitability after early primary elections and by the importance of unifying the Democratic Party behind a man who could defeat Bush that I authored a column I wish I could chuck down the memory hole calling for the party to suspend remaining primaries and back Dean. In 2004, John Kerry won the nomination.

Oops.

But I wasn’t alone. Polls and pundits agreed that George W. Bush, deeply embarrassed by the failure to find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, would lose to Kerry, a Democrat with a rare combination of credentials: he was a bonafide war hero during the Vietnam War and a noted opponent of the war after his service there.

Bush trounced Kerry. “How can 59,054,087 people be so DUMB?” asked Britain’s Daily Mirror. Good question. Maybe that’s why no one saw it coming.

Which brings us to the most recent presidential election. First, the pundit class was wrong about the likely Democratic nominee. Former First Lady and New York Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton, everyone “knew,” would win. It wasn’t even close. An August 2007 Gallup/USA Today poll had Clinton ahead of Obama, 48 to 26 percent. As it turned out, many Democratic primary voters were wowed by Obama’s charisma and annoyed by Clinton’s refusal to apologize for her brazenly cynical vote in favor of the Iraq war in 2003. Aging Arizona Senator John McCain, on the other hand, remained the best-funded, and thus the continuous favorite, on the Republican side.

Obama’s advantages over McCain became clear by 2008. “The political landscape overwhelmingly favors Obama,” reported USA Today in June. At this point in 2007?

He didn’t stand a chance.

Ted Rall is an American political cartoonist, columnist and author. His most recent book is The Anti-American Manifesto. His website is rall.com.

AL JAZEERA ENGLISH COLUMN: Obama’s Third War

Yesterday I published my first column for Al Jazeera English. I get more space than my syndicated column (2000 words compared to the usual 800) and it’s an exciting opportunity to run alongside a lot of other writers whose work I respect.

Here it is:

Stalemate in Libya, Made in USA

Republicans in the United States Senate held a hearing to discuss the progress of what has since become the war in Libya. It was one month into the operation. Senator John McCain, the Arizona conservative who lost the 2008 presidential race to Barack Obama, grilled top U.S. generals. “So right now we are facing the prospect of a stalemate?” McCain asked General Carter Ham, chief of America’s Africa Command. “I would agree with that at present on the ground,” Ham replied.

How would the effort to depose Colonel Gaddafi conclude? “I think it does not end militarily,” Ham predicted.

That was over two months ago.

It’s a familiar ritual. Once again a military operation marketed as inexpensive, short-lived and—naturally—altruistic, is dragging on, piling up bills, with no end in sight. The scope of the mission, narrowly defined initially, has radically expanded. The Libyan stalemate is threatening to become, along with Iraq and especially Afghanistan, America’s third quagmire.

Bear in mind, of course, that the American definition of a military quagmire does not square with the one in the dictionary, namely, a conflict from which one or both parties cannot disengage. The U.S. could pull out of Libya. But it won’t. Not yet.

Indeed, President Obama would improve his chances in his upcoming reelection campaign were he to order an immediate withdrawal from all four of America’s “hot wars”: Libya, along with Afghanistan, Iraq, and now Yemen. When the U.S. and NATO warplanes began dropping bombs on Libyan government troops and military targets in March, only 47 percent of Americans approved—relatively low for the start of a military action. With U.S. voters focused on the economy in general and joblessness in particular, this jingoistic nation’s typical predilection for foreign adventurism has given way to irritation to anything that distracts from efforts to reduce unemployment. Now a mere 26 percent support the war—a figure comparable to those for the Vietnam conflict at its nadir.

For Americans “quagmire” became a term of political art after Vietnam. It refers not to a conflict that one cannot quit—indeed, the U.S. has not fought a war where its own survival was at stake since 1815—but one that cannot be won. The longer such a war drags on, with no clear conclusion at hand, the more that American national pride (and corporate profits) are at stake. Like a commuter waiting for a late bus, the more time, dead soldiers and materiel has been squandered, the harder it is to throw up one’s hands and give up. So Obama will not call off his dogs—his NATO allies—regardless of the polls. Like a gambler on a losing streak, he will keep doubling down.

U.S. ground troops in Libya? Not yet. Probably never. But don’t rule them out. Obama hasn’t.

It is shocking, even by the standards of Pentagon warfare, how quickly “mission creep” has imposed itself in Libya. Americans, at war as long as they can remember, recognize the signs: more than half the electorate believes that U.S. forces will be engaged in combat in Libya at least through 2012.

One might rightly point out: this latest American incursion into Libya began recently, in March. Isn’t it premature to worry about a quagmire?

Not necessarily.

“Like an unwelcome specter from an unhappy past, the ominous word ‘quagmire’ has begun to haunt conversations among government officials and students of foreign policy, both here and abroad,” R.W. Apple, Jr. reported in The New York Times. He was talking about Afghanistan.

Apple was prescient. He wrote his story on October 31, 2001, three weeks into what has since become the United States’ longest war.

Obama never could have convinced a war-weary public to tolerate a third war in a Muslim country had he not promoted the early bombing campaign as a humanitarian effort to protect Libya’s eastern-based rebels (recast as “civilians”) from imminent Srebrenica-esque massacre by Gaddafi’s forces. “We knew that if we waited one more day, Benghazi—a city nearly the size of Charlotte [North Carolina]—could suffer a massacre that would have reverberated across the region and stained the conscience of the world,” the President said March 28th. “It was not in our national interest to let that happen. I refused to let that happen.”

Obama promised a “limited” role for the U.S. military, which would be part of “broad coalition” to “protect civilians, stop an advancing army, prevent a massacre, and establish a no-fly zone.” There would be no attempt to drive Gaddafi out of power. “Of course, there is no question that Libya—and the world—would be better off with Gaddafi out of power,” he said. “I, along with many other world leaders, have embraced that goal, and will actively pursue it through non-military means. But broadening our military mission to include regime change would be a mistake.”

“Regime change [in Iraq],” Obama reminded, “took eight years, thousands of American and Iraqi lives, and nearly a trillion dollars. That is not something we can afford to repeat in Libya.”

The specifics were fuzzy, critics complained. How would Libya retain its territorial integrity—a stated U.S. war aim—while allowing Gaddafi to keep control of the western provinces around Tripoli?

The answer, it turned out, was essentially a replay of Bill Clinton’s bombing campaign against Serbia during the 1990s. U.S. and NATO warplanes targeted Gaddafi’s troops. Bombs degraded Libyan military infrastructure: bases, radar towers, even ships. American policymakers hoped against hope that Gaddafi’s generals would turn against him, either assassinating him in a coup or forcing the Libyan strongman into exile.

If Gaddafi had disappeared, Obama’s goal would have been achieved: easy in, easy out. With a little luck, Islamist groups such as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb would have little to no influence on the incoming government to be created by the Libyan National Transitional Council. With more good fortune, the NTC could even be counted upon to sign over favorable oil concessions to American and European energy concerns.

But Gaddafi was no Milosevic. The dictator dug in his heels. This was at least in part due to NATO’s unwillingness or inability to offer him the dictator retirement plan of Swiss accounts, gym bags full of bullion, and a swanky home in the French Riviera.

Stalemate was the inevitable result of America’s one foot in, one foot out Libya war policy—an approach that continued after control of the operation was officially turned over to NATO, specifically Britain and France. Allied jets were directed to deter attacks on Benghazi and other NTC-held positions, not to win the revolution for them. NTC forces, untrained and poorly armed, were no match for Gaddafi’s professional army. On the other hand, loyalist forces were met by heavy NATO air strikes whenever they tried to advance into rebel-held territory. Libya was bifurcated. With Gaddafi still alive and in charge, this was the only way Obama Administration policy could have played out.

No one knows whether Gaddafi’s angry bluster—the rants that prompted Western officials to attack—would have materialized in the form of a massacre. It is clear, on the other hand, that Libyans on both sides of the front are paying a high price for the U.S.-created stalemate.

At least one million out of Libya’s population of six million has fled the nation or become internally displaced refugees. There are widespread shortages of basic goods, including food and fuel. According to the Pakistani newspaper Dawn, the NTC has pulled children out of schools in areas they administer and put them to work “cleaning streets, working as traffic cops and dishing up army rations to rebel soldiers.”

NATO jets fly one sortie after another; the fact that they’re running out of targets doesn’t stop them from dropping their payloads. Each bomb risks killing more of the civilians they are ostensibly protecting. Libyans will be living in rubble for years after the war ends.

Coalition pilots were given wide leeway in the definition of “command and control centers” that could be targeted; one air strike against the Libyan leader’s home killed 29-year-old Mussa Ibrahim said Saif al-Arab, Gaddafi’s son, along with three of his grandchildren. Gaddafi himself remained in hiding. Officially, however, NATO was not allowed to even think about trying to assassinate him.

Pentagon brass told Obama that more firepower was required to turn the tide in favor of the ragtag army of the Libyan National Transitional Council. But he couldn’t do that. He was faced with a full-scale rebellion by a coalition of liberal antiwar Democrats and Republican constitutionalists in the U.S. House of Representatives. Furious that the President had failed to request formal Congressional approval for the Libyan war within 60 days as required by the 1973 War Powers Resolution, they voted against a military appropriations bill for Libya.

The planes kept flying. But Congress’ reticence now leaves one way to close the deal: kill Gaddafi.

As recently as May 1st,, after the killing of Gaddafi’s son and grandchildren, NATO was still denying that it was trying to dispatch him. “We do not target individuals,” said Lieutenant General Charles Bouchard of Canada, commanding military operations in Libya.

By June 10th CNN television confirmed that NATO was targeting Libya’s Brother Leader for death. “Asked by CNN whether Gaddafi was being targeted,” the network reported, “[a high-ranking] NATO official declined to give a direct answer. The [UN] resolution applies to Gaddafi because, as head of the military, he is part of the control and command structure and therefore a legitimate target, the official said.”

In other words, a resolution specifically limiting the scope of the war to protecting civilians and eschewing regime change was being used to justify regime change via political assassination.

So what happens next?

First: war comes to Washington. On June 14th House of Representatives Speaker John Boehner sent Obama a rare warning letter complaining of “a refusal to acknowledge and respect the role of Congress” in the U.S. war against Libya and a “lack of clarity” about the mission.

“It would appear that in five days, the administration will be in violation of the War Powers Resolution unless it asks for and receives authorization from Congress or withdraws all U.S. troops and resources from the mission [in Libya],” Boehner wrote. “Have you…conducted the legal analysis to justify your position?” he asked. “Given the gravity of the constitutional and statutory questions involved, I request your answer by Friday, June 17, 2011.”

Next, the stalemate/quagmire continues. Britain can keep bombing Libya “as long as we choose to,” said General Sir David Richards, the UK Chief of Defense Staff.

One event could change everything overnight: Gaddafi’s death. Until then, NATO and the United States must accept the moral responsibility for dragging out a probable aborted uprising in eastern Libya into a protracted civil war with no military—or, contrary to NATO pronouncements, political—solution in the foreseeable future. Libya is assuming many of the characteristics of a proxy war such as Afghanistan during the 1980s, wherein outside powers armed warring factions to rough parity but not beyond, with the effect of extending the conflict at tremendous cost of life and treasure. This time around, only one side, the NTC rebels, are receiving foreign largess—but not enough to score a decisive victory against Gaddafi by capturing Tripoli.

Libya was Obama’s first true war. He aimed to show how Democrats manage international military efforts differently than neo-cons like Bush. He built an international coalition. He made the case on humanitarian grounds. He declared a short time span.

In three short months, all of Obama’s plans have fallen apart. NATO itself is fracturing. There is talk about dissolving it entirely. The Libya mission is stretching out into 2011 and beyond.

People all over the world are questioning American motives in Libya and criticizing the thin veneer of legality used to justify the bombings. “We strongly believe that the [UN] resolution [on Libya] is being abused for regime change, political assassinations and foreign military occupation,” South African President Jacob Zuma said this week, echoing criticism of the invasion of Iraq.

Somewhere in Texas, George W. Bush is smirking.

Ted Rall is an American political cartoonist, columnist and author. His most recent book is The Anti-American Manifesto. His website is rall.com.

(C) 2011 Ted Rall, All Rights Reserved.