LIVE 10 AM Eastern time, Streaming Anytime:

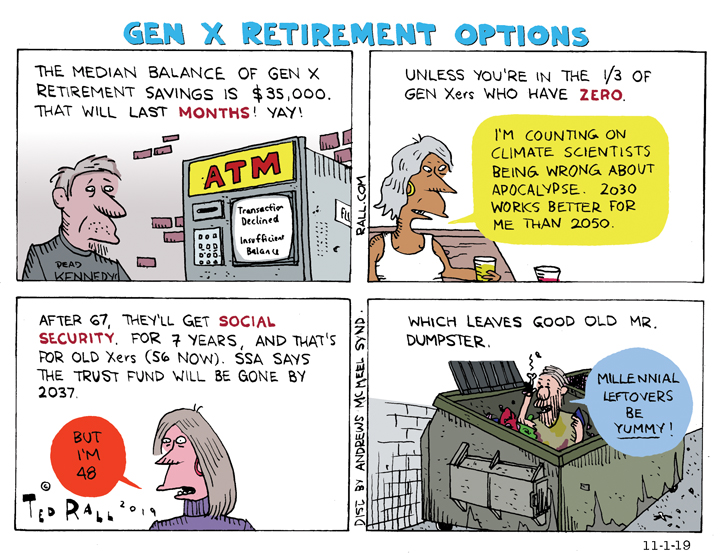

In 1996, “TMI Show” co-host Ted Rall wrote the bestselling Gen X manifesto Revenge of the Latchkey Kids. In that generational classic and countless gritty cartoons, Ted predicted that, no matter what age they were, Gen X would arrive at the worst time to be that age due to the phenomenon of “Generational Leapfrog”: the Baby Boomers would run the show and pass the torch over Gen X to the Boomers’ children, the Millennials.

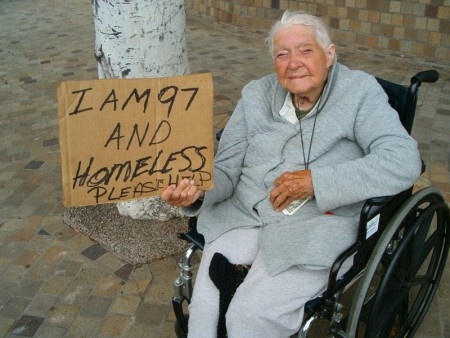

On “The TMI Show” with hosts Ted Rall and Manila Chan, we tell you just how true that has turned out to be. Gen Xers—born between 1961 and 1978—are now in their 40s, 50s, and even low 60s, and they’re supposed to be at the peak of their careers, Not quite. Ageism is rampant, job opportunities are drying up, and they’re caught in a brutal tug-of-war with Millennials, Gen Z, and Boomers who won’t retire. Layoffs in tech and media are hitting hard, leaving seasoned pros out in the cold.

Yet Gen X isn’t backing down. These former latchkey kids, who bridged the analog-to-digital revolution, are famous for their resilience and adaptability. Despite career plateaus and economic uncertainty throughout their lives, many are reinventing themselves, refusing to coast into retirement. From dodging coded rejections for being “overqualified” to battling the “sandwich” phase of supporting kids and aging parents, Gen Xers are going out kicking and screaming. Tune in for a real talk session with Ted—Gen X 1.0—and Manila—Gen X 2.0—exposing Millennials’ ageism and the multigenerational job competition. The TMI Show drops demographic truth bombs you won’t hear elsewhere.

Plus:

- El Señor Presidenté Para Siempre: El Salvador’s Congress, controlled by ruthless authoritarian despot Nayib Bukele, approves constitutional reforms allowing indefinite re-election and extending presidential terms to six years. Bukele, popular for reducing gang violence, now holds near-total institutional control, running a virtual dictatorship. Critics point to arrests of human rights defenders and his CECOT gulag as evidence of incipient fascism.

- Surrogacy Pedophile: Two gay men, including convicted child sex offender Brandon Keith Riley-Mitchell, raise a baby via surrogacy, bypassing adoption rules. Their viral crowdfunding campaign sparked outrage after Riley-Mitchell’s criminal history came out. The case exposes loopholes in surrogacy laws, with similar concerns raised in a Los Angeles child neglect case.

- More Bumpy Rides: Severe turbulence on a Delta flight from Salt Lake City to Amsterdam injures 25 passengers, forcing an emergency landing in Minnesota. Passengers describe chaotic scenes with items and people thrown about the cabin. Research links increasing turbulence to climate change; this is going to happen more often.

- Sacred Gems Come Home: India reclaims the sacred Piprahwa Gems, linked to the Buddha, after 127 years. Unearthed in 1898, the collection was nearly auctioned before a legal dispute led to its purchase by Godrej Industries. The gems will now be displayed permanently in India.

Like many other Americans this week, I have been impressed with the poise, passion and guts of the Florida teenagers who survived the latest big school shooting, as well as that of their student allies in other cities who walked out of class, took to the streets and/or confronted government officials to demand that they take meaningful action to reduce gun violence. As we mark a series of big 50th anniversaries of the cluster of dramatic events that took place in 1968, one wonders: does this augur a return to the street-level militancy of that tumultuous year?

Like many other Americans this week, I have been impressed with the poise, passion and guts of the Florida teenagers who survived the latest big school shooting, as well as that of their student allies in other cities who walked out of class, took to the streets and/or confronted government officials to demand that they take meaningful action to reduce gun violence. As we mark a series of big 50th anniversaries of the cluster of dramatic events that took place in 1968, one wonders: does this augur a return to the street-level militancy of that tumultuous year?