Originally published by ANewDomain.net:

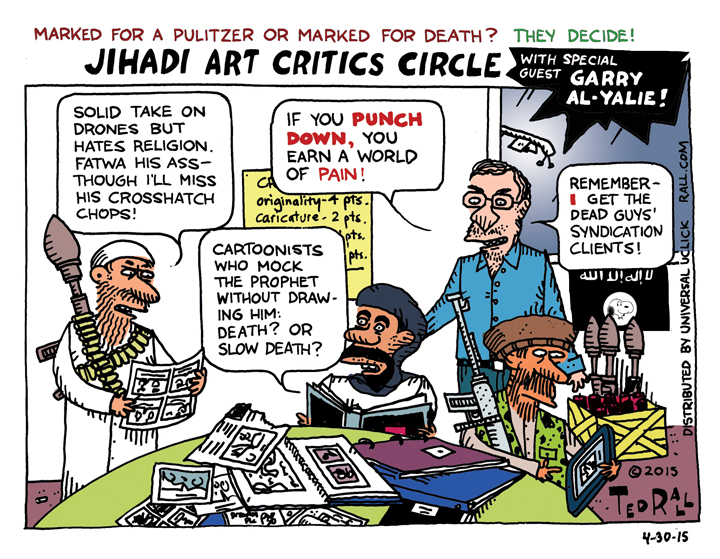

Supporters of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) are plotting to assassinate Australian and American cartoonists, Foreign Policy magazine is reporting.

As an American cartoonist who prefers not to get assassinated, I believe this is an extremely worrisome story.

As you can probably imagine, I have been giving a lot of thought to the possibility that Australian and American cartoonists might get blown away à la Charlie Hebdo, and even more consideration to the possibility that I might be one of them.

As a result of said thinking, I have this to say: If some ISIS asshole kills me, it’s totally Obama’s fault.

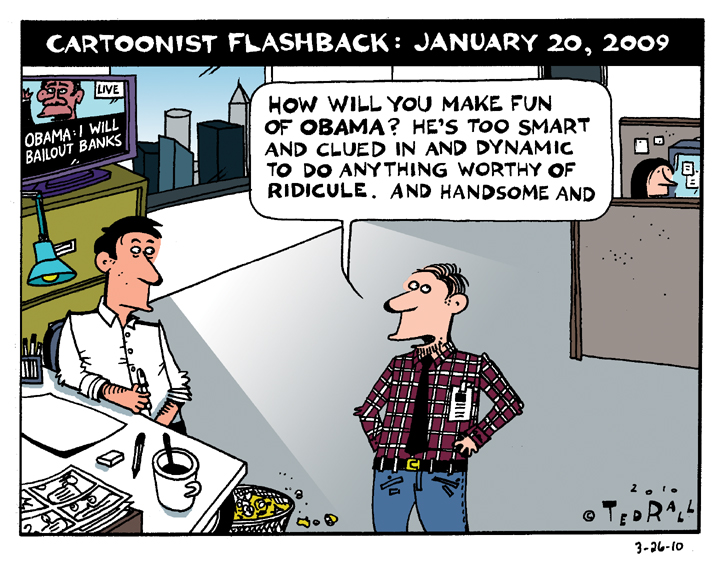

Since at least a year ago, the Obama Administration has pulled out all the stops to stop wannabe jihadi American citizens and residents from traveling to Syria, typically via Turkey, to join the Islamic State.

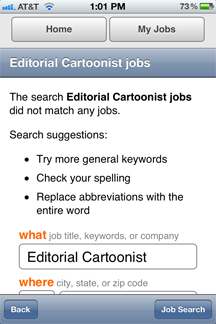

In October, the FBI arrested Mohammed Hamzah Khan, 19, at Chicago’s O’Hare airport. He faces 15 years in prison for trying to go to Syria to join ISIS. They grabbed Adam Dandach, 20, at Orange County California’s John Wayne airport, of all places, for the same thing. This past February, it was three guys from Brooklyn of Central Asian ethnic descent, this time at JFK. In April, four Somali-Americans in Minneapolis. Scores of Americans have been arrested by federal authorities while trying to join ISIS.

To which I, possible future dead cartoonist, ask: WTF?

Why not let them leave?

As I wrote recently, the legal basis for these arrests is skimpy. But never mind the morals or the law. What about common sense?

I thought the idea was to fight them over there so we wouldn’t have to fight them here, right? So, about these self-radicalized guys — why not let them go to Syria?

The word is already getting out among ISIS fans that it’s getting hard to travel from the U.S. to Syria, and that you might get slammed with a “material support to a terrorist organization” charge if the feds learn about your plans. Those who are stuck here in the States will naturally turn to Plan B: carrying out attacks here in the — yuck on this word — “homeland.”

Before he was accidentally blown up by an American drone this past January, Al Qaeda spokesperson Adam Yahiye Gadahn, a.k.a. Azzam the American, advised English-speaking would-be terrorists to think globally, kill locally:

“America is absolutely awash with easily obtainable firearms. You can go down to a gun show at the local convention center and come away with a fully automatic assault rifle without a background check and most likely without having to show an identification card. So what are you waiting for?”

I’ve followed politics and U.S. foreign policy my whole life, yet I can’t imagine the rationale for this policy of apprehending Americans for wanting to join ISIS. If they want to go, let them — hell, give them a first-class plane ticket.