Greetings from Mazar-i-Sharif

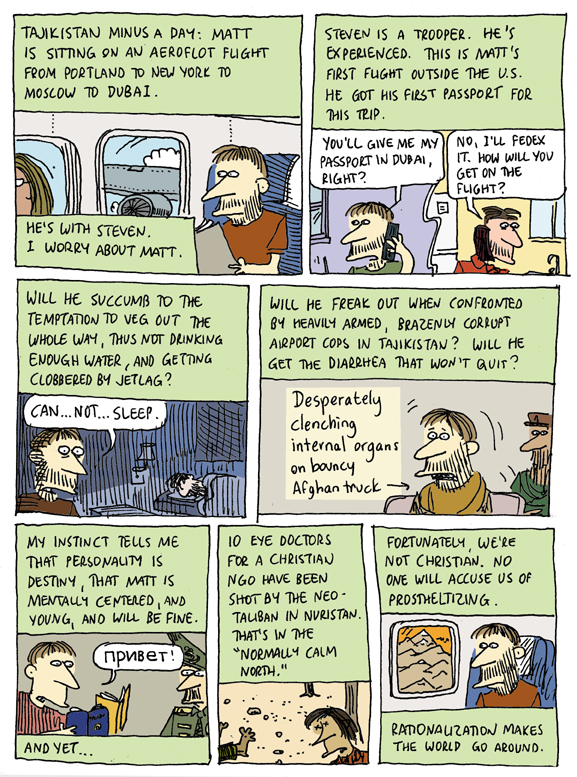

Matt Bors, Steven Cloud and I have just arrived in Mazar-i-Sharif, the fourth largest city in Afghanistan, the gateway to Uzbekistan, and about the hottest and dustiest place on earth. Don’t believe the Internet: It says it’s 81 here. More like 111.

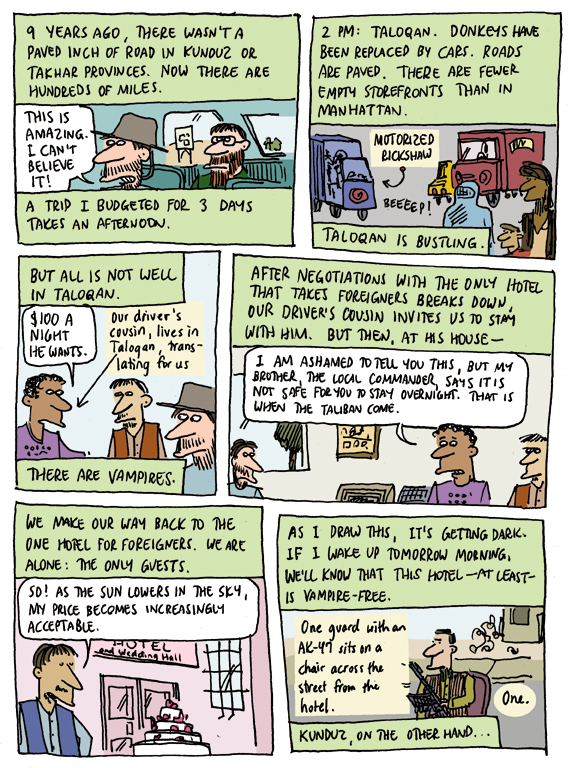

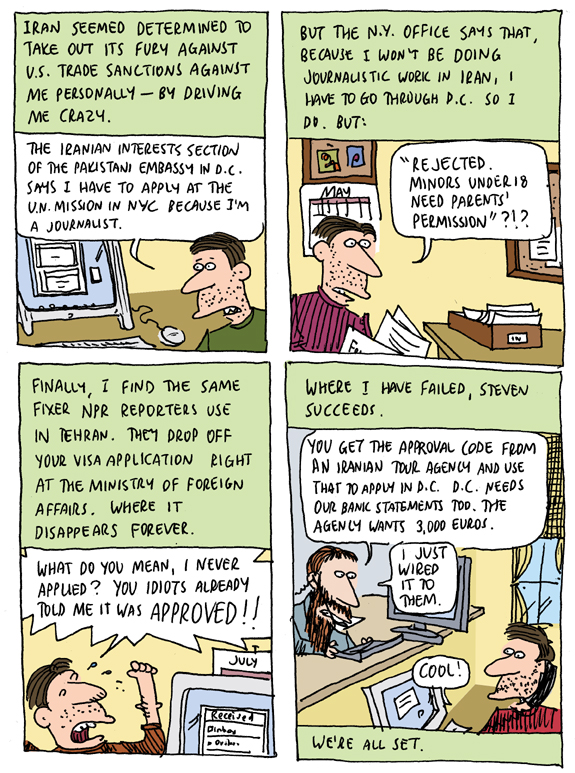

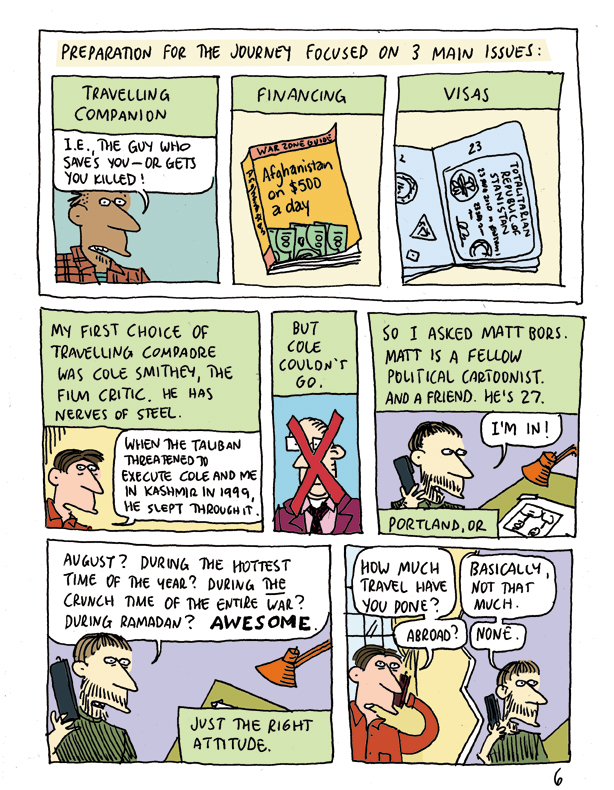

It was a brutal drive from Taloqan, where we spent two nights looking for my 2001 fixer Jovid. (Follow my daily cartoon blog to find out whether or not we were successful. It was much, much worse in 2001, before road-paving, though. Yes, most major roads in Kunduz and Takhar provinces are now paved. This might have made a favorable impression on Afghans prior to 2003, but now it appears to be too late. Everyone knows the Taliban will soon be back in charge.

Women are still in burqas, same as it ever was. Business is booming, but poverty remains widespread. And American troops are still acting like assholes: buzzing through town at high speeds, terrorizing the Afghans they’re supposedly there to help.

We plan to enjoy a few days of R&R before heading west toward Maimana. Mazar has some major architectural treasures we plan to start seeing tomorrow morning.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: The Libertarian War on Free Speech

It’s the Economics, [REDACTED]

SOMEWHERE IN AFGHANISTAN—Two months ago long-time White House correspondent Helen Thomas got fired by her employer, the Hearst newspaper conglomerate, in response to her off-the-cuff slam at Israel. I criticized the firing on free speech grounds.

“Free speech must be defended no matter what—even that of cranky anti-Semitic columnists (if that’s what Thomas is/was),” I wrote. “Unless we are truly free to say what we think—without fear of reprisal—free speech is not a right. It is merely a permission.”

I received many letters in response. Most people disagreed with me.

A letter from Joseph Just was typical, but better written than most (which is why I quote it here):

“Ms. Thomas has been denied not one of her constitutional rights. She faces no fine, legal censure or criminal charges for saying what she said. Her immunity from the threat of such sanction (rather than immunity from being, shall we say, ‘asked to resign’) is what the First Amendment protects. The only reprisal Ms. Thomas has materially suffered (in addition to the public opprobrium directed at her) is the loss of her job at Hearst. She held her job at the pleasure of her employers, and if they decide that due her comments they no longer want her around, they are not obligated to retain her. She is not—indeed, none of us is—entitled to a forum…particularly a paid one.”

Legally, Just is right. The First Amendment does not protect us from economic reprisals. I was arguing that employers ought to choose not to fire people for speaking their minds.

Unfortunately, employers seem to be whacking people for what they say outside of work more than ever. Countless workers have gotten canned for statements they made on non-work-related blogs and social networking sites. Even more worrisome, many citizens don’t have a problem with that. Even self-described leftists have embraced the libertarian extremist view that you have the right to say whatever you want—but don’t expect to be able to feed yourself or your family if you do.

Posters at Democratic Underground, a left-of-center discussion site frequented by that rarest and most appreciated of creature, balls-out Democrats, has long been a community I’ve been able to count upon. On the Thomas issue, however, they sound like Sean Hannity. “Private organizations aren’t and shouldn’t be required to put up with speech they don’t agree with,” said one poster.” “Free speech is not guaranteed to be speech without consequences,” wrote another.

“Freedom of speech doesn’t mean freedom from criticism,” argued a third. “It means that you can say what you want without the threat of being thrown in jail.”

Funny, these same libertarians would have freaked out if the artists who created the Danish Mohammed cartoons had all gotten fired by their newspaper.

True, the First Amendment doesn’t protect your right to keep your gig as a community banker even though you wear a swastika T-shirt and whistle the Horst Wessel song on your lunch break.

But it ought to.

If the First Amendment is to truly protect freedom of speech, it must allow Americans to say and think whatever the hell they want, no matter how outrageous. So the First Amendment should be expanded to prohibit economic reprisals.

As things stand, the First Amendment is pure sophistry, a bad joke. A right to free speech, ostensibly protected in order to encourage the vigorous exchange and discussion of ideas that make a society truly free, is meaningless if a person risks getting fired each time he opens his mouth. While it is true that some people will decide that the risk of professional opprobrium and unemployment is worth it, most people won’t. And don’t.

Consider the other basic right guaranteed under the First Amendment: freedom of worship. Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act makes it illegal for an employer to fire you because of your religion (or lack thereof). (There’s an exception for employers that are religious groups.) The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has filed numerous federal lawsuits against companies it accused of reprisals against employers due to their religious preference.

Why is religious expression granted greater protection than, say, political speech? It’s not because religion is inherently less offensive. To many people, religion is itself offensive.

The distinction is arbitrary and, ironically, wholly political: in the secular American republic, you have the right to say that your God is better than anyone else’s God without fear of losing your job. If Helen Thomas had thrown down a Muslim prayer carpet on the White House lawn and prayed toward Mecca, it would have been offensive to many people—she’d still be working.

Another way to examine my proposed expansion of free speech protections is to look at it from the standpoint of an employer. What would a boss stand to lose if the First Amendment were strengthened?

Certainly, employers would lose a measure of control over their workers. They would risk embarrassment. But they would also gain a big measure of CYA: when one of their staff did or said something outrageous (but constitutionally protected), they could point to the First Amendment and shrug their shoulders. In the Helen Thomas example, Hearst execs could say: “What can we do? She has the right to say whatever the hell she wants.”

Which of course she should.

(Ted Rall is in Afghanistan to cover the war and research a book. He is the author of “The Anti-American Manifesto,” which will be published in September by Seven Stories Press. His website is tedrall.com.)

COPYRIGHT 2010 TED RALL