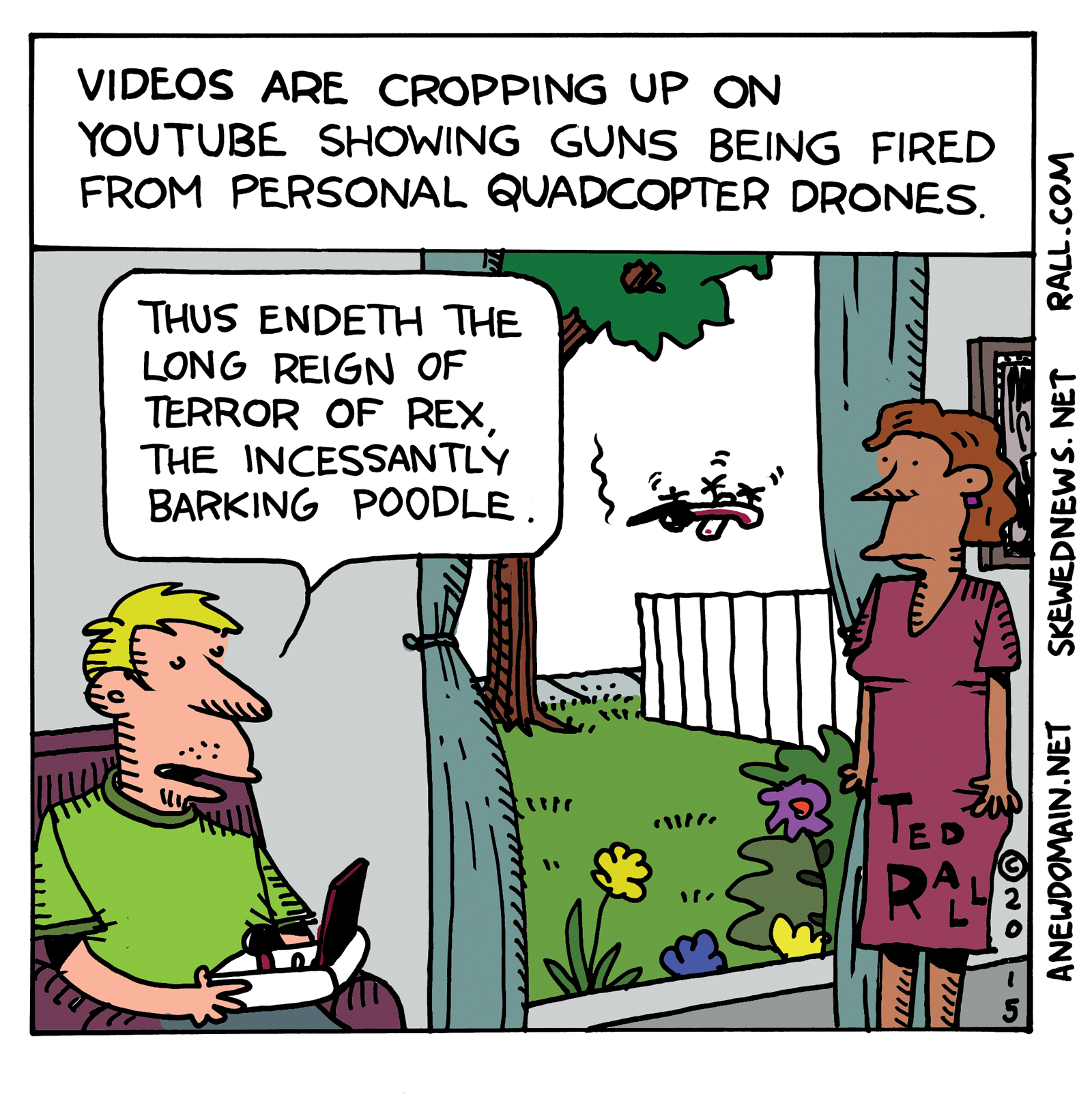

Originally published by ANewDomain:

Ted Rall-LAPD-LATimes Battle: New Tape Proves Cops Lied [exclusive]

EXCLUSIVE — Audio engineers hired by Ted Rall and aNewDomain today released a cleaner version of an audio tape Los Angeles police used to convince Los Angeles Times editors to fire political essayist and cartoonist Ted Rall early this week. It is damning.

On the tape, you can clearly hear a female bystander shouting at the LAPD officer who’d stopped Rall for jaywalking to “take off his handcuffs.” She yells this twice. Officer Will Durr responds first with a “No, no, no … ” and then by whistling loudly into the mic. Listen for yourself, below.

The LAPD and the Times have been claiming that the original version of the tape, released on Monday, proved the officer did not handcuff Rall or otherwise rough him up as Rall had written in a May 2015 Times column. They claimed the tape proved Rall was lying. That was the basis for the Times abruptly dumping him this week. But this newly enhanced tape clearly proves that the cops are lying — and it even suggests cops might have knowingly tampered with the tape. Why? We’re pursuing this developing story. For now, here’s what Ted Rall has to say about the tape and what you’ll hear on it. – Ed

aNewDomain — We now have an enhanced version of the LAPD tape that cops used to convince the Los Angeles Times to fire me as its political cartoonist and blogger this week.

On the cleaned-up version of the tape, which you can hear below, just advance the recording to minute 3:30. You’ll hear a female witness, one the LAPD told my former editors at the Times I was lying about, and one they said didn’t exist, on the tape. She protests: “He was just jaywalking … you need to take off … you need to take off his handcuffs.”

She says that at 3:30 and repeats it at 3:50.

To this, LAPD Officer Will Durr replies: “No, no, no, no, no.”

When she persists in protesting the cop’s handcuffing me, LAPD officer Durr whistles. At the time of the incident, I was puzzled by his whistling, which is unusual behavior for a cop. Now I believe it’s his technique to tamp down sounds (like her) that he doesn’t want on the recording. (The recorder was on his uniform, secretly.) Any way you look at it, though, this proves he and the LAPD are lying: Cops lied when they said that I didn’t get handcuffed, lied when they said I lied about the presence of protesting witnesses, and lied when they went to my Times editors and called me a liar.

Listen for yourself:

So we know the officer deliberately used whistling to alter the recording. It is also clear that he deliberately muffled it.

It’s the media’s job to question authority, not to blindly defend it and execute on its behalf.

Even in its defense of the LAPD, the LAT couldn’t be bothered to do due diligence. Editors made no effort to investigate long-time traffic cop Will Durr’s bizarre claims that he has never ever handcuffed anyone. We disproved that cop’s lie yesterday. They didn’t even bother searching their own website.

If they can’t type “Will Durr” into a search field, how can they be bothered to track down a sound engineer in L friggin A?

Classic Streisand Effect: In their attempt to discredit me and destroy my reputation as a journalist, they wound up discrediting themselves and further eroding their own reputation, which has already been destroyed by decades of police brutality, systematic corruption and fatal police shootings of one unarmed black man after another.

Two shorter clips, enhanced differently, follow. Listen to them, below.

So the cops lied. And there are other questions …

The main question is: Why? Why would they lie?

The audio tape was not a public record. No one requested my permission, required under California law, to release it. Did The Los Angeles Times file the required papers to get it?

Did The Los Angeles Times approach the LAPD to request the tape, or did the cops (or a third party, like the LAPPL police union, or the pension fund for cops) approach them?

Did the LAPPL (the police union) which has been gloating on its blog that the Ted Rall incident should be a “lesson” other media outlets should learn from — go out of their way to get me out?

Why would the LAPD spend taxpayer money to dig out an ancient audio tape and go to the trouble of doctoring it, if they did, and transcribing it, which they did, and walking it over to the Times to get me fired?

Under LA law and LAPD rules, an officer must include contemporaneous date, location and other identifying data within each uninterrupted recorded incident — otherwise it’s a violation of citizens’ privacy rights. That info isn’t on the tape, which means it was either illegal, or it was spliced out/tampered with. Which was it?

Also, was it illegal for the Times or the LAPD to get the tape, which isn’t public information, without my approval? Our legal analyst Tom Ewing will be following up with analysis around that question later in the day.

Does the fact that a big chunk of The Los Angeles Times is now owned by Oaktree Capital, an investment firm that itself is powered by billions in investment from the Los Angeles Fire and Police Pension Fund, have anything to do with this?

This pension fund, points out investigative reporter Gina Smith, has previously demanded firings of editorial writers and commentators at a San Diego daily, one that the LA Times’ parent company, Tribune Publishing, just bought. Watch for that report, too.

Notes on Audio Enhancement Methodology

The long enhanced version posted here was processed by a technician who wishes to remain anonymous because he lives in Los Angeles, is African-American, and has frequently been harassed by the LAPD. Here is his statement about how he was able to isolate the sound of the eyewitness to me being handcuffed — the one who the Times said didn’t exist, about an act the LAPD said never happened: “I used a noise reduction plugin to diminish hiss, handling, and street noise. An equalizer cuts low frequency rumble and boosts the upper mid range to enhance intelligibility. A limiter brings up the overall volume.”

A different person, who lives near Los Angeles and also prefers to remain anonymous because she fears retaliation by the LAPD, used this longer version to create the two shorter clips. She said: “I’m using audio repair software to remove surface/street noise with de-noise filters, and an equalizer targeting the vocal ranges of the bystanders.”

I have hired a professional audio technician based in Los Angeles to further clean up the tape provided by the LAPD. I will post the results when I get them.

Additional reporting: Gina Smith, Nancy Imperiale and Tom Ewing of aNewDomain and SkewedNews.

Hillary’s other big albatross is the widespread perception among the Democratic Party’s progressive base that she is not one of them.

Hillary’s other big albatross is the widespread perception among the Democratic Party’s progressive base that she is not one of them.  I say the media, rather than Republican primary voters, because his poll numbers have risen since he said that many Mexicans crossing the border illegally are criminals and rapists.

I say the media, rather than Republican primary voters, because his poll numbers have risen since he said that many Mexicans crossing the border illegally are criminals and rapists.  The Too-Much-Information Bernie Sanders Attack

The Too-Much-Information Bernie Sanders Attack

Rather she comes to us via the very old tradition of wives inheriting their politician husband’s status, like the widow of Hubert Humphrey, who inherited his senate seat, or Benazir Bhutto of the universally acknowledged patriarchy, Pakistan.

Rather she comes to us via the very old tradition of wives inheriting their politician husband’s status, like the widow of Hubert Humphrey, who inherited his senate seat, or Benazir Bhutto of the universally acknowledged patriarchy, Pakistan. And never mind the ongoing salary differentials between male and female workers, or hey, ever noticed how male the room looks (see crowd image, at right) when the camera pans across members of Congress during a State of the Union Address?

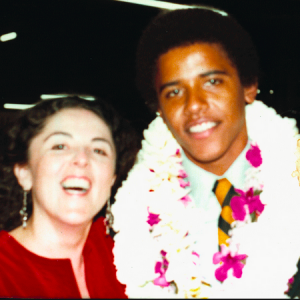

And never mind the ongoing salary differentials between male and female workers, or hey, ever noticed how male the room looks (see crowd image, at right) when the camera pans across members of Congress during a State of the Union Address? This is despite nearly seven years in office, during which, by all accounts (said accounts sourced from black civil rights leaders), the president has studiously avoided pressing for policy measures that would benefit black people — aside from a few measured statements following racially-charged controversies. Recall, after the Florida shooting of Trayvon Martin (pictured at left), Obama’s comment was: “If I’d had a son he would have looked like him.”

This is despite nearly seven years in office, during which, by all accounts (said accounts sourced from black civil rights leaders), the president has studiously avoided pressing for policy measures that would benefit black people — aside from a few measured statements following racially-charged controversies. Recall, after the Florida shooting of Trayvon Martin (pictured at left), Obama’s comment was: “If I’d had a son he would have looked like him.”  Tokenism is what the system sells you and me. And to the ruling classes, ideas and ideology are everything.

Tokenism is what the system sells you and me. And to the ruling classes, ideas and ideology are everything.  The regime of Bush and Cheney wound up hated and reviled, but does anyone doubt that their long run on the high end of the opinion polls was extended by the Administration’s Uncle Toms, General Colin Powell (pictured left) and Secretary of State Condi Rice (pictured below right)?

The regime of Bush and Cheney wound up hated and reviled, but does anyone doubt that their long run on the high end of the opinion polls was extended by the Administration’s Uncle Toms, General Colin Powell (pictured left) and Secretary of State Condi Rice (pictured below right)? the U.S. — polls consistently show that about half of American voters would like to get rid of capitalism and replace it with socialism and communism. This is remarkable considering that these ideologies are rarely discussed here, except as objects of scorn and terror.

the U.S. — polls consistently show that about half of American voters would like to get rid of capitalism and replace it with socialism and communism. This is remarkable considering that these ideologies are rarely discussed here, except as objects of scorn and terror. Because Hillary Clinton might become president. Because Sheryl Sandberg (left) made friends with Mark Zuckerberg and so scored a great job at Facebook, which gave her an in to pitch and promote her book.

Because Hillary Clinton might become president. Because Sheryl Sandberg (left) made friends with Mark Zuckerberg and so scored a great job at Facebook, which gave her an in to pitch and promote her book.