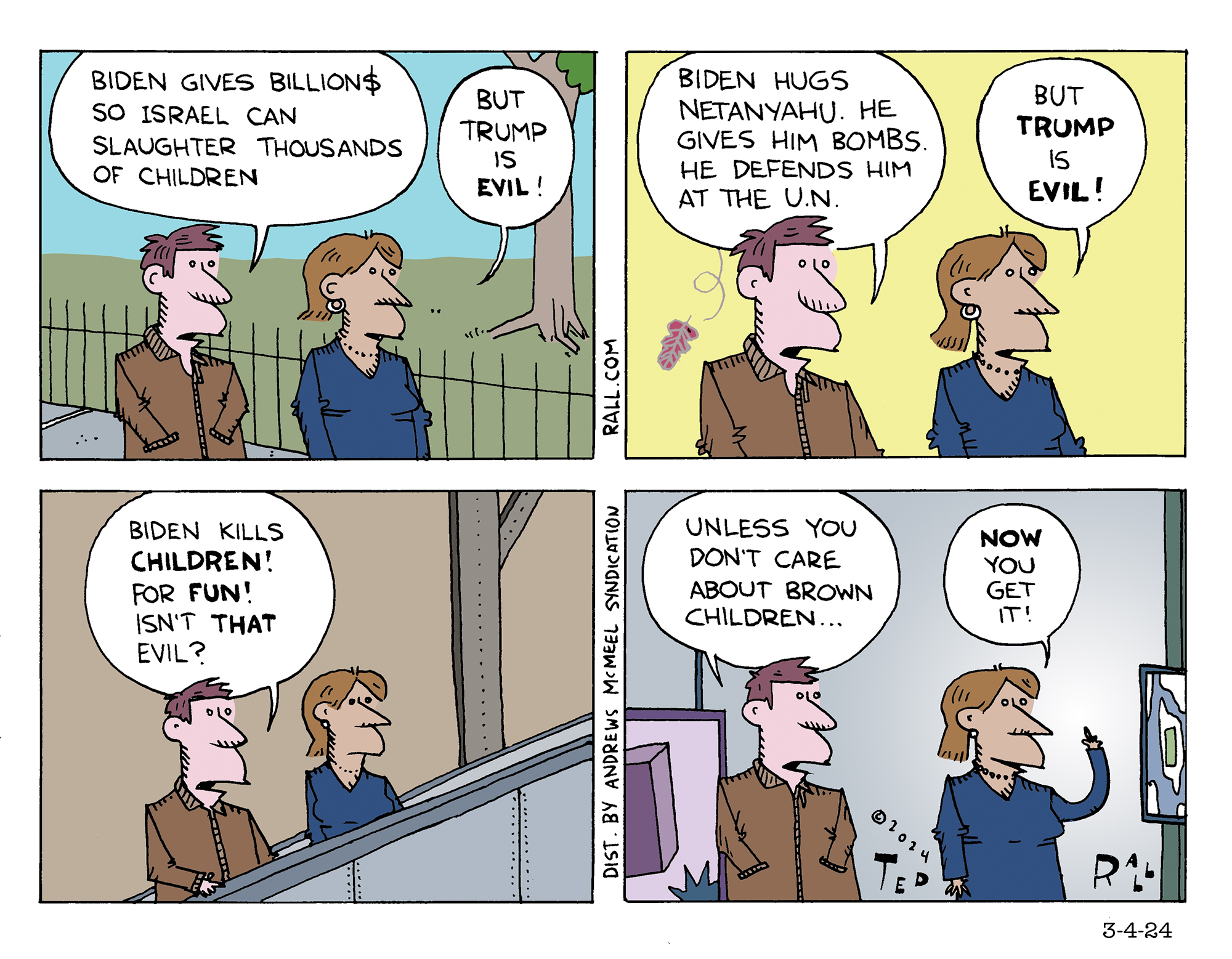

Many people who typically vote Republican but dislike Trump, and others who typically vote Democratic but dislike Harris, are wrestling with a fundamental dilemma of the voter who lives in a duopoly.

Many people who typically vote Republican but dislike Trump, and others who typically vote Democratic but dislike Harris, are wrestling with a fundamental dilemma of the voter who lives in a duopoly.

A vote is an endorsement. A vote declares to the world: “I approve of this candidate.” There is no half-vote. A vote is binary: yes or no. If your vote helps someone win who goes on to do something awful, their sins are partly your fault.

If there are only two major-party candidates, and both seem likely to commit an atrocity if they win, the moral and rational alternative is clear: vote for a third-party or independent candidate whose odds of carrying out a heinous act appear to be low, or boycott the election.

For the 61% of Americans who oppose sending more weapons to Israel, this condition has been met. Kamala Harris and Donald Trump are both enthusiastic supporters of Israel’s genocidal war against Palestinian civilians in Gaza, Lebanon and the West Bank. Both have promised to send more bombs, more missiles, more money and more intelligence to the Israelis. A vote for Harris is a vote for more genocide. So is a vote for Trump. If you vote for either the Democrat or the Republican, the blood of every Palestinian who dies or gets maimed after January 20th will be on you.

I am not saying this to make you feel guilty. I am merely stating a fact.

If they care to vote at all, pro-Palestinian voters can support Jill Stein, Cornel West, Chase Oliver or someone else. But then they must contend with the strategic voting fallacy.

Strategic voting, or “lesser of two evils” voting, is the act of casting a ballot in favor of a candidate you do not support, in order to prevent a second candidate you oppose more, from winning. By definition, because non-duopoly candidates are unlikely to win, a vote for someone other than a Democrat or a Republican is a “wasted” vote that, de facto, supports the major-party candidate you hate most. Aside from the self-alienating cognitive dissonance of consciously endorsing a politician whose policies of which you do not approve, strategic voting is deeply illogical and mathematically ridiculous.

First and foremost, it is statistically impossible—beyond the point of winning-the-Lotto odds—that your single vote could ever change the outcome of an American election at the state or national level. This is not to say that an election can’t be close. The 2000 Bush v. Gore presidential race came down to 537 votes that determined the pivotal state of Florida; the 1916 contest between Woodrow Wilson and Charles Hughes boiled down to 3,420 votes in California. But the odds that one vote can change the result of an American presidential election are so vanishingly small as not to be worthy of serious consideration by anyone with more than two IQ points to rub together.

A statistical analysis of the 2008 election published in the academic journal Economic Inquiry by Andrew Gelman, Nate Silver and Aaron Edlin proves this point. “One of the motivations for voting is that one vote can make a difference. In a presidential election, the probability that your vote is decisive is equal to the probability that your state is necessary for an electoral college win, times the probability the vote in your state is tied in that event,” the authors noted. “On average, a voter in America had a 1 in 60 million chance of being decisive in the presidential election.”

If you vote to “make a difference,” you’d get better results from playing a classic Pick-6 Lotto game; odds of winning the jackpot are 1 in 32 million. Unlike voting, it pays.

True, your vote might determine who sits in the Oval Office the next four years. It’s never happened before. It’s never even been close. Statistically, 537 votes in Florida was not close. Would you go to a job interview where your odds of getting hired were 1-in-537? It would be irrational, just as it would be crazy to avoid flying—even though the odds of dying in a plane crash (1 in 11 million) are much higher than your vote tipping a national election.

Strategic voting requires precise analysis of perfectly accurate polls capped by a completely subjective determination of whether a candidate has a viable chance of winning.

Setting aside the challenges faced by pollsters trying to sample a population’s opinions from mobile phones rather than landlines, a problem illustrated by the many polling organizations who failed to predict Trump’s 2016 victory, high-quality polls are subject to a margin of error of several percentage points. In a tight race, in which the margin of a win can be within that margin, a poll is as useful as a coin flip. Finally, strategic voters must ask themselves: assuming I can find a poll that I totally believe, where is the numerical tipping point where a race becomes so skewed in my state that I should free to vote my conscience, i.e. for a third-party or independent candidate, or not at all?

In Montana, where Trump leads Harris 56-39, it’s safe to say the former president has the state in the bag. Montana voters tempted to cast a protest vote against the Israelis’ genocide in Gaza needn’t lose much sleep by filling in the oval for Jill Stein. It’s a different affair in the battleground state of Pennsylvania, where Harris leads Trump by one point, 49-48, well within the margin of error—that is, of course, assuming these polls are right and that, if they are, they won’t change much between now and when you cast your vote.

What about a state where one candidate leads 55-45? A ten-point difference would be hard to overcome, and it wouldn’t be considered a swing state, but it’s not impossible—such things have happened before.

This is where the absurdity of strategic voting escalates even further.

What constitutes a close race? A close-enough race to believe (falsely, as Nate Silver and his friends proved in their study that your single vote could affect the outcome)? 51-49? Of course. (Though it’s not true.) 75-25. Of course not. (But that’s no less true than the 51-49 scenario.) 53-47? Maybe?

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. His latest book, brand-new right now, is the graphic novel 2024: Revisited.)

3 Comments.

One correction. The 2000 election was decided by a single vote. 5-4, the Supreme Court justices decided Dick Cheney should be running the country, and they voted in his dupe, George W. Bush.

I disagree that strategic voting is “the lesser of two evils.” With Harris or Trump heading toward the White House about 100 days, it’s more “the least of three evils.” I don’t write that to be facetious or gratuitous. Trump is an oaf: Bill Clinton without the ability to mask his satyr-like tendencies. Harris is a “company man.” She will do exactly what she is told by her controllers.

Granted, a vote for West or Stein doesn’t mean either is incapable of atrocities or stupidities. And I would submit that permitting an evil to continue — like leaving Gitmo open while there are people sitting in it — is just as bad as actively initiating evil. But a vote for West or Stein does permit a concretization of protest. People can see they aren’t “throwing away their vote” alone.

When a third-party candidate gets 1% or 2% of the vote (or a couple of third-party candidates draw 5% of the vote), that’s a sign the smart politician needs to absorb: In a close contest, that’s the difference between having balloons rain down on you and having to admit that you didn’t even write a concession speech and closing up your pay-to-play charity.

“Strategic voting” is less “a fundamental dilemma of the voter who lives in a duopoly” than yet another, of many, imposed cynical ploys to keep US citizens constrained to, if not content with, their system that amounts to pathetic huffing and puffing about “democracy,” which, if it ever existed, has devolved into “plutocracy – with American (well-learned, self-delusional) characteristics.”

The term “strategic” must be a contribution of Frank Luntz to evoke the (intentionally) false specter of the possibility of sly and cunning, effective (give me a break!) individual action.

Taking the Tweedle Dum/Tweedle Dee system seriously is an indicator of a sort of totalitarianism of futile freedom.

Note that 40% of eligible voters routinely do NOT partake in the quadrennial clash of false savior cults with an even greater rejection of the “mid-term” choice of Zionism representatives in congress.

As a college prof who teaches statistics, I really enjoyed this article and will use it in class. However, I have to take note with one statement. “In a tight race, in which the margin of a win can be within that margin, a poll is as useful as a coin flip.”

That is not really true. If the error margin (confidence interval) is set at the 95%tile, which is typical, the more points you are in the lead, the greater the chance of victory. For example, if Trump is up 52%-48% against Harris in a poll and there is an error margin of 6 points, Trump still has a better chance of winning than Harris. The chance that he really has a majority is merely less than 95%, but it is greater than 50%.

The term “statistical tie” is frequently used but is a misnomer.

Other than that small point, I really dig the article.