Though their number is steadily dropping, especially among Republicans, most Americans support Ukraine in its conflict with Russia. I have a question for you pro-Ukraine peeps: imagine you were Russian President Vladimir Putin just shy of a year ago.

What would you have done in his place?

Putin faced an impossible situation. He knew that an invasion would bring Western sanctions and international opprobrium. Staying out of Ukraine, however, would weaken Russia’s geopolitical position and his political standing. Caught in an updated version of Zbigniew Brzezinski’s 1979 “Afghan Trap,” he acted like any Russian leader. He chose strength.

The story (now disputed) is that National Security Advisor Brzezinski convinced President Jimmy Carter to covertly support the overthrow of the Soviet-aligned socialist government of Afghanistan and arm the radical-Islamist mujaheddin guerrilla fighters. Determined not to abandon an ally or allow destabilization along its southern border, the USSR was drawn into Brzezinski’s fiendish “Afghan Trap”—an economically ruinous and politically demoralizing military quagmire in Afghanistan analogous to America’s ill-fated intervention in Vietnam.

A year ago, Ukraine was a trap for Russia. Now, as Ukraine’s requests for increasingly sophisticated weaponry pile up on Biden’s desk, it’s one for the U.S. as well.

All nations consider friendly relations with neighboring countries to be an integral component of their national security. Big countries like the United States, China and Russia have the muscle to bend nearby states to their will, creating a sphere of influence. The Monroe Doctrine claimed all of the Americas as the U.S.’ sphere of influence. Russia sees the former republics of the Soviet Union the same way, as independent, Russian-influenced buffer states.

None of the 14 countries along its 12,514 miles of land borders is as sensitive for Russia as Ukraine. When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941 they passed through Ukraine across its 1,426-mile border with Russia. Four years later, 27 million Soviet citizens, 14% of the population, were dead.

Adding insult to injury from a Russian perspective was the fact that many Ukrainians greeted the Nazis as liberators, collaborated with the Nazis and enthusiastically participated in the slaughter of Jews.

America’s most sensitive frontier is its southern border with Mexico, which the U.S. has invaded 10 times. We freaked out over China’s recent incursion into our air space by a mere surveillance balloon. Imagine how terrified we would be of Mexico if the Mexican army had invaded us, butchered one out of seven Americans and destroyed most of our major cities. We would do just about anything to ensure that Mexico remained a friendly vassal state.

Post-Soviet Ukraine had good relations with Russia until 2014, when President Viktor Yanukovych was overthrown in the Maidan uprising—either a revolution or a coup, depending on your perspective—and replaced by Petro Poroshenko and subsequently Volodymyr Zelensky.

Ethnic Russians, a sizable minority in Ukraine, read the post-Maidan tea leaves. They didn’t like what they saw. The Maidan coalition included a significant number of neo-Nazis and other far-right factions. It was backed by the U.S. to the extent that Obama Administration officials handpicked Ukraine’s new department ministers. Poroshenko and Zelensky were Ukrainian nationalists who attempted to downgrade the status of the Russian language. Statues of and streets named after Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera went up across the country.

Low-grade civil war ensued. Russian speakers in the eastern Dombas region seceded into autonomous “people’s republics.” When Russia annexed Crimea, the local Russian majority celebrated. Ukraine’s post-coup central government attempted to recapture the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics for eight years, killing thousands of Russian-speaking civilians with shelling.

Try to imagine an analogous series of events in North America. Mexico’s democratically-elected pro-American president gets toppled by a violent uprising supported by communists and financed by Russia. Mexico’s new president severs ties with the U.S. Their new government discriminates against English-speaking American ex-pats and retirees in beach communities near Cancun, who declare independence from the Mexican central government, which goes to war against them.

Next, Mexico threatens to join an anti-U.S. military alliance headed by Russia, a collective-security organization similar to the former Warsaw Pact. The Pact’s members pledge to treat an attack on one as an attack on all. If Mexico joins the Pact and there is a border dispute between the U.S. and Mexico, Russia and its allies could respond with force up to and including nuclear weapons.

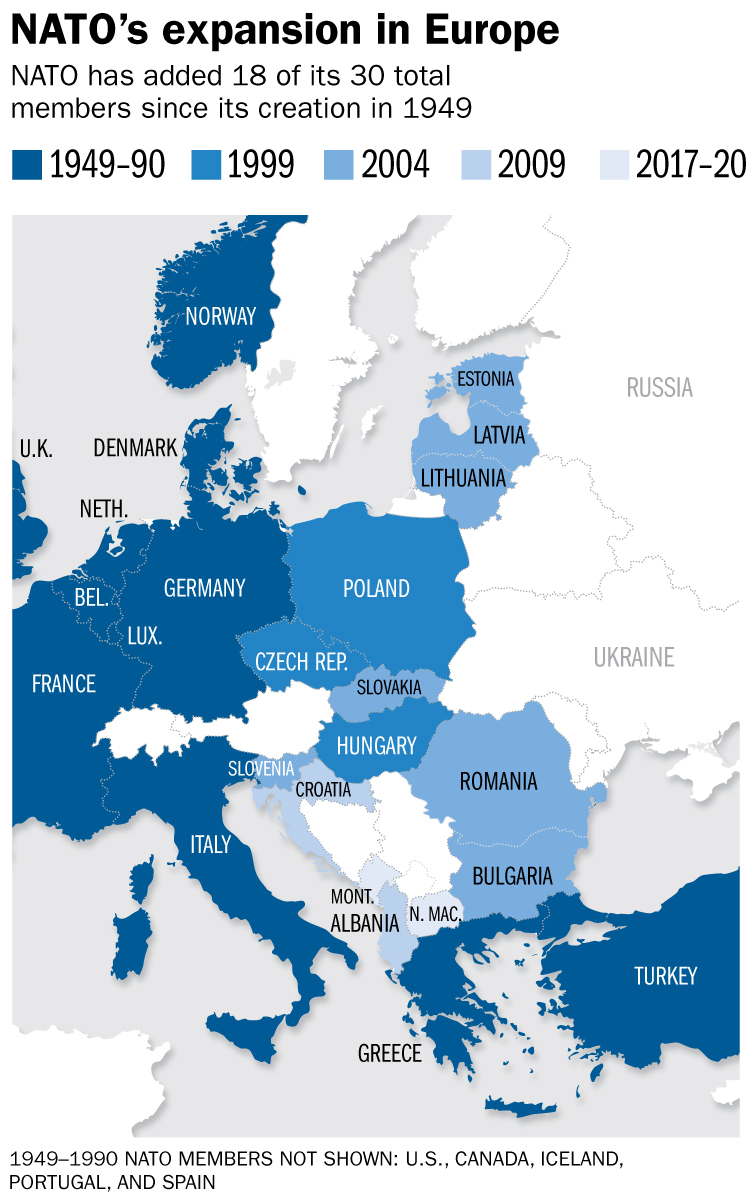

Zelensky has repeatedly expressed his desire to join NATO—an anti-Russian security alliance—since assuming power in 2019. Ukraine probably wouldn’t qualify for NATO membership anyway. But it’s easy to see how the Ukrainian leader’s statements would cause offense, and fear, in Moscow.

Like Ukraine, Mexico is a sovereign state. But independence is relative. Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun, as Mao observed. So when you are a smaller, weaker country bordering a bigger, stronger country—Mongolia next to China, Ukraine next to Russia, Mexico next to the United States—prudent decision-making takes into account the fact that you have fewer gun barrels than your neighbor. Offending the biggest dog in your neighborhood would be foolish. Spooking it would be suicidal.

Supporters of Ukraine call the Russian invasion “unprovoked.” Justified or unjustified? That’s subjective. But it was provoked. I have asked pro-Ukraine pundits what Biden or any other American president would have done had they faced the same situation as Putin. They refuse to answer because they know the truth: the United States would behave exactly the same way.

Look at Cuba: the Bay of Pigs, silly assassination attempts against Fidel Castro, six decades of severe economic sanctions. Then there’s Grenada. Reagan invaded a tiny island 2,700 miles away from the southern tip of Florida in order to overthrow a socialist prime minister and save American medical students who neither needed nor wanted saving. If Mexico, which shares a long border with the U.S., were to turn anti-American, how long do you think it would be before the U.S. Army invaded an 11th time?

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

1 Comment.

Was the U.S. wrong to invade Mexico, or is Russia right to invade Ukraine?

Or is it just that the U.S. is always wrong and Russia is always right?