When you tell people you’re a cartoonist, one of the first things they ask you is whether you’ve ever had a cartoon published in The New Yorker. I don’t blame them. Everyone “knows” that running in the same pages that showcase(d) Addams and Chast proves you’re one of the best.

The marketing hype behind New Yorker cartoonist and cartoon editor Bob Mankoff’s new memoir — featuring something I really am jealous about, a “60 Minutes” interview — further cements the magazine’s reputation as cartooning’s Olympus.

“For nearly 90 years, the place to go for sophisticated, often cutting-edge humor has been The New Yorker magazine,” says Morley Safer.

As is often the case, what everyone knows is not true.

Here’s a challenge I frequently give to New Yorker cartoon proponents. Choose any issue. Read through the cartoons. How many are really good? You’ll be surprised at how few you find. But don’t feel bad. Like the idea that the U.S. is a force for good in the world, and the assumption that SNL was ever funny, the “New Yorker cartoons are sophisticated and smart” meme has been around so long that no one questions it.

From the psychiatrist’s couch to the sexless couple’s living room to the junior executive’s summons of his secretary via intercom, New Yorker cartoons are consistently bland, militantly middlebrow, and mind-numbingly repetitive decade after decade.

Which is fine.

What is not fine is not seeing fluff for the crap that it is.

The New Yorker is terrible for cartooning because it prints a lot of awful cartoons, and uses its reputation in order to elevate terrible work as the profession’s platinum standard.

They pay pretty well. Which prompts too many talented artists, who under a better economic and media model would produce interesting, intelligent, great cartoons (and did so, in the alternative weekly newspapers of the 1990s, for example), to pull their satiric punches and stifle their creativity. Of course, not every cartoonist follows the siren call to Mankoff’s office in the Condé Nast building. It is possible to make a living selling cartoons to other venues. I do. Still, the New Yorker casts a long shadow, silently asking a question one fears is heard by art directors everywhere: If you’re so smart and so funny and so talented, why aren’t you in The New Yorker?

Mankoff and his predecessors have created a bizarro meritocracy in reverse: bad is not merely good-enough, but the crème-de-la-crème. It’s like singling out the slowest runners in a race and awarding them prizes and endorsements. Some runners, devoted to excellence and the love of competition, will keep running as fast as they can. But fans will wonder why they don’t wise up.

What makes a cartoon good/funny? Originality, relevance, insight, audacity and random weirdness. (There are other factors, which I’ll remember after a minute after it’s too late.)

Originality in both substance and form, and in both writing and drawing, is the most important component of a great cartoon. It is rare to find. Cartooning is a highly incestuous art form; most practitioners slavishly copy or synthesize the work of their forebears. Editors and award committees (composed of editors) have short memories and no historical knowledge, which feeds lazy cartoonists’ temptation to present initially brilliant, but now hackneyed and recycled, ideas as their own. Other cartoonists’ punch lines, structural constructions, even their drawing styles, are routinely stolen wholesale; alas, media gatekeepers never have a clue. All too often, the plagiarists collect plaudits while the victims of their grand larceny of intellectual property die sad and alone.

Well, maybe not sad or alone. But annoyed over beer.

Give The New Yorker its due: since it reacts to trends and news in politics and culture, the magazine’s funniest cartoons can be relevant. Sadly, their single-panel gags say less than Jerry Seinfeld’s jokes about nothing. At best, name-checking Lady Gaga or hat-tipping Instagram elicits a knowing ha ha, they read the same stuff I do (i.e. The New York Times).

Mankoff’s book takes its title from the line of perhaps his greatest hit: “How about never — is never good for you?” This is an “nth degree” concept. What happens if the back-and-forth busy people often experience when they’re trying to set a rendezvous achieves its ultimate, most extreme conclusion? It also showcases anxiety and insecurity among the aspirational bourgeoisie, the not-so-secret sauce of New Yorker humor, for nearly a century. But what does Mankoff’s cartoon say? What does it mean?

A cartoon doesn’t have to be political to matter. “The Far Side” wasn’t political, but most of Larsen’s work reveals something about human nature to which we hadn’t previously given much thought. To be funny, a cartoon must rise above it’s-funny-cuz-it’s-true tautology. Mankoff’s “never” toon does not. Nor does the magazine’s famous “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” piece, drawn by Peter Steiner in 1993 (though Matt Petronzio’s post-Snowden update does).

If you can credibly reply “so what?” to a cartoon, odds are it’s not worth your time.

A great cartoon is funny because it’s dangerous.

A 19th century relic of the degrading “shape ups” depicted in the film “The Bicycle Thief,” The New Yorker‘s submission policy is a system — intentional or not, no one knows — that filters out originality and rewards a schlocky “throw a lot of shit at the wall and see if anything sticks” approach to cartooning. Every Wednesday morning, Mankoff holds court, looking over submissions of cartoonists who must present themselves in person rather than, say, email or fax their work. Because submissions must be fully drawn and the odds of acceptance increase with the number of cartoons presented, New Yorker artists deploy dashed-off, sketchy drawing styles that haven’t changed much since the 1930s.

Editors at other publications work with professional cartoonists they trust to consistently deliver high-quality cartoons, and help them hone one or two rough sketches to a bright sheen. The results are almost always better than anything that runs in The New Yorker — yet “60 Minutes” doesn’t notice.

“How much do the cartoonists make? Editor [David] Remnick will only say: nobody’s becoming a millionaire,” Safer says in the “60 Minutes” piece.

Well, Mankoff did. But that’s another story for another time.

(Support independent journalism and political commentary. Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2014 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

24 Comments.

60 Minutes used to be relevant … it was during the Reagan-era that corporate commercialism filtered its viability into a puppy show of much less time.

Tell me Ted, what neophyte (or perhaps even, “established”) cartoonists have tried copying your drawing-style? Were they also (or not) successful in mimicking your (explicit or implied) commentary?

DanD

DanD, I can think of three fairly prominent cartoonists off the top of my pointy little head who owe more than a little to my drawing style. And many more influenced by my structures and writing style. But it would be mean of me to out them here.

I’m just thinking that the education would be quite instructive, comparisons and all. I mean, is it like sports, where an aspiring young cartoonist may try for a time to be like you by way of repetition, ultimately do you so well that he does you better than you do?

I imagine such a freelance student would eventually find his own style, but what are your thoughts on such brands of plagieristic pedagogy?

DanD

Yes Dan, I think that’s exactly it. Certainly as a young cartoonist I started out copying other artists. As a child, I traced Charles Schulz. When I became interested in political cartooning, I mimicked Mike Peters.

As you get older, you’re supposed to find your own style. Unfortunately, that hasn’t always been the case.

In todays cartoon market not only is the ability to render/draw unnecessary it is a liability.

Count me among those who don’t get the appeal of those cartoons. This reminds me of the Seinfeld episode where Elaine tries to get several people to explain one of the cartoons to her, including a New Yorker editor, and no one can do it. I also remember reading a funny story about how a young Truman Capote — I think he was an intern — would deliberately lose the cartoons he didn’t like before they got to the editor’s desk; the quality of the cartoons getting published subsequently went up.

Ted, do cartoonists you know sincerely believe getting their cartoons into the New Yorker is something to aspire to, or is it just an easy way to get a paycheck? For example, PC Vey did funny stuff for Mad but his New Yorker stuff is dreck, so maybe it’s just easy money for a cartoon he can draw in 5 minutes.

It’s not easy money, SenatorBleary. You have to draw 20 or 30 or 40 cartoons to have a reasonable chance of publishing one. But yes, I do think most of these cartoonists do it more for the cash than the glory. There is glory, because most people don’t think about it enough to know that these cartoons suck. But there’s no real glory, i.e., the respect of your peers, or self-respect. That said, I think some cartoonists really do think it’s an accomplishment.

Look, I’d love to be in there. But I’m not willing to dumb down my work to get in.

Ted,

I see — yet another — iteration of the Same Old Problem. Who would put themselves through that? Answer?

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

A victim.

I recall a New Yorker cover by Charles Addams. Two luxury skyscrapers, facing each other. In one is a small dog, front feet pressed up against a balcony glassdoor or a large window. The perspective is from a little bit and to the side of the dog.

He’s looking across the distance at an apartment in the other skyscraper. It is filled with people at a party. They’re all talking and drinking and having a good time.

The dog is all by himself.

That’s a cartoon.

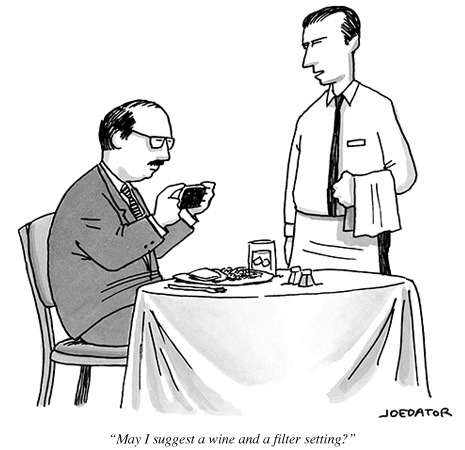

The one about suggesting a wine and a filter setting got a smile and a single chuckle from me…the rest are…’meh’

That’s one more chuckle than from me, but then I had to wade through a ton of those stoopid Instagram cartoons.

Really enjoyed your commentary. As a cartoonist I see that I fall into that trap of – one, wanting to be in the New Yorker, and two, emulating the style of the magazine. I need listen and act on my own voice more. So thank you. Great work and site.

[…] Ted Rall: […]

Alan Gardner makes me laugh. If anything is cheaper or stupider than the “sour grapes” argument, it’s going after someone who couldn’t possibly have sour grapes because he doesn’t apply to the New Yorker.

You’re an idiot. Why don’t you or other cartoonists “start” something of your own to show off what you, and other idiots think are “good” cartoons? So, everyone HAS to believe everything “60 Minutes” says? No one can think for themselves. Everyone is entitled to their opinion, it’s a pity so many people will read stupid ones like yours. Get a life.

You are so right. Why didn’t I think of that? Next time I receive a $20 million check for one of my cartoons, I will use it to start up my own magazine which I will then use to hire great cartoonists. About 60 minutes, again, you are totally right about my rampant idiocy. No one should expect the truth from a show that is said to be presenting news or journalism. That’s just silly! Everyone should not only think for themselves, but be able to imagine the truth out of thin air.

MMoosch,

No. Everyone is not entitled to their opinion. Everyone is entitled to an informed or a well-reasoned opinion. Everyone is entitled to demonstrate that they can participate in a discussion by presenting coherent arguments.

You haven’t done any of that. And, in actuality, very few people can actually “think” for themselves or for others. Usually what is done is “reaction” or mindless parroting. Again, back to the point about an informed opinion.

Ted’s opinion is informed by years and years of drawing and news critique/consumption.

Yours, apparently, is, um, “informed” by a sugar crash from too many Frosted Flakes. Calm down, eat some real food, get a nap, and then evaluate for the first time:

1. What you’re saying.

2. Whether it has any actual value.

I used to think I was the only one who didn’t get the gags, but I see it’s a common thing. After watching how the cartoons are chosen last week, I can only imagine that your work is chosen depending on which side of the bed Mankoff got out of that day.

I would argue that the ‘On the Internet…” is a valid cartoon, simply because it’s something that is true, but that a lot of people tend to forget. Many folks forget that an anonymous post, or blog under pseudonym, means you know nothing about the credentials or qualifications of the writer. They may by an actual expert with years of study; or they may just be regurgitating an opinion they heard somewhere else without any real understanding of what they’re saying. In short, they may actually be a dog; you don’t know.

But I agree overall with your assessment that the New Yorker is coasting on its reputation.

Ted,

Your point about learning to be a cartoonist by copying other cartoonists is amazing. Want to know the one universal truth about all good writers? ALL of them — I have never encountered a case where this isn’t true — read a LOT. When they start writing, almost always, they start by trying to make it “good” like ________ does. The blank being whomever the amateur’s favorite author is. After a while, a developing writer stops imitating the favorites and starts mixing and matching. So dialogue from Twain and Stout, character analysis from John D. MacDonald, narrative from Bradbury, etc.

Know how creative writing used to be taught? You started with something called “copywork.” A kid would be handed a poem or a passage, be told to read it, then copy it. This had two purposes: the kid learned how to write (cursive or block) and the kid learned how to write (how words come together). By the time you got to composition, you had first-hand experience with the basic frameworks. You could at least scrap something together that was okay. Now? Copywork is “boring” and “noncreative.” Bullshit.

I’ve never subscribed to the New Yorker. I have heard their comics praised, and I remember a few insightful or outright hilarious comics I’ve read in its pages over the years.

So, naturally, when I saw a coffee table book dedicated to New Yorker cartoons, I bought it immediately. What a letdown. When you pile them altogether like that the repetitiveness becomes obvious, as does the fact that very few of them actually are insightful or hilarious. You could just as easily compile random cartoons from random sources and come up with the same ratio of hilarious & insightful.

FWIW, Playboy cartoons show the same symptoms. They were absolutely hilarious when I was new to adulthood, but now I’ve seen most of the punchlines and am no longer titillated by the mere mention of tits. Maybe I’ve become jaded, maybe I’ve become sophisticated, or maybe I’ve just gotten older.

Whaaa, Whaaa, Whaaa! Like either of you schmoes know anything about me. $20million? Puh-leez. Bust your ass and get your stuff seen, if you get $20 million, or $2, good for you. You get what you deserve.

[…] The New Yorker is widely regarded the home of sophisticated cartoons and is a hugely competitive market for cartoonists. But Ted Rall is not a fan and argues that it is, in fact, bad for cartooning. […]