A century ago newspapers employed more than 2000 full-time editorial cartoonists. Today there are fewer than 25. In the United States, political cartooning as we know it is dead. If you draw editorial cartoons for a living and you have any brains you’re working in a different field or looking for an exit.

You can still find them online so political cartoons aren’t yet extinct. But they are doomed. Most of my colleagues are older than me (I’m 55). As long as there are people, words and images will be combined to comment on current affairs. But the graphic commentators of tomorrow will be ad hoc amateurs rather than professionals. They won’t have the income and thus the time to flesh out their creative visions into work that fulfills the medium’s potential, much less evolves into a new genre.

With zero youngsters coming up in the ranks and many of the most interesting artists purged, our small numbers and lack of stylistic diversity has left us as critically endangered as the wild cheetah. The death spiral is well underway.

June 2018: The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette fired Rob Rogers, a 25-year veteran, for drawing cartoons making fun of President Trump. (Rogers had always been a Democrat.)

January 2019: Steve Benson, the widely-syndicated winner of the Pulitzer Prize, was fired by the Arizona Republic after three decades of service.

May 2019: Gatehouse Media fired three cartoonists on the same day: Nate Beeler of the Columbus Dispatch, Rick McKee at the Augusta Chronicle and Mark Streeter at the Savannah Morning News.

June 2019: In one of the strangest offings, the New York Times fired both of its cartoonists, Heng and Patrick Chappatte, in order to quell criticism over a syndicated cartoon—one drawn by an entirely different cartoonist. The Syrian government thugs who smashed Ali Ferzat’s hands with a hammer in 2011 were more reasonable than editorial page editor James Bennet; the goons only went after the actual cartoonist whose cartoons offended President Bashar Assad. Nor, by the way, did the Syrian dictator ban all cartoons. Political cartooning is now and forever banned from the 100%-censored Times.

And of course in 2015 the Los Angeles Times, whose parent company had recently been purchased by the Los Angeles Police Department pension fund, fired me as a favor to a prickly police chief because he was angry at my cartoons. In 2018 the same paper fired cartoonist David Horsey for the crime of accurately describing White House press flak Sarah Huckabee Sanders’ looks as those of a “slightly chunky soccer mom.” As at a Stalin-era show trial, they forced Horsey to apologize before giving him the boot.

Individual cartoonists are under fire around the world. Only in the United States, “land of the free,” has the art form as a whole been targeted for systematic destruction by ruling elites and cultural gatekeepers. After decades of relentless, sweeping and never-reversed cutbacks there are now far more political cartoonists in Iran than in the United States. After terrorists murdered 12 people at Charlie Hebdo, a single publication in France, hundreds of U.S. newspapers ran editorials celebrating the power of cartoons; 99% of these hypocritical blowhards didn’t employ a single cartoonist.

American editorial cartooning didn’t just die. It was murdered.

Here’s how it happened/it’s happening:

Cartoonists were overrepresented in mass layoffs. Publishers fired numerous journalists. But they always came first for the cartoonists.

Scab syndication services undercut the market. A few discount syndication companies, one in particular, sold bulk packages of heavily discounted hackwork, undercutting professionally-drawn cartoons.

Publishers killed the farm system. The early 1990s marked the start of a vibrant new wave of “altie” political art by Generation Xers. Urban free weeklies carried our work but deep-pocketed dailies and magazines refused to hire us. Gifted young cartoonists realized they’d never be hired and abandoned the profession.

Social media mobs spook editors. Twitter and Facebook make it easy for six angry dorks to look like thousands of angry readers ready to burn down a newspaper over a cartoon. Cowardly editors comply and sack their artist at the request of people who don’t subscribe to the paper.

Prize committees reward(ed) bland cartoonists. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Alties like Tom Tomorrow, Andy Singer, Clay Butler, Ruben Bolling, John Backderf and Lloyd Dangle were reinventing American political cartooning. Their revolution would not be recognized. The Pulitzer Prize committee snubbed alties. (Though some have been finalists—me in 1997—no altie has won a Pulitzer.) Among the older traditional cartoonists as well, prizes usually went to safe over daring. Awards signal what’s acceptable and what’s not. Editors pay attention. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle.

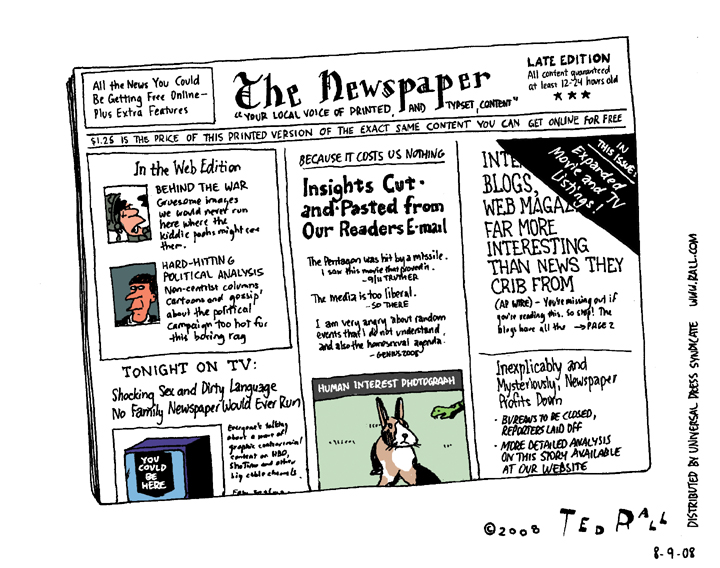

Legacy employers blackballed edgy cartoonists. Click data proves that controversy is popular. Faced with shrinking circulation, however, print newspapers and magazines played it safe and avoided controversy. Kowtowing to advertisers rather than the readers who drive circulation, publishers fired the controversial cartoonists—the ones whose work readers were talking about—first. Another self-fulfilling prophecy: the dull cartoons Americans saw in major outlets like USA Today elicited little response from readers. They weren’t missed after they vanished.

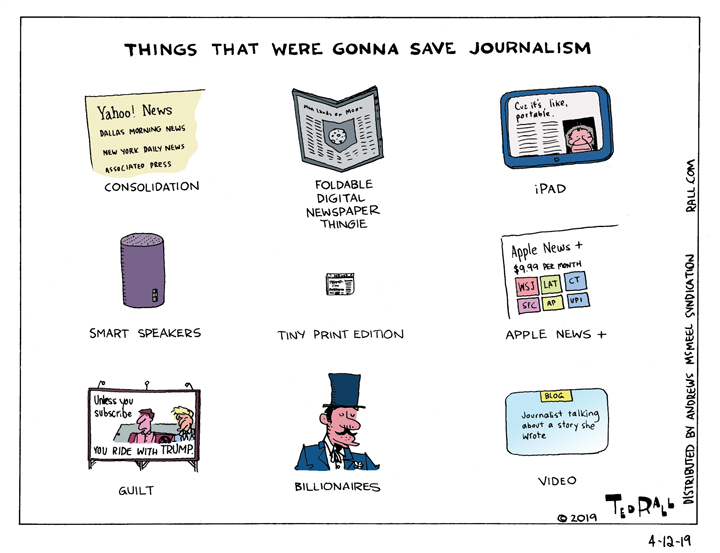

Billionaire newspaper “saviors” refuse to hire cartoonists. When billionaires buy papers they invest in reporters and editors. Not cartoonists. One exception is Sheldon Adelson, who hired Mike Ramirez at the Las Vegas Review-Journal. But 90% of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway-owned newspapers employ zero cartoonists. Patrick Soon-Shiong bought the LA Times after they fired Horsey and me; his paper hired a bunch of underpaid Millennial writers but never replaced or brought back the two cartoonists. To his credit Jeff Bezos kept Tom Toles and Ann Telnaes on at the Washington Post, but he hired “dozens of reporters”—and no one new to draw cartoons. (Historically many newspapers have employed multiple cartoonists.)

Twee identity-politics cartoons are boring. Boosters sometimes point to sites for Millennial cartoonists as a bright spot. For the most part, these cartoons are flat, preachy and predictable. Right or left, political correctness is death to political cartooning.

Online media sites refuse to hire cartoonists. News sites like Huffington Post, Salon, Slate and Vox are heirs to print newspapers. None employ cartoonists. Don’t they realize theirs is a visual medium?

Cartoonists fulfill the market for crappy cartoons. Editors, publishers and award committees have made clear what kind of cartoons they are most likely to buy and reward. Jokes should be conventional, preferably derivative. Sacred cows must not be criticized. Patriotism is mandatory. Artistic styles remain frozen safely in the 1960s, when most editors were kids. Cartoonists have a choice: give the marketplace what it wants or go hungry. Many cartoonists produce work they know is beneath their talents, readers don’t react when they appear in print and no one takes note when the cartoonist gets laid off.

I love editorial cartooning. All I ever wanted to do was draw for a living. When I was growing up, political cartooning was clever and dangerous. Punk rock.

Now it’s Muzak.

Muzak is dead.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of “Francis: The People’s Pope.” You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)