When the going gets less tough, Americans get stupid.

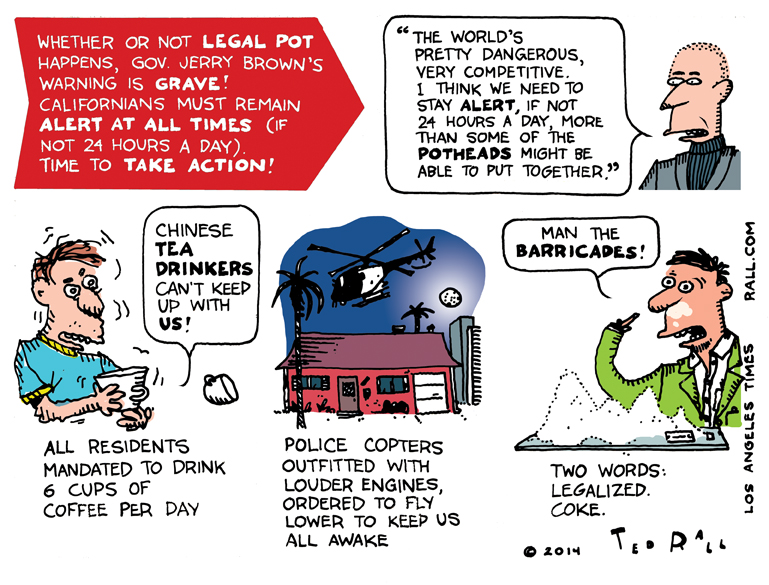

Stupid means big. During economic booms — or times like now, when the economy still sucks but sucks somewhat less than before — automakers crank out giant gas guzzlers. And homebuilders build huge.

Big doesn’t have to mean ugly (viz, the Taj Mahal). But it usually does.

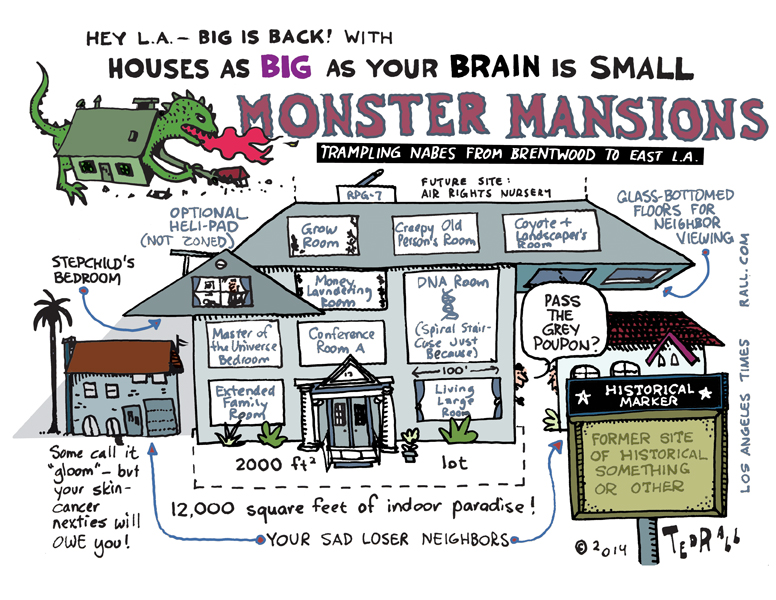

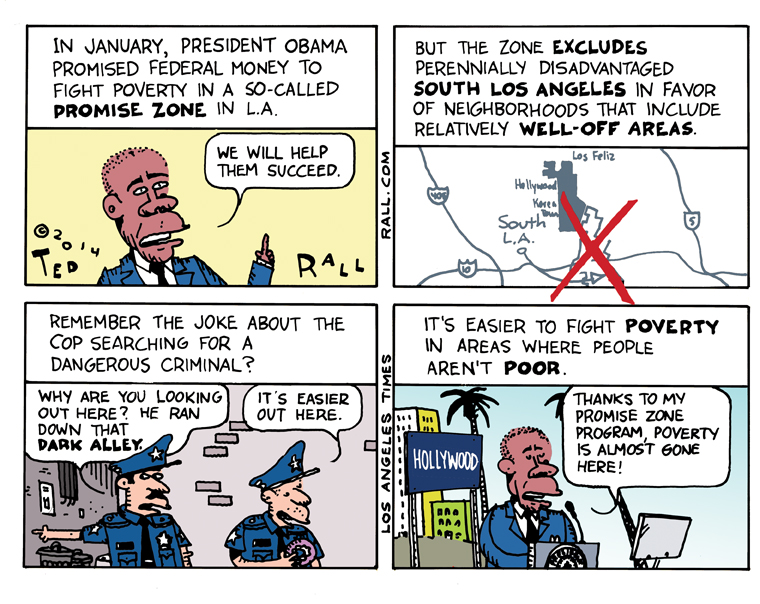

Los Angeles still has a whopping 11.3% unemployment rate, significantly worse than the already high statewide average of 8.9%, but lower than before. And so, with a whiff of pseudoprosperity in the fiscal air, real estate developers are bringing back McMansions — gargantuan monstrosities that dwarf not just their neighbors’ older homes, but also their own plots of land.

Garage mahals. Starter castles. Hummer houses. If you build one, your neighbors may or may not come. (Based on that privet, you may not want them to.) But they will sneer.

Biggification is a national trend. “Nearly 40% of new homes built last year had four or more bedrooms, a return to the all-time high reached in 2005 and 2006. And nearly 20% have three-car garages, an increase following two years of declines,” Time reported in 2012.

“Builders are snapping up smaller, older homes, razing them and replacing them with bigger dwellings. Increasingly, sleek, square structures are popping up along streets known for quaint bungalows,” Emily Alpert Reyes reports in the Times.

Reyes points to a 3,000-plus square feet spec house on a block in Hollywood where most homes run 2,000 square feet. It’s out of place, it annoys the neighbors, but under L.A. zoning rules, it’s all completely legal. “If the city code allows it, and you want a bigger house, you have the right to a bigger house,” says Amnon Edri, the developer. “This is America. It’s a free country.”

Too bad, that.

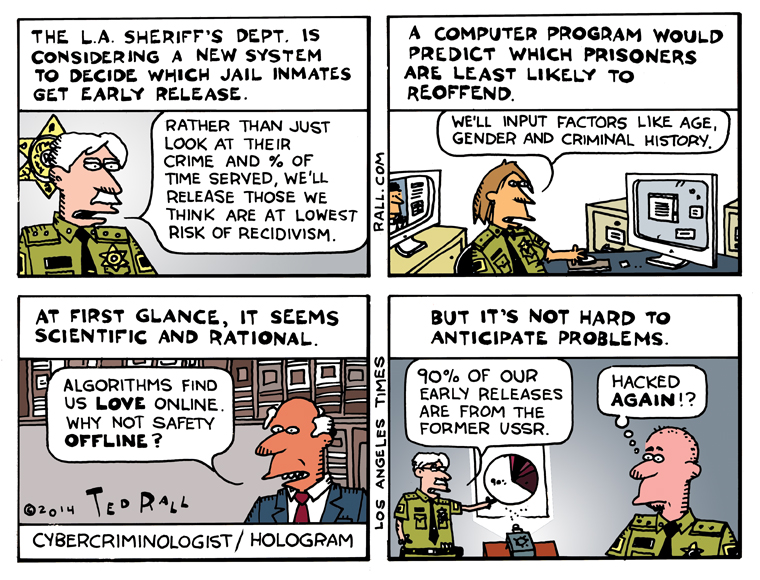

The Baseline Mansionization Ordinance of 2008 was supposed to rein in developers’ drive to build bigger and uglier. But the loopholes are big enough to park two Denalis and a Chevy Suburban:

Builders can get a bonus to build 20% or 30% larger than ordinarily allowed if they design their homes to be environmentally friendly, or if they adhere to certain scaling requirements of home facades and upper floors. The home Edri is building on Stanley Avenue, for example, was allowed hundreds of feet of additional floor area because part of the facade was recessed, according to its building permit.

Critics point out that some construction that can bulk up the appearance of residences isn’t counted against the size limits. Up to 400 square feet of “covered parking area” can be excluded from city calculations, for example.

Architects, real estate brokers and developers complain that restrictions on home sizes, such as those passed last year in Beverly Grove, have stifled their ability to accommodate customers’ desires: “Architect Daniel Bibawi said that since the tighter Beverly Grove building limits were approved last year, his firm hasn’t had any projects in the area. The families that hire him typically want at least five bedrooms to accommodate two children, a master bedroom, a guest room and an office, he said.”

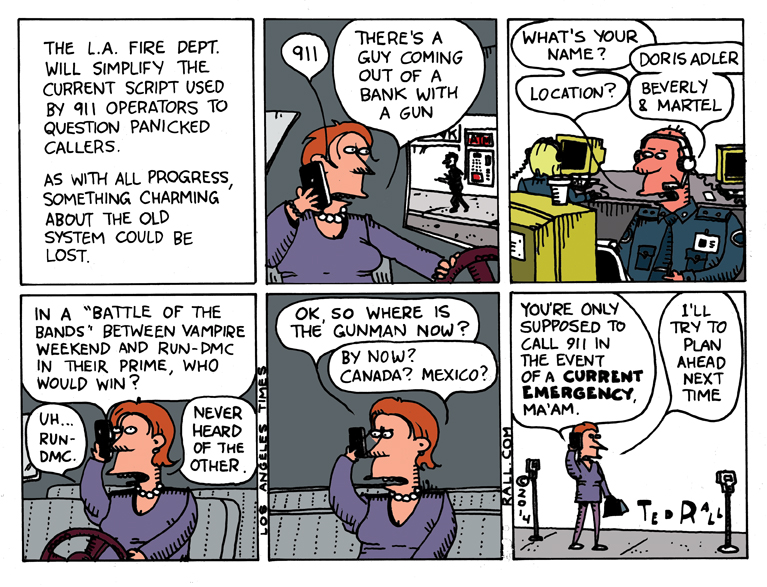

My main objection to McMansions is that they, like most post-1960s architecture, are made not just of ticky-tacky but of pure fugly. My eyes! They burn!

But there are serious objections on, among other things, environmental grounds. Thomas Frank, known for his why-do-poor-people-vote-Republican? book “What’s the Matter with Kansas?”, has a grand theory of How McMansions Make Everything Suck that’s worth quoting in its entirety:

This [McMansion] is [American] civilization’s very center, the only thing that really makes sense in ‘clusterf— nation,’ the tawdry telos at which all our economic policies aim. Everything we do seems designed to make this thing possible. Cities must sprawl to accommodate its bulk, eight-lane roads must be constructed, gasoline must be kept cheap, coal must be hauled in from Wyoming on mile-long trains. Middle-class taxes must be higher to make up for the deductions given to McMansion owners, lending standards must be diluted so more suckers can purchase them, banks must be propped up, bonuses must go out, stock prices must ascend. Every one of us must work ever longer hours so that this millionaire’s folly can remain viable, can be sold successfully to the next one on the list. This stupendous, staring banality is the final outcome for which we have sacrificed everything else.

They do make for cartoons that are fun to draw, though.