The Case for Shiftlessness

No bank balance. Nothing in your wallet.

“I’m broke,” you say. “I need a job.”

Or:

Perhaps you have a job. Then you say:

“I’m broke. I need a better job.”

You’re lying. And you don’t even know it.

You don’t need a job.(Unless you like sitting at a desk. Working on an assembly line. Non-dairy creamer in the break room. In which case I apologize. Freak!)

You don’t need a job. You need money.

We’ve been programmed to believe that the only way to get money is to earn it.

(Unless you’re rich. Then you know about inheritance. In 1997, the last year for which there was solid research done on the subject, 42 percent of the Forbes 400 richest Americans made the list through probate. Disparity of wealth has since increased.)

It’s time to separate income from work.

For two reasons:

It’s moral. No one should starve or sleep outside or suffer sickness or go undereducated simply due to bad luck—being born into a poor family, growing up in an area with high unemployment, failing to impress an interviewer.

It’s sane.

“American workers stay longer at the office, at the factory or on the farm than their counterparts in Europe and most other rich nations, and they produce more over the year,” according to a 2009 U.N. report cited by CBS. Thanks to technological innovations and education, worker productivity—GDP divided by total employment—has increased by leaps and bounds over the years.

U.S. worker productivity has increased 400 percent since 1950. “The conclusion is inescapable: if productivity means anything at all, a worker should be able to earn the same standard of living as a 1950 worker in only 11 hours a week,” according to a MIT study.

Obviously that’s not the case. American workers are toiling longer hours than ever. They’re not being paid more —to the contrary, wages have been stagnant or declining since 1970. Numerous analyses have established that, especially since 1970, the lion’s share of profits from productivity increases have gone to employers.

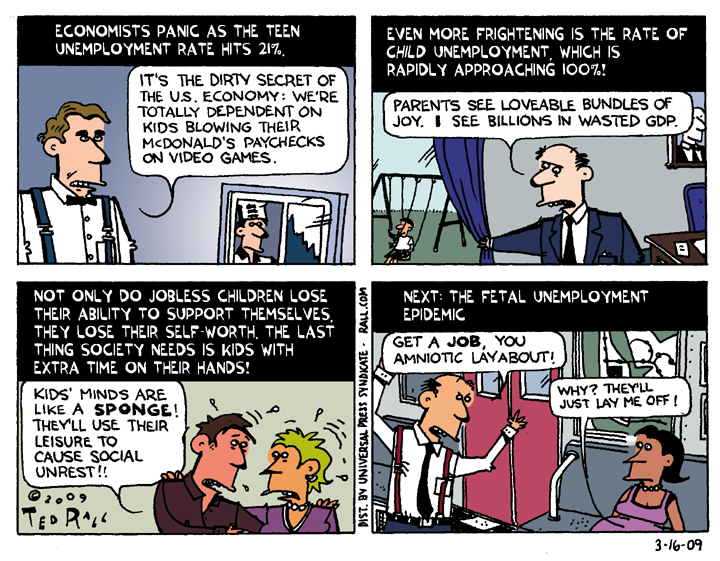

Workers are working longer hours. But fewer people are working. Only 54 percent of work-eligible adults have jobs—the lowest rate in memory. Which isn’t surprising. Because there are fixed costs associated with employing each individual—administration, workspace, benefits, and so on—it makes sense for a boss to hire as few workers as possible, and to work them long hours.

This witches’ brew—increased productivity coupled with higher fixed costs, particularly healthcare—have led companies to create a society divided into two classes: the jobless and the overworked.

Unemployment is rising. Meanwhile, people “lucky” enough to still have jobs are creating more per hour than ever before and are forced to work longer and harder.

Crazy.

And dangerous. Does anyone seriously believe that an America divided between the haves, have-nots and the stressed-outs will be a better, safer, more politically stable place to live?

Sci-fi writers used to imagine a future in which machines did everything, where people enjoyed their newfound leisure time exploring the world and themselves. We’re not there yet—someone still has to make stuff—but we should be closer to the imagined idyll of zero work than we are now.

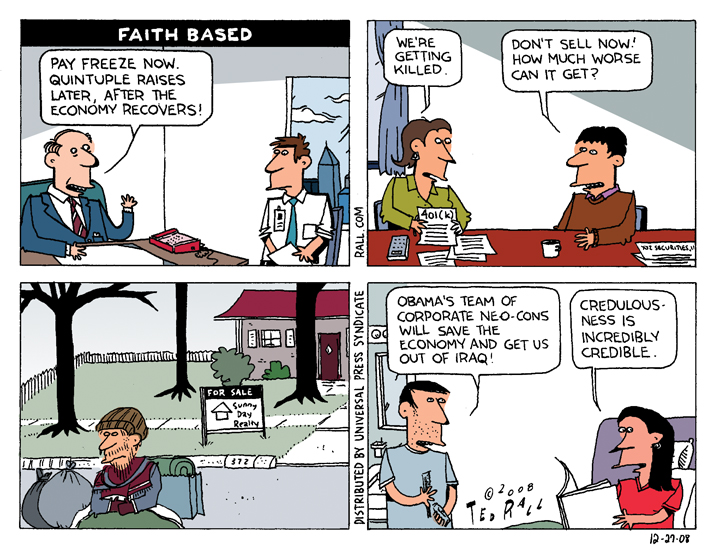

If productivity increases year after year after year, employers need fewer and fewer employees to sustain or expand the same level of economic activity. But this sets up a conundrum. If only employees have money, only employees can consume goods and services. As unemployment rises, the pool of consumers shrinks.

The remaining consumers can’t pick up the slack because their wages aren’t going up. So we wind up with a society that produces more stuff than can be sold: Marx’s classic crisis of overproduction. Hello, post-2008 meltdown of global capitalism.

Silicon Valley entrepreneur Martin Ford warns that the Great Recession is just the beginning. In his 2009 book “The Lights in the Tunnel: Automation, Accelerating Technology and the Economy of the Future” Ford, “argues that technologies such as software automation algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI), and robotics will result in dramatically increasing unemployment, stagnant or falling consumer demand, and a financial crisis surpassing the Great Depression,” according to a review in The Futurist.

The solution is clear: to guarantee everyone, whether or not he or she holds a job, a minimum salary sufficient to cover housing, transportation, education, medical care and, yes, discretionary income. Unfortunately, we’re stuck in an 18th century mindset. We’re nowhere close to detaching money from work. The Right wants to get rid of the minimum wage. On the Left, advocates for a Universal Living Wage nevertheless stipulate that a decent income should go to those who work a 40-hour week.

Ford proposes a Basic Income Guarantee based on performance of non-work activities; volunteering at a soup kitchen would be considered compensable work. But even this “radical” proposal doesn’t go far enough.

Whatever comes next, revolutionary overthrow or reform of the existing system, Americans are going to have to accept a reality that will be hard for a nation of strivers to take: we’re going to have to start paying people to sit at home.

(Ted Rall’s next book is “The Book of Obama: How We Went From Hope and Change to the Age of Revolt,” out May 22. His website is tedrall.com.)

COPYRIGHT 2012 TED RALL