Responding to polls that show that voters are worried and angry about the high cost of housing, both major parties are floating plans to make buying a home more affordable. Harris and the Democrats want to encourage new housing construction and subsidize first-time home buyers by $25,000, which economists worry would have an inflationary effect. Trump thinks that deporting illegal immigrants would reduce demand and lower prices—a logical stretch to say the least.

Responding to polls that show that voters are worried and angry about the high cost of housing, both major parties are floating plans to make buying a home more affordable. Harris and the Democrats want to encourage new housing construction and subsidize first-time home buyers by $25,000, which economists worry would have an inflationary effect. Trump thinks that deporting illegal immigrants would reduce demand and lower prices—a logical stretch to say the least.

As important as it is to allow middle-class and working-class people to build wealth by investing in a house or condo, however, the real need is not those who would prefer to own than to rent their residence. The real need is those who have no housing at all.

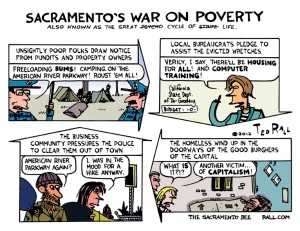

Roughly half a million Americans are chronically homeless and nearly four million more “hidden homeless” are imposing on friends and family for a place to stay that may or may not remain available in the future. Cities are blighted, families are shattered, children are traumatized. Homelessness is both a moral and economic crisis as well as a failure of leadership.

Homelessness impacts us all. Every person who must be treated at the emergency room as a consequence of going unhoused not only burdens the healthcare system, they live outside the workforce who contribute to productivity, fuel consumer spending and remit payroll taxes. Their deprived physical persons, their meager possessions and their vehicles are eyesores that negatively impact property values and thus reduces municipal revenues. People experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity get arrested more often than the average citizen, only for survival offenses like stealing food and clothing. Many are or become mentally ill, especially from schizophrenia, as a result of fending off hot and freezing weather; homeless people commit about thirty times more violent crimes than average.

According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, it would cost about $55 billion, most of it spent once rather than recurring, to house both the visible and hidden homeless, who total about 4.5 million people. But where would we put all these people?

Incredibly, that answer is easy. There’s no need to build a single new unit. We have plenty lying around completely unused.

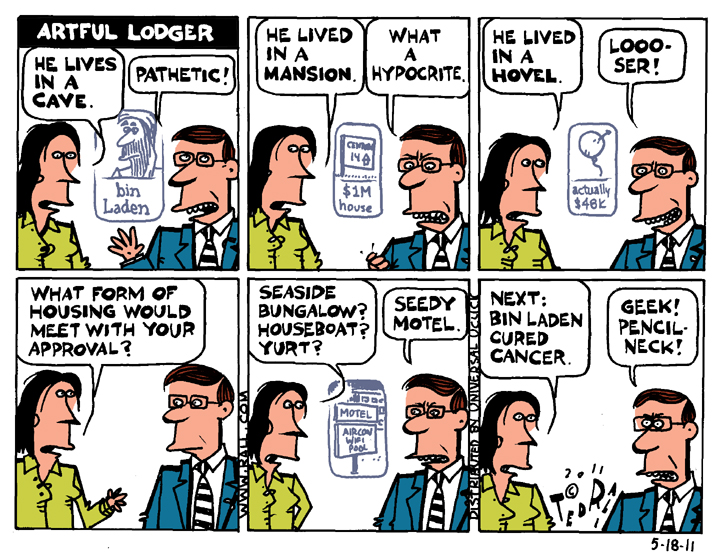

More than 15 million homes, over 10% of the nation’s housing stock, was vacant in 2022—a record low. Three out of four are investment properties, many owned by venture-capital companies that are converting neighborhoods once comprised of local homeowners into transient rental units with algorithmically-inflated rents, particularly in middle-class areas with many people of color. Most of these are vacation homes, timeshares and hunting cabins that sit empty well over 95% of the year.

Property rights matter, but a national emergency like a war prompts the government to requisition private property in service to an important cause. During World War II, for example, the United Kingdom commandeered personal cars and paid their former owners what they determined to be fair market value, while the United States requisitioned merchant ships. U.S. occupation forces appropriated German land for military use in the late 1940s.

Homelessness is a national emergency on par with World War II. Actually, it’s much bigger. Had the isolationists prevailed and the U.S. not joined the Allies against Japan and Germany, there is no reason to believe that the U.S. itself would ever have been invaded. For America, World War II was optional. Fighting homelessness is about saving the lives of millions of American citizens right here at home. It’s as essential as it gets.

Florida and Hawaii, both popular vacation destinations, have more vacant second homes than other states. But the vacation-house mentality also afflicts cities with high densities—or that used to have them. In the 2005-2009 American Community Survey, 102,000 of the 845,000 apartments and houses in Manhattan were identified as vacant. One out of 25 units in the nation’s cultural, media and financial capital were occupied less than two months out of the year. “In a large swath of the East Side [of Manhattan] bounded by Fifth and Park Avenues and East 49th and 70th Streets, about 30% of the more than 5,000 apartments are routinely vacant more than ten months a year because their owners or renters have permanent homes elsewhere,” The New York Times reported in 2011. It’s worse now.

The number of vacant units in New York City lines up almost exactly with the estimated number of homeless men, women and children: 100,000.

Every single person who shivers on the sidewalks of the Big Apple does so within a few dozen feet of a heated, insulated, empty apartment with running water, a place that no one uses. It’s obscene. It’s piggish. And it needs to be fixed. A real estate speculator’s right to invest in a housing market is not half as important as a homeless person’s need to sleep inside. A bourgeois family’s desire to winter in Florida and summer in New York must take a back seat to the human right of a homeless person not to die.

City and state housing authorities should be granted the right and the funding appropriations necessary to seize vacant housing units under eminent domain for conversion to housing for the homeless, with fair market compensation to be paid to those deprived of their properties.

The United States signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which recognizes housing as a basic human right, in 1948. The UDHR was codified into a treaty, the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights in 1966. Because the U.S. signed the ICESCR, it is obligated to uphold its “object and purpose.” Nearly eighty years after our nation committed to ensuring that everyone has a decent and secure place to live where he or she need not fear eviction, it should make good on its commitment to international law.

Condemn vacant investment properties and vacation homes and seize them under eminent domain.

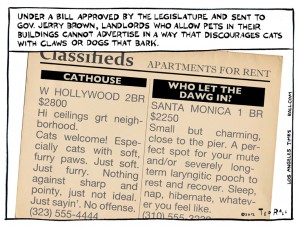

Until the last American citizen moves from the outdoors to the indoors, no one should be legally permitted to own more than one home.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. His latest book, brand-new right now, is the graphic novel 2024: Revisited.)

The U.S. government wastes approximately $4.5 trillion each year. “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking real money,” Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen, an Illinois Republican, famously said, and said often. In this case, you’re talking about thousands of billions. ($4.5 trillion is the sum total of annual military spending that exceeds what we need to defend the United States homeland, the higher interest paid on the national debt due to the Fed’s attempts to fight inflation, federal subsidies paid to people and companies who don’t qualify for them, uncollected taxes the IRS doesn’t even attempt to get and foreign aid, much of it to rich countries.)

The U.S. government wastes approximately $4.5 trillion each year. “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking real money,” Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen, an Illinois Republican, famously said, and said often. In this case, you’re talking about thousands of billions. ($4.5 trillion is the sum total of annual military spending that exceeds what we need to defend the United States homeland, the higher interest paid on the national debt due to the Fed’s attempts to fight inflation, federal subsidies paid to people and companies who don’t qualify for them, uncollected taxes the IRS doesn’t even attempt to get and foreign aid, much of it to rich countries.)