Originally published by ANewDomain.net:

“When did Americans decide that allowing our kids to be out of sight was a crime?” asks a mom in the northern suburbs of Washington DC whose husband was threatened with arrest by child welfare agents who said they would take away their kids – for the “crime” of allowing their 10-year-old son to walk home free of adult supervision from a nearby public park.

Danielle Meitiv cites other examples of what appears to be a growing trend: the criminalization of free-range childhood. In the Washington Post, Meitev writes:

Last summer, Debra Harrell of North Augusta, S.C., spent 17 days in jail because she let her 9-year-old daughter play at a park while she was working. In Port St. Lucie, Fla., Nicole Gainey was arrested and charged with neglect because her 7-year-old was playing unsupervised at a nearby playground, and Ashley Richardson of Winter Haven, FL, was jailed when she left her four kids, ages 6 to 8, to play at a park while she shopped at the local food bank.”

Lenore Skenazy sparked controversy with a 2008 New York Times essay bearing the self-explanatory title “Why I Let My 9-Year-Old Ride the Subway Alone.”

“Was I worried? Yes, a tinge,” Skenazy admitted. “But it didn’t strike me as that daring, either. Isn’t New York as safe now as it was in 1963? It’s not like we’re living in downtown Baghdad.”

“Was I worried? Yes, a tinge,” Skenazy admitted. “But it didn’t strike me as that daring, either. Isn’t New York as safe now as it was in 1963? It’s not like we’re living in downtown Baghdad.”

Actually, in downtown Baghdad, kids are everywhere.

How old must a child be to be left alone at home? Only five states set a legal limit. (I wonder how many Illinois parents know they are risking child endangerment charges by trusting their 13-year-old not to burn down the house?) As a guideline, experts currently say that, while it depends on the psychological maturity of the child, 7 to 10-year-olds can handle short periods on their own and that kids over age 12 can go a whole day but nevertheless shouldn’t be left home overnight without an adult at home.

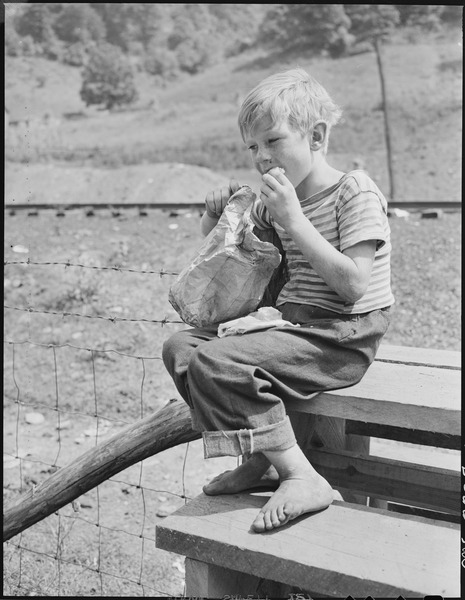

To answer Meitiv’s question, there appears to have been a major transformation during the 1990s and 2000s in attitudes about balancing the competing concerns of keeping kids safe and fostering the independence necessary to mature into adulthood.

Growing up in a suburb of Dayton, Ohio to the 1970s, I remember adults were downright cavalier about children. Starting in third grade, I walked to and from school in all kinds of weather. It was two miles each way, a significant distance on those short little legs, especially during an ice storm. (School superintendents were stingier with snow days back then.)

I rode my bike all over town, especially during the summer to the swimming pool, which was about a seven-mile round-trip. My mother wasn’t especially neglectful; every kid I knew carried, as I did, a pocket full of dimes for a pay phone in case they got in trouble.

The irony is that back then, when parents were running off to “key parties” and letting their kids be babysat by “Gilligan’s Island” reruns, it was a far more dangerous time to be a child in America than it is now, when local law enforcement is cracking down on people who refuse to be helicopter parents.

Street crime has plummeted since when I was a kid in the 1970s. It’s not like predators were snatching children off the streets all the time, but it wasn’t unheard of. Twice before turning 16, sketchy men tried to lure me into their cars. A mile up Route 48, the same street where I walked to high school every morning, a serial killer kidnapped, raped and murdered a 14-year-old girl going to her own school. Most kids from the 1970s generation have a story like that, one or two degrees of separation removed.

That’s not the case now.

Of course, if you are a would-be child killer, it’s going to be pretty difficult to satisfy your bloodlust in a society where you never see kids walking the streets.

Keeping kids safe is a parent’s primary responsibility. People my age – I’m 51 – ruefully recall feeling like no one cared about our safety when we were children. We shouldn’t return to that era. But parents have another, equally important duty: turning their kids into grown-ups.

How the hell are today’s kids going to become the adults of tomorrow?

When I was nine years old, my mom let me take the city bus downtown to Dayton’s edgy urban core. I have to think that familiarizing myself with mass transit slowly, during my teenage years in a smaller city, made it easier for me to transition to the New York City subway, which I had to figure out at the age of 18 as a student at Columbia University.

Similarly, although sometimes I worried that my mother had gotten into a car accident when she ran late at work, it was a good experience to learn, again over time, that 99% of the time there’s nothing to fear even when you are afraid. Besides, being left home alone today would have been a less fraught experience thanks to text messaging and cellular phones.

By the time I was 15 years old, I had a pretty good sense of direction. We didn’t have Google Maps, but we had the printed kind, and the experience of driving around and sometimes getting lost, so we soon had a strong sense of where things were and how to get there. You need that as an adult. As I watch my friends shuttle their kids around by car, I always wonder, how can these children – who have absolutely no reason to know or care where they are being taken or how it fits into context – make the jump into fully realized independent adulthood?

“The pendulum has swung too far,” Meitiv wrote, and I agree. “We need to take back the streets and parks for our children. We need to refuse to allow ourselves to be ruled by fear or allow our government to overrule decisions that parents make about what is best for their children.”

This being America, it’s probably going to take a bunch of legal battles in the form of parents fighting back against out-of-control child welfare authorities — who in 45 states are “enforcing” non-existent laws — to restore some sense of sanity. In the meantime, we are engaged in a social struggle that will determine whether the first totally online/totally protected generation of American children somehow manage to develop into viable adults.