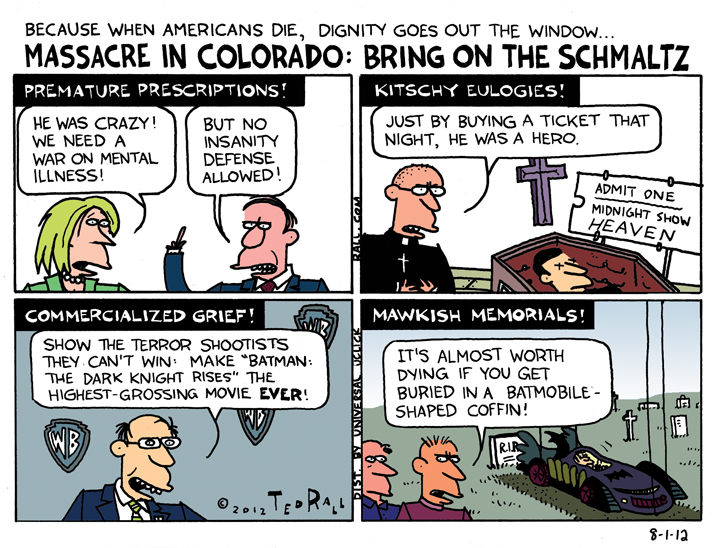

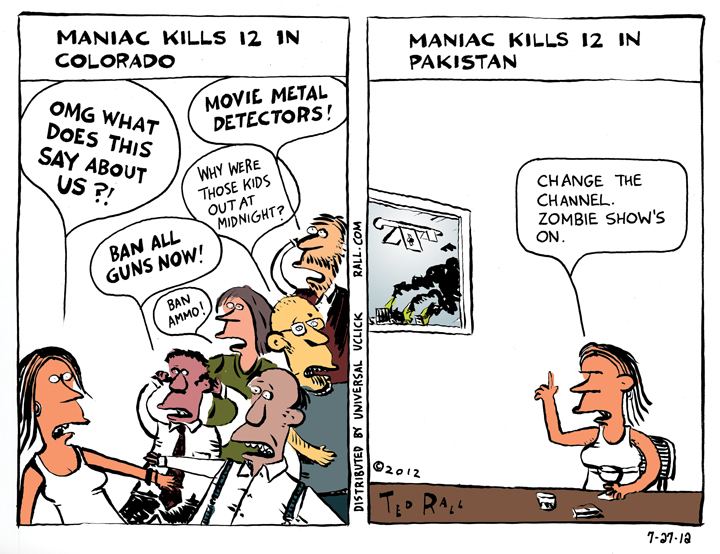

Mass shootings prompt simple explanations of the gunman’s motivation. At Columbine High School in Colorado, the killers supposedly snapped after being bullied. The guy who shot up a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado was wild-eyed carrot-topped nuts. After a massacre at a Walmart in El Paso, an anti-immigrant manifesto posted online pointed to right-wing politics. Simple mental illness—if there is such a thing—appears to be the culprit in Dayton, Ohio. Also misogyny. But the Dayton shooter’s Twitter feed indicates the shooter liked Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. So right-wing media blames his progressive leanings.

And when there is no obvious explanation as in Las Vegas in 2017, when the mass murderer doesn’t leave a final message and doesn’t appear to have subscribed to extremist politics and was financially secure, but drank a lot and may have bought into Internet conspiracy theories, we shrug our shoulders and forget about it. But deep inside we believe there is a simple answer. We just haven’t discovered it yet.

Gun control advocates want to ban assault rifles like the semi-automatic AR-15 used in so many mass shootings. But even if those guns disappeared overnight, gun-related massacres would still occur, albeit with lower body counts. Which would be nice, but it wouldn’t address the big question, the one we secretly ask ourselves after such incidents: where does the rage come from?

Flailing about in search of the enablers of personal mass violence (as opposed to state-ordered mass violence) is useful as far as it goes. The NRA and the gun lobby make money with every firearm purchase. Victims of mental illness go uninsured and thus undiagnosed and untreated. Hateful rhetoric, most common on the right and most recently epitomized by President Trump, legitimize the dehumanization of future victims.

In the beginning, though, is rage.

The blind anger that, like the medieval image of a succubus insinuating itself into a previously healthy brain, suggests that shooting a lot of people is either a solution or at least a satisfying way of venting, is the germ of the idea that leads to the first shot being fired at a military base, an elementary school, a country music concert.

The rage says: “I hate everybody.” It continues: “I wish everyone would die.” It concludes: “I will kill them all.”

I am mystified by the fact that so many people are mystified about rage.

I have been there. I have hated everyone. I have been so depressed that I didn’t care what happened to me. I was furious at how oblivious everyone was to my pain and how nobody cared about me. I wanted them to pay for it. Haven’t you ever felt that way?

Mostly it was when I was younger. In junior high school, when I was relentlessly bullied and beaten up and neither my classmates nor my teachers interfered—to the contrary, they thought it was funny—I fantasized about going to school and shooting everyone there.

When I was a junior in college, I spent finals week at the hospital due to a freak injury. Several of my professors refused to allow me to take a make-up exam because they were lazy, I got Fs and landed on academic probation, and the following semester one mean teacher gave me a C+ and so I got expelled. I lost my job, my dorm room and thus a place to live and wound up homeless on the streets of New York. Watching people go about their day, smiling and laughing and exchanging pleasantries and buying luxuries while I was starving, I despised them. Of course it wasn’t their fault. I knew that. What was their fault, in my view at the time, was their active decision not to engage in the struggle for a world that was fair and just, not just to me, but to everybody.

I imagine that most, if not all, homeless people feel that way watching me stroll down the street on my stupid smartphone. They hate me and they are right to hate me.

The NRA and the weapons business and Congress share responsibility, but what really causes mass shootings is the shooters’ alienation from society.

Why doesn’t America enforce mental health insurance parity? Because the American people don’t care enough to raise enough hell to force our elected officials to do so. If you have ever been broke and needed to see a therapist, you probably found out that they charge at least $200 an hour and that your insurance company probably won’t cover it—assuming that you have insurance. American society’s message to you is loud and clear: we don’t care about you. Go ahead and be insane. Die. Returning society’s contempt for you is perfectly understandable.

The so-called “incel” (involuntarily celebate) movement of men who hate women because they won’t sleep with them is a perfect example of society’s refusal to try to understand a legitimate concern. In 2014 an incel killed six people near Santa Barbara. “I don’t know why you girls aren’t attracted to me, but I will punish you all for it,” the killer said in a video he posted before his rampage. In 2018 an incel killed 10 people in Toronto with his van.

Experts recommend writing laws to deny incels access to guns, shutting down their online forums so that they don’t work each other up, and improving their access to mental health care. Those may be good ideas. But they ignore the root of the problem.

Obviously no one has to have sex with anyone. Incels don’t have a constitutional right to get laid. But anyone who has ever been young and sexually frustrated (or old and sexually frustrated) knows that sexlessness can literally drive you crazy. Glibly suggesting to awkward or clueless or physically unattractive men to hit the gym and get their charm on is just as hopelessly naïve as Nancy Reagan’s “just say no” campaign. Feeling condemned to a life without love or physical companionship really truly sucks and we could start by acknowledging that.

Rage, I think, comes less from having a problem that feels hopelessly unsolvable than from the belief that no one gives a damn about you or your issues. People need to feel heard. People need to be heard.

Given how callous and unfeeling we are about so much suffering around us and among us, the only thing surprising about mass shootings is that they don’t happen more frequently.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of “Francis: The People’s Pope.” You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)