How to respond to Kanye West? His business partners severed ties. Liberal media outlets resorted to cancel culture. Elon Musk gave the artist now known as Ye a second chance on Twitter, only to regret his magnanimity after Ye posted a graphic of a swastika intertwined with a star of David, and kicked him back off the platform.

The freak show that kicked off with Ye’s 2018 Oval Office meeting with President Donald Trump—a moment whose strangeness was reminiscent of Nixon Meets Elvis—culminated over the last two months with, among other acts, Ye’s bizarre donning of a White Lives Matter shirt, anti-Semitic threats on Twitter, hanging out with a white nationalist and praising Hitler and the Nazis during a video appearance with Alex Jones.

I’m not a psychologist but you don’t have to be a mental health expert to see that Ye is suffering from some sort of personality disorder or illness that is causing or contributing to this former billionaire’s public decompensation. We know that he suffered from depression after the 2007 death of his mother and has been formally diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which causes extreme mood swings. When someone is in the throes of a psychological crisis, responding politically subjects someone who ought to get help to punishment instead—punishment that can only exacerbate their pain.

Trevor Noah suggested that Ye needs to be “counseled, not canceled.” But how?

As a leftist I’m hardly predisposed to sympathizing with a billionaire who expresses loathsome racist and bigoted political views. Nor do I often agree with the point of view of corporations like Adidas, Balenciaga, Gap and Creative Artists Agency (CAA), all of which cut ties with the troubled rapper. But these companies can hardly be faulted for trying to protect their brands.

Yet I have even less sympathy for liberals and progressives who take to their opinion columns to pompously approve of the dismantling of this man’s life and career. Where is their compassion? “If the culture averted its gaze from his indiscriminate bluster, what would be the loss?” Robin Givham asked in The Washington Post. To me personally, nothing at all. I don’t listen to Ye’s music. That’s not the point.

Because he is a human being in crisis, Ye deserves sympathy. Because celebrities and the way we treat them trickles down, his pitiful situation matters to the rest of us.

Society suffers when we don’t live up to liberals’ oft-stated declarations that we should sympathize with people who struggle because the organ that is broken happens to be their brain as opposed to, say, their lungs or their liver. If you saw a woman fall and break her leg, you would stop and help her. Watch the same woman curse at someone who isn’t there, and you avert your eyes and hasten by.

Yet judging that woman is self-destructive: any of us might lose our mind. All it takes is a shift in the chemical balance between your levels of dopamine and serotonin.

Criminal courts and common people rightly consider mental state and motivation when assessing guilt or innocence, and, if guilt is found, severity of punishment. The tricky question is: is Ye anti-Semitic, crazy or both?

After a drunken Mel Gibson went on an anti-Semitic rant after being pulled over by a police officer, he explained that he had “said things that I do not believe to be true and which are despicable.” But thoughts and opinions don’t come out of a vacuum. He didn’t speak Aramaic or reference string theory; he doesn’t know those. Gibson obviously has some dark thoughts about Jews rattling around in his brain. In vino veritas? Perhaps. We don’t know what he says in private when he’s sober. Fortunately for him and for filmgoers, Gibson seems to have managed to keep it together since then.

It’s also possible that Gibson stifles hate speech when he’s not residing at the bottom of a bottle and that Ye knows better than to indulge his inner self-hating white nationalist when he’s not in thrall to a manic episode or depression triggered by a messy public divorce. Intriguingly, were he feeling sane, Ye might not even believe that garbage, much less express it. Some studies have established a link between extreme racism and bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other psychotic disorders.

Arguing in New York magazine that sanctions against Ye are appropriate if for no other reason than they serve as deterrents, Eric Levitz writes that “I don’t think we can actually know that West’s bigotry has nothing to do with his illness.” Just so. We don’t know. We can’t know. And that should be the determining factor. One of the core principles of Western culture is that the burden of proof rests with the accuser. If you don’t know for sure, you can’t convict.

Also, if deterrence worked on crazy people, Ye would have altered his behavior the first time he lost a business deal.

It is worth remembering that the Americans with Disabilities Act protects workers suffering from mental illness from getting fired. Ye wasn’t an employee of the companies that stopped working with him, so the law doesn’t apply. Nevertheless, corporate America should voluntarily stand for the principle that psychological problems should not be cause for terminating a contract. Businesses that are understandably shocked and disgusted by Ye’s crazy antisemitism—anti-Semitic craziness?—might instead have issued statements that deplored the sentiments, expressed concern for Ye’s mental well-being, and paused rather than severed their relationships until he seeks and receives the help that he needs.

Hate speech like antisemitism is inherently insane. When the person speaking is off-kilter, a purely political response misses the point even if that hatred has a political tint.

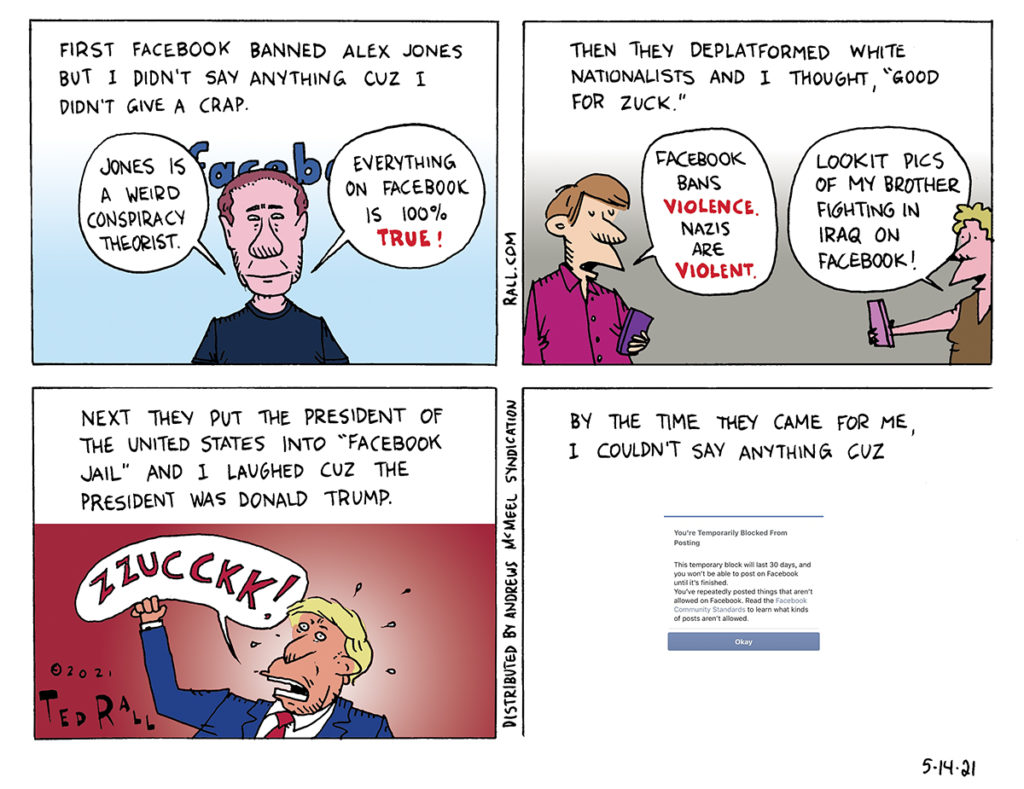

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)