One year ago, America lost yet another war. Afghanistan is right back where it was two decades ago, under control of the Taliban. The question is: what, if anything, have we learned?

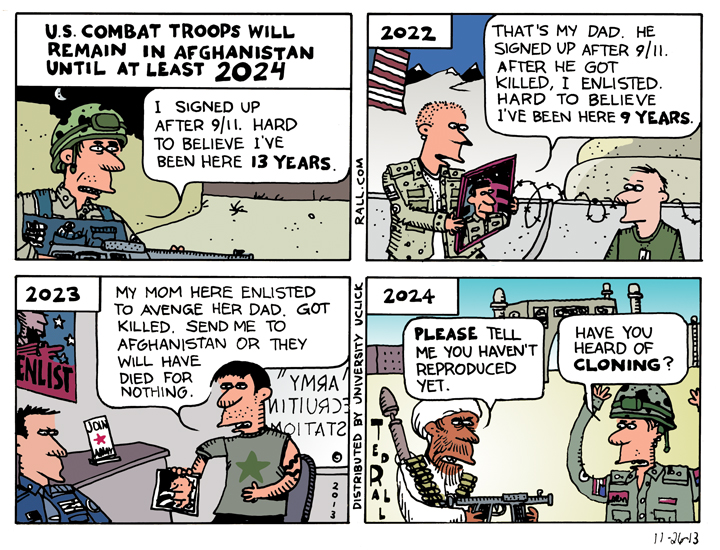

Make any mistake you like, but don’t make the same mistake twice—or four times. The U.S. committed the same errors of omission and commission in Vietnam, and then Iraq; our failure to draw intelligent conclusions from those conflicts and apply them going forward led us to squander thousands of more lives and billions of more dollars in Afghanistan. Here we go again: unless we learn from our decision to go to war against Afghanistan and then occupy it, we are doomed to our next debacle.

Afghanistan Lesson #1: When politicians tell you that war is necessary and justified, always be skeptical.

President George W. Bush told us that we had to invade Afghanistan in order to bring Osama bin Laden to justice for 9/11. Almost certainly false; the guy was probably in Pakistan. And if bin Laden was in Afghanistan, Bush could have instead accepted the Taliban’s repeated offers to extradite the accused terrorist. Bush argued the war was necessary to take out four training camps allegedly used by Al Qaeda. But Bill Clinton bombed six such camps using cruise missiles in 1998, no war required.

Bush’s casus belli for Afghanistan made no more sense than his evidence-free weapons of mass destruction in Iraq or the fictional Tonkin Gulf incident LBJ used to get us into Vietnam. It’s long overdue for American voters to download and install a sturdy BS detector about wars, particularly those on the other side of the planet.

Lesson #2: Never install a puppet government.

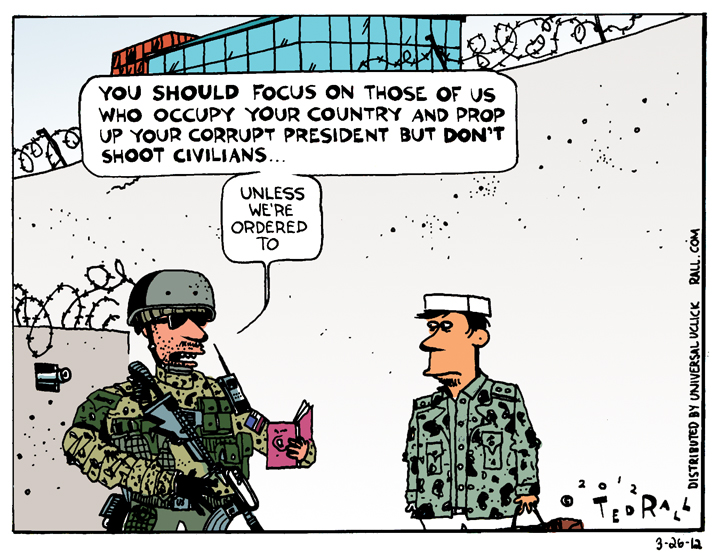

Of the countless mistakes the U.S. made in Vietnam, no single screwup led to more contempt for the United States than its sustained support for the deeply unpopular, brutal, autocratic president of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem. Saddam Hussein looked positively brilliant in comparison to the exiled con man, Ahmed Chalabi, whom Bush tried to replace him with. Rather than allow Afghans at the post-invasion loya jirga council meeting to choose their own ruler, like the long-exiled king, the U.S. pulled strings behind the scenes by buying the votes of corrupt warlords in support of the dapper Hamid Karzai, who had little popular support. Three years later, even the establishment New Yorker conceded that “if American troops weren’t there, Karzai almost certainly wouldn’t be, either.”

The U.S. propped up Karzai and his successor and close ally Ashraf Ghani for 17 more years.

Lesson #3: Never try to exclude an entire political party or group from a nation’s political life.

The Taliban’s base of power was the ethnic Pashtuns who comprised 40% of Afghanistan’s population. Yet the Taliban were not permitted to attend the loya jirga. They could not run in parliamentary elections under the U.S.-backed puppet government. Marginalized and “alienated from the central government, which they believe[d was] unfairly influenced by non-Pashtun leaders and interests,” in the words of a prescient 2009 Carnegie Endowment white paper, they had two options: stand down and shut up, or resort to guerilla warfare.

The U.S. messed up the same way in Vietnam and Iraq. In U.S.-backed South Vietnam, communists and their nationalist allies were excluded from electoral politics. Iraq’s Sunnis, 32% of the nation, lost their leader when Saddam was overthrown by U.S. forces, got fired from the military and other jobs by Bush’s idiotic deBaathification policy and humiliated by America’s new darlings, Shia politicians and their factions—sparking a bloody civil war and leading to U.S. defeat.

Lesson #4: Never be a sore loser.

European powers that offered financial assistance and training to their former colonies after independence in places like Africa continued to enjoy influence within those countries. Examples include the UK’s relationship with India and France’s role in Mali, Senegal, the Central African Republic and even Algeria, which cast off the French yoke after an eight-year-long struggle famously characterized by torture and terrorism.

The United States should try something similar when it loses its wars of aggression: lick its wounds, acknowledge its mistakes and offer to help clean up the messes it makes when it withdraws from a country strewn with mines and cluster bombs.

It took 20 years before the U.S. reengaged with Vietnam after the fall of Saigon—two decades of squandered rapprochement and lost international trade. This occurred despite the precedent of World War II, in which U.S. occupation authorities worked to insinuate themselves with their defeated enemies Germany and Japan almost on day one, two relationships that paid off for all concerned.

Its nose bloodied by its debacle in Iraq, the U.S. has allowed Iran to become the dominant outside power inside the country.

And now the U.S. is doing the same thing in Afghanistan as in Iraq—nothing. Afghans are gaunt and hungry because of drought and the U.S. decision to cut off aid and frozen Afghan government funds. The economy is collapsing. The enormous U.S. embassy in Kabul is closed, making it impossible for Afghans to contact the U.S. government.

All that investment of money and time, and who will get the more than $1 trillion in untapped natural resources, including copper, lithium, and rare-earth elements? China, most likely. If the U.S. could get over itself, it might salvage some influence over the new Taliban government in Kabul and open new markets. Let girls go to school and women work, President Biden could tell them, and we’ll release some funds. Arrest and hand over figures like the recently droned Ayman al-Zawahiri, who was living in Kabul, and we’ll restore aid. Carry out more reforms and we’ll establish diplomatic ties.

Picking up your toys and going back to your house after losing a fight might feel good. But it’s immature and counterproductive in a world in which success depends on having friends and collaborators.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)