Coupla weeks ago, I speculated that we may soon witness the end of the Democratic Party as we know it. I was kind. I didn’t mention the fact that the party is all out of national leaders. I mean, can you name a likely, viable Democratic candidate for president in 2020? Can you name three?

I followed up with more crystal-balling in a piece predicting that the meek will not inherit the earth if and when Trump gets dragged out of 1600 Penn by Senatorial impeachment police. The meek — the Democrats — could have/should have been the Anti-Trump Party. But they’ve dropped the ball. After the deluge, Paul Ryan.

With everyone so focused on the Trump Administration dead pool — how will he go? when? — we’re overlooking that Republicans could come out of the Trump debacle stronger than they went in. How crazy is that?

Now I want to look at another facet of this political Rubik’s cube: what the Democrats could do to avoid political irrelevance.

- Democrats should stop calling themselves “The Resistance.” It’s an insult to the actual resistance fighters of World War II who were tortured and murdered. It’s also an attack on Strunk and White’s diktat not to stretch words beyond their plain meaning. Resistance to Republicans hasn’t been part of Democratic politics for generations. Quit the hype. Under-promise, over-deliver.

- Democrats should actually resist Trump and the Republicans. They shouldn’t have gone along with any of his nominees, but their promise to filibuster pencil-necked right-wing libertarian freak Neil Gorsuch would be a nice place to start. No Democrat, including those from purple/swing states, should vote for any GOP nominee or legislative initiative. Let’s not hear any more stupid talk of finding “common ground” with Trump on infrastructure spending or anything else. The GOP controls all three branches of the federal government so they’ll get whatever they want — and they should own whatever happens as a result. Democrats shouldn’t get their hands dirty.

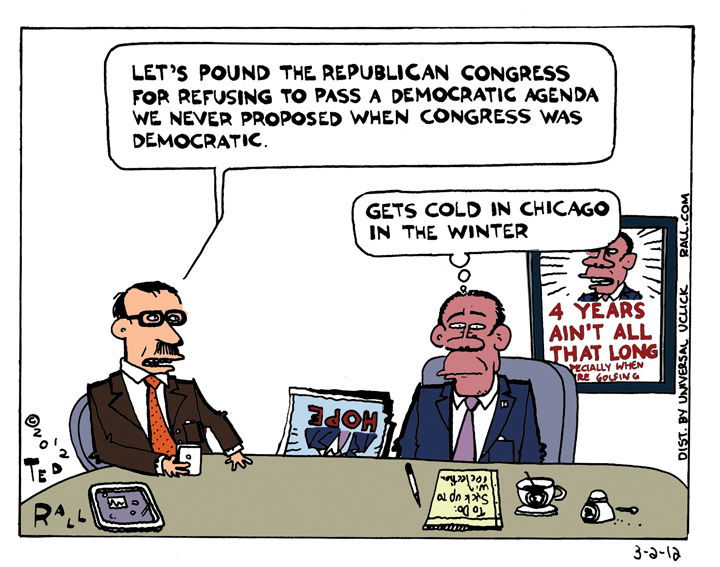

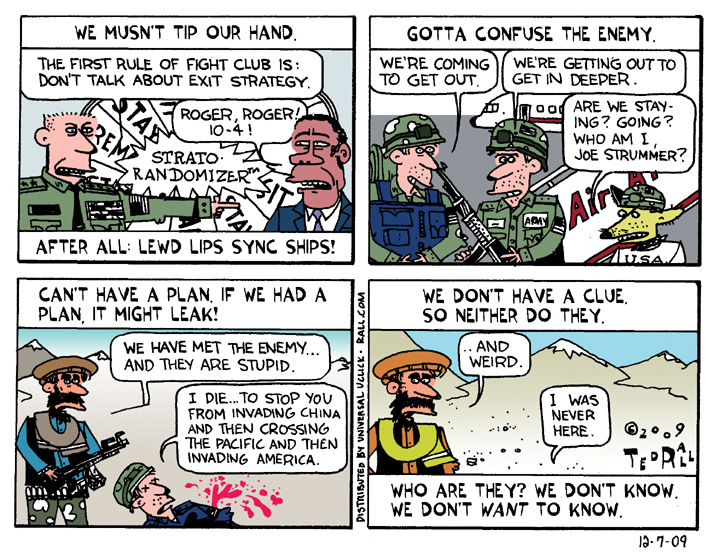

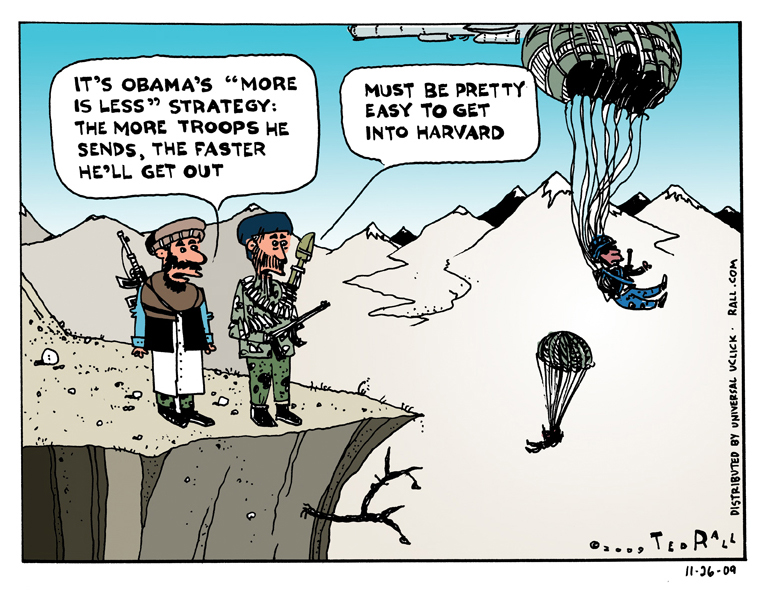

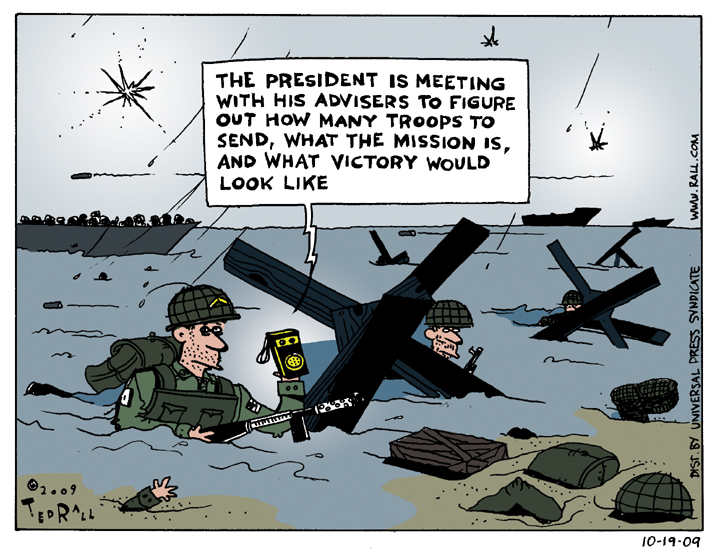

- Democrats ought to articulate an alternative vision of what America would look like if they were in charge instead of Trump and the Republicans. It’s nice (not least for the 24 million people who would’ve wound up uninsured) that the repeal and replacement of Obamacare imploded. But that victory goes to rebellious Republicans, not Democrats. Here was a national debate over the ACA — Obama’s signature achievement — and Democrats didn’t even participate! How crazy is that? Never mind that they wouldn’t have gotten a vote on it — Democrats should have proposed their own bill reforming the ACA, one that moves left by adding single payer. Every Republican idea should be countered by an equal and opposite Democratic idea. Other countries call this act of self-definition shadow governance or, in a time of war perhaps loyal opposition. Whatever you call it, refusing to let your adversaries frame the acceptable ideological range of political debate is basic. In other words, a standard party-out-of-power tactic (e.g., the Tea Party 2009-2016).

- Democrats need to stop disappearing between elections. Campaigns are exhausting and it’s natural to want to catch one’s breath and conduct a postmortem to determine what went well and wrong. But it’s gotten to the point that the only time left-of-center voters hear from the Democratic Party is the year of a major election, for the most part only a few months before November and then only to ask for money. In the era of the 24-7 news cycle and the Internet, that hoary see-you-in-two-to-four-years approach is as outmoded as Bernie Sanders’ and Hillary Clinton’s cut-and-paste stump speeches and network TV shows that take summers off for something called “vacation.” A modern party should become part of our everyday lives. Every burg needs a Democratic Party storefront bustling with activity. Every Republican officeholder needs a ferocious Democratic challenger, even at the localest of local levels. Door-to-door campaigning and grassroots organizing should happen every day of every month of every year — in every state, regardless of presidential race electoral vote considerations, just like Howard Dean said.

- Bernie Sanders says Democrats can and should do class issues and identity politics. He’s right. As we’ve seen with the increased acceptance of LGBTQ people in recent years, the two are intertwined: gays’ incomes have risen But here’s the rub: you can’t really take on poverty and income disparity while accepting contributions from banks and other corporations whose interest lies in perpetuating economic misery by keeping wages low. The biggest lesson Dems should internalize from Bernie’s candidacy is his reliance on small individual donations.

(Ted Rall is author of “Trump: A Graphic Biography,” an examination of the life of the Republican presidential nominee in comics form. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)