An investigation by Los Angeles Times reporters found that the “LAPD misclassified nearly 1,200 violent crimes during a one-year span ending in September 2013, including hundreds of stabbings, beatings and robberies.”

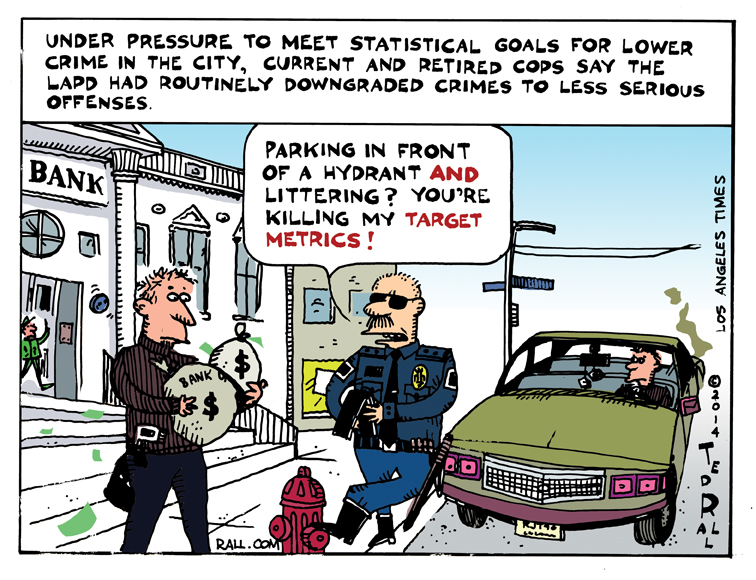

Like all police departments, the LAPD strives to reduce crime. The trouble is, it looks like the numerical targets are having an unintended result. Rather than actually reducing crime — perhaps an unrealistic goal given that the economy has been significantly less than stellar for the last six years — there’s substantial evidence that cops are gaming the system by painting a rosier picture than what’s really going on on the streets.

Retired and current LAPD officers complain that the department is encouraging cops to underreport crime and reduce the seriousness of charges in order to meet statistical goals for lower crime: “The incidents were recorded as minor offenses and as a result did not appear in the LAPD’s published statistics on serious crime that officials and the public use to judge the department’s performance,” wrote Ben Poston and Joel Rubin.

Interestingly, the alleged misconduct did not occur across the entire horizon of criminality: “Nearly all the misclassified crimes were actually aggravated assaults. If those incidents had been recorded correctly, the total aggravated assaults for the 12-month period would have been almost 14% higher than the official figure, The Times found.” The effect was nevertheless significant: “The tally for violent crime overall would have been nearly 7% higher.”

The LAPD’s top-down target metrics approach is familiar to anyone who has worked for a major corporation in recent years. Do more with less resources, the directive goes, or else. Most of the time, of course, workers do less with less. Which may what happened here.

Like other government agencies, the police have suffered budget cuts that have hurt the ability of cops to do their jobs. Low starting salaries have made it difficult for the department to recruit new officers. With job growth in the “recovery” puttering along at 1.6% annual growth, long-term unemployment — either an indicator or a cause of crime, depending who you ask — remains high in the Southland.

For cops, it adds up to an impossible situation: harder job, less ability to do it, top brass in thrall to number crunchers insistent that what cops need is the pressure of higher standards. If some members of the force are cheating, you might be able to blame them — but you can’t be surprised.

It reminds me of the teaching test scandals, when California teachers helped their students cheat on the Academic Performance Index scores. It ain’t right. But neither is making impossible demands.